The acquittal of Ngudjolo calls into question the effectiveness of the ICC, especially the Office of the Prosecutor, to remain a system of international criminal justice

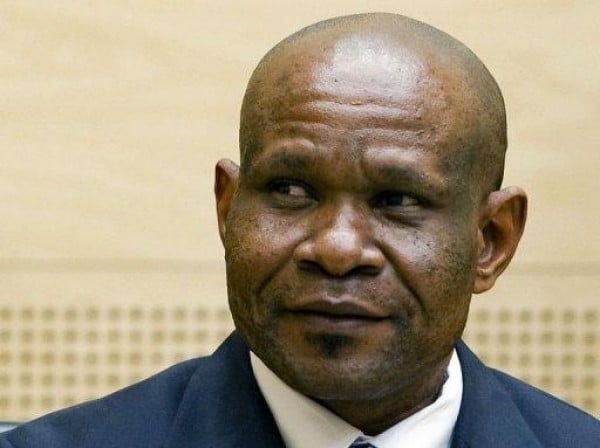

Yesterday in The Hague, the International Criminal Court (ICC) acquitted former Congolese Warlord Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui of all charges, including crimes against humanity and war crimes, in connection with the massacre that occurred in 2003, in the town of Bogoro.

Ngudjolo was on trial for a host of crimes including rape, pillaging, murder, forced enslavement and utilizing child soldiers. He was arrested in 2008 and pleaded not guilty to all charges, claiming he learned about the attack days later. He has also denied being a part of any militia group.

The attack on Bogoro was part of the conflict that broke out during the second Congolese War in the Ituri province between 1999-2003, among two ethnic groups that populate the region, the Lendu and Hema. Bogoro village was a strategic town, which is located just 25 kilometers south of the main hub of Bunia in the mineral-rich Ituri Province. Mr. Ngudjolo and fellow Lendu militia leader, Germain “Simba” Katanga, were accused of ordering the attack on Bogoro, a village composed mostly of Hemas. Katanga is still on trial for these crimes and a verdict is expected in early 2013. The brutality of the attack has come to light as many witnesses testified that people were burned alive, women were raped and babies were smashed against walls.

The court stressed that the ruling does not mean that no crimes were committed in Bogoro “nor does it question what the people of this community have suffered on that day”, but that it was difficult to establish Ngudjol0’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt because the testimony was “too hazy and contradictory”.

This ruling strikes another massive blow to the ICC who finally sentenced its first defendant earlier this year, Thomas Dyilo Lubanga, in July. Ironically, Lubanga is an ethnic Hema and was on the other side of the conflict from Katanaga and Ngudjola.

The ICC opened its doors in 2002 and has been marred with more failures and shortcomings than successes, something made even clearer with yesterday’s verdict. With an annual budget of approximately $140 million and a total cost since inception eclipsing $900 million, the fact that only one successful trial has been completed further damages the court’s reeling reputation.

In addition, many of the criticisms against the ICC range from slow prosecutions to “Africa bias”, as all 24 people indicted, awaiting trial, convicted or acquitted are from Africa. Now, ineffective cases established by the prosecution can be added to those criticisms.

It may be that Ngudjolo is not guilty of the massacre in Bogoro, but the unsuccessful case presented by the Office of the Prosecutor has severely damaged the trust that participating nations have placed in the court. Since it was established by the panel of judges that Ngudjolo was a militia leader following the massacre, but it was unclear if he was a leader at the time of the massacre, then they could not prove that he ordered the killings beyond a reasonable doubt. However, as was argued by Human Rights Watch Senior DRC Researcher, Anneke Van Woudenberg, there were numerous attacks of this magnitude by all sides in the Ituri conflict, therefore the prosecution should have broadened its case against Ngudjolo and Katanga to include other international criminal acts as well, thus strengthening the case. Just to reinforce this point, the judges also emphasized that this verdict did not mean that Ngudjolo was innocent of all atrocities during the fighting.

Due to such gross mismanagement of cases, it is no wonder that Libya refuses to hand over Saif Gaddafi, preferring to try him at home. The court’s mandate under the Rome Statute of 1998 includes a clause under Article 17.1(b), which is the principle of subsidiarity, which states that the ICC is only supposed to try alleged criminals if the State is unwilling or unable to carry out such proceedings. A verdict such as this may give member states more pause to try their war criminals at home, instead of dealing with the lengthy and costly procedures in The Hague, which may produce little to no results.

Last week the ICC’s Chief Prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, called for the arrest of Joseph Kony and the other leaders of the Lord’s Resistance Army, a rebel group that has been operating across Central African since 1986. “It is a long time since we issued arrest warrants. I think it’s time Kony is stopped, arrested and brought to the ICC.” She also emphasized the fact that the ICC did not maintain a police force and therefore it was up to the member states to arrest fugitives. There are currently 12 indicted fugitives for the ICC. Issuing such statements in light of the recent verdict opens the prosecutor to more criticism, as she is demanding that forces arrest and turn over the evasive Kony, while her office has failed to produce many successful results. Kony is currently being pursued by a coalition of African Union forces from Uganda, South Sudan and Central African Republic, along with 100 U.S. troops in an advisory capacity.

With the results of this trial, the ICC has once again damaged the trust bestowed by member states more than a decade ago. By compiling a case that proved narrow and ineffective for the victims of the massacre in Bogoro, the ability of the court to carry out its mandate effectively and efficiently is once again called into question. This may lead to less and less member support, which is crucial to the success of the ICC. In the end, without a better management of trials, evidence, cases and inevitably justice, the ICC might eventually be chalked up as a failed experiment by the international community. More setbacks such a yesterday’s may draw conclusions that the court is an ineffective system of international criminal justice. How long can the vast budget be doled out to the court without any tangible results? Hopefully this is a lesson to the adolescent prosecutor and her office that changes need to be made to ensure the continuance and success of the court in carrying out its mandate.