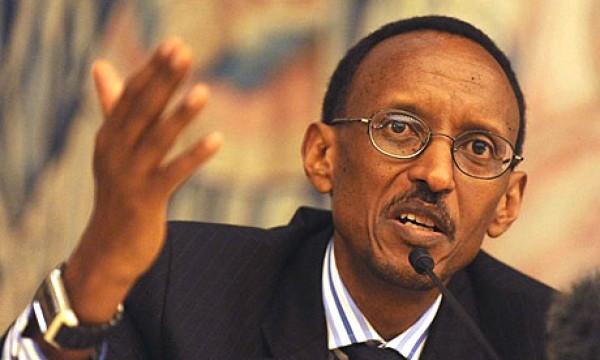

In order for a sustainable peace deal to be achieved in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the grievances between the Hutus and the Paul Kagame-led Tutsis must be solved.

As peace talks commenced almost a week ago in Kampala, Uganda, the prospects of a lasting agreement between the rebel group M23 and the central government in Kinshasa seemed more of a ‘pipe dream’ then an actuality. The Democratic Republic of Congo has been down this road a multitude of times in the last 15 years with little tangible results.

When the Second Congolese War supposedly ended with a ceasefire agreement in Lusaka, new violence began almost immediately. A series of talks among the aggregation began again in 2001, after the assassination of former President Laurent Kabila, but none of them produced any results either. Finally, in 2002, another deal was struck between Rwanda and the DRC, and followed by a 2003 agreement between the DRC, Uganda and the Uganda-backed rebel group, Movement for the Liberation of the Congo (MLC). This agreement established the steps to forming a new central government and supposedly laid the groundwork for long-term and sustainable development under an umbrella of cooperation.

Then in 2006, after the government in Kinshasa failed to live up to their part of the agreement and disarm and neutralize former Rwandan Hutu rebels operating in the country since 1996, named the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) — which is comprised mainly of Hutus that participated in the April 1994 Genocide in Rwanda — a Rwandan-backed Tutsi rebel group emerged again under the French acronym CNDP, or the National Congress for the Defense of the People, led by Tutsi General Laurent Nkunda.

It took until 2008 and nearly 400,000 Eastern Congolese residents displaced for another peace deal to be struck between the rebel group and the government. Unfortunately, once again this peace deal fell apart. Eventually Nkunda was betrayed by his Kigali backers and ousted as head of the group after he refused to integrate into the Congolese Army. International Criminal Court (ICC) fugitive Bosco Ntaganda seized control of the group and a new agreement was signed on March 23, 2009. The soldiers from CNDP were integrated into the Congolese army as part of the agreement and a sustainable peace deal seemed once again at hand.

Fast forward to April of this year when many of the former soldiers and leaders of CNDP — mainly followers of Ntaganda — mutinied from the Congolese government to form M23, a name derived from claims that the central DRC government reneged on their promises of the March 23, 2009 agreement.

So why do these peace accords constantly fail?

In order to understand the series collapses in peace agreements, the foundations of the war in the Congo must be explored. Originally the violence in the Congo commenced as a continuance of the Civil War in Rwanda. In April of 1994, one of the worst genocides in modern history occurred as 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were slaughtered by Hutu radical militias and Hutu government troops. Upon hearing of these atrocities General Paul Kagame – the current president and leader of the Tutsis in Rwanda — led a coalition of troops from neighboring Uganda to oust the Hutu government and seize control of the country. More than one million Hutu refugees, fearing reprisal from the new Tutsi-government, fled over the border into neighboring Zaire (now the DRC). Only about 50,000 of these refugees were members of the militia groups that carried out the Genocide.

Since that time a series of proxy wars between Rwandan Tutsis and Hutu militia rebels have been a near constant in the eastern provinces of the DRC, namely North and South Kivu. The DRC government has been guilty of posturing between both sides. However, in nearly every instance of reoccurring violence that fractured a peace deal or a ceasefire, either Tutsi or Hutu rebel groups have been responsible. Even today the two main rebel groups operating in the eastern provinces emanate from the Rwandan Civil War, with the M23 rebel group comprised of mostly Rwandan and Congolese Tutsis and backed by the Rwandan Tutsi regime, and the FDLR, which is composed of former Rwandan Hutu militia members, many of which are responsible for the 1994 Genocide.

The war in the Congo began in 1996-97 when Rwanda invaded Eastern Congo in an attempt to eliminate the lingering remnants of the Hutu militia members. Since that time there has been an ongoing battle between the Hutus and Tutsis in Eastern Congo in an attempt to prolong a Civil War that supposedly ended nearly two decades ago. All of this fighting has cost the inhabitants in the eastern provinces their homes, their lives and their way of life. Leaders from both ethnic groups in these proxy wars have been accused of massive war crimes and crimes against humanity and indicted by the ICC, as the civilians are often the target of malicious attacks by both sides.

Genocide is a very difficult thing to forgive, and the emotions derived from the horrific events of 1994 will never be fully repaired or extinguished. However, the continuance of this seemingly endless war that has arisen from the hatred between two neighboring ethnic groups has only hurt more civilians through constant murders, rapes and pillaging. The only way to end this continual pattern of violence in Eastern Congo is to force these groups to settle their differences, or disarm all sides. No lasting solution in the Congo can be realized until this age-old hatred is dealt with. Though the failures of the international community in Central Africa have been well documented, it is time for world leaders to intervene with forced negotiations or watch the pattern of perpetual conflict continue.