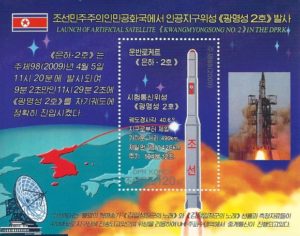

Postage stamps commemorating the “successful” delivery into orbit of North Korea’s two satellites, Kwangmyongsong-1 (1998) and Kwangmyongsong-2 (2009) Postage stamps commemorating the “successful” delivery into orbit of North Korea’s two satellites, Kwangmyongsong-1 (1998) and Kwangmyongsong-2 (2009) |

Nearly five months have passed since I last evaluated the situation in North Korea, making predictions and recommendations on how the United States should proceed with the nascent “Kim 3.0.” All those months ago, I argued that it would be a mistake to continue negotiations with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) until the political dust had settled—to give Kim Jong-Un time to consolidate his power. I was shocked when I read the announcement that not only had the United States resumed talks so soon after Kim Jong-Il’s death but had also come to an agreement with the DPRK to suspend long-range missile launches, nuclear tests, and nuclear activities at Yongbyon. As I was preparing a mea culpa post, the DPRK declared that it would be launching a weather satellite into space in celebration of Dear Leader’s 100th birthday; code for testing an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (a system capable of delivering a nuclear warhead to the west coast of the United States). Of course, this was followed by blustering on either side and the launch eventually failed. Much has been said and written about the events of the last few months, but I would like to focus on the role China will play in future U.S.-DPRK relations.

Between a Rock and a….

As South Korea has moved away from its Sunshine policy, the DPRK has become more and more dependent on China to support its feeble economy. If it so desired, China could put enough pressure on North Korea to convince it to drop its weapons program. However, as experts recently testified at a House Committee on Foreign Affairs hearing, China walks a tenuous rope between preventing a fully nuclear capable North Korea from emerging and forestalling the implosion/explosion of the Kim Regime. From China’s past behavior, it is clear that China prioritizes maintaining the stability of the Kim regime.

There are a number of reasons why regime-collapse in North Korea is an undesirable outcome for China. First, the DPRK plays a strategic role as a buffer state both to U.S. military presence in the region and Russian neighbors to the North. Historically, China has questioned American strategy in the region and even suspected that U.S. activities on the Korean peninsula are an excuse to maintain a military presence in the event that China decides to aggressively reunify Taiwan with the mainland.

Second, China would face an enormous influx of refugees if the Kim regime were to destabilize or fall apart entirely. Even when not facing massive famine, it is estimated that 5,000 North Koreans cross the border every year to escape starvation. If the Kim regime were to collapse, China would be subject to unprecedented mass migration in an area that is already saturated with ethnic Koreans. A mass migration would make it difficult for Chinese officials to control movements along the border and to distinguish refugees from residents of China. Evolving domestic politics in South Korea could also exacerbate the refugee problem as recent polling and aid programs indicate that South Koreans are dubious at the possibility of reunification with their Northern brethren. If this scenario were to play out, China would face extreme difficulties coordinating the handling of refugees.

If a conflict were to emerge out of a DPRK regime collapse, China, for all its might, is unprepared for a crisis situation. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has not been subject to significant combat since the invasion of Vietnam in 1979—an unmitigated disaster. The chain of command is also complicated; the PLA is not a part of the state apparatus but is instead responsible to the communist party and is run by their Central Military Commission, not the Ministry of Defense. If there was disagreement between top-leadership of the Chinese government and the members of the Central Military Commission over policy, it could lead to a break-down in response to any humanitarian or other security emergency. Finally, corruption is rampant in the PLA, to such an extent that it has caused the development of a “fragmented and stove-piped structure of the overall crisis decision making process.” This is a fundamental problem that touches all points of Chinese Foreign Policy, not just the possibility of dealing with the potential collapse of the Kim regime.

Conclusions for Future U.S.-DPRK Relations

By relying on a negotiating partner and interlocutor with objectives that diverge so greatly from our own, the United States has laid a weak diplomatic foundation. Yet, there is some strategic space where the United States and China have common ground.** China does not want a full-fledged North Korean Nuclear power, as this would likely cause South Korea, Japan, and perhaps even Taiwan to pursue similar weapons programs. Therefore, the United States ought to establish an official line of communication with China to prevent miscommunications and coordinate during times of crisis, while, at the same time, move away from the expectation that China will solve the North Korean problem to our satisfaction.

It is time for the United States to re-evaluate its objectives for relations with the DPRK. Patrick Cronin and Scott Snyder recently testified that it is unreasonable to expect to achieve the maximalist goal of a non-nuclear North Korea and that United States should look to its allies South Korea and Japan. I agree that such maximalist goals are unrealistic, but I do not believe that South Korea is willing to gamble the status-quo when losing the game would be unacceptably costly (possible nuclear war, economic decimation in a reunification process).

Instead, the United States needs to take ownership of its own goals and declarations.

Most recently, American leadership stated that a North Korean missile launch was unacceptable, but neither cited nor executed any repercussions. After the sinking of the Cheonan in 2010, President Obama claimed that the United States would not negotiate with North Korea unless they made a demonstration of their dedication to de-nuclearization; soon thereafter American diplomats returned to the table. If we do not create, pursue, and take ownership of consistent set of policy objectives and follow up provocative actions with repercussions, the United States will continue to fail in its dealings with North Korea.

**After finishing this post, Secretary Leon Panetta testified before the U.S. House Armed Services Committee, confirming that to some degree China has been assisting North Korea with the development of their missile weapons systems. Due to the “sensitivity” of the information, Secretary Panetta did not elaborate on the extent to which the U.S. Government believes China is assisting the DPRK with these programs. Without more information, it is difficult to determine how much common ground remains between the United States and China when dealing with North Korea.