Source: The Examiner

Since in the summer of 2010, Admiral Mike Mullen, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff at that time, has argued that the national debt constitutes “the most significant threat to our national security.” As he elaborated, it became clear that his real concern was the strength of the U.S. economy, the basis for sustaining military power. “That’s why it’s so important that the economy move in the right direction, because the strength and the support and the resources that our military uses are directly related to the health of our economy over time.” An indisputable point, we can add to it that the economy also supports many other aspects of foreign policy, including such intangibles as national image and reputation. The debt is a threat to the extent that it undermines the economy.

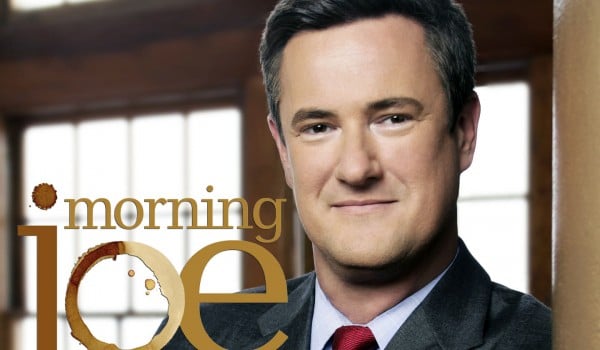

Joe Scarborough, a former Republican representative from Florida who now writes a column for Politico and hosts Morning Joe, a news and opinion show on MSNBC, cites Mullen’s concern as part of his ongoing debate with Paul Krugman over the need to reduce the federal deficit immediately. Now for any talk show host to debate Paul Krugman on macroeconomics is an ambitious undertaking. Krugman has a Ph.D. in the subject, is a Princeton professor, and has been awarded the Nobel Prize in economics. Scarborough’s main qualification, on the other hand, is that he is a person with strong opinions. That said, he is far from the most closed-minded person on TV. He has aired differences with his party on such touchstone issues as gun control and taxes, and his show features regular and semiregular guests who disagree with him, even if he sometimes finds it difficult to resist the urge to cut them off. Even his views on deficits may not be as unsophisticated as sometimes depicted.

Their debate has received considerable attention, perhaps more than it deserves. For the sake of full disclosure, let me note that I lean toward Krugman’s side, but I do not propose to jump directly into their argument, trying to refute anyone’s position point by point. Rather, I would like to adjust the framework a bit, in a way that I think will make the indirect and counterintuitive aspects of the situation clearer to the casual observer.

First, let me highlight that many people approach the question of deficits in too direct a fashion — i.e., deficits are high, high deficits are a problem, ergo spending must be cut. Economics, however, is not a realm of simple, direct cause-and-effect relationships, but rather a realm of synergistic interactions that can generate counterintuitive outcomes. In a classic example, a large number of competitive firms seeking to maximize profits can lead to reduced prices for all as they attempt to attract customers away from one another.

Second, it is important to remember that the economy is the issue, not the deficits per se. Deficits are a threat to the economy, but they are neither the only threat nor the most immediate threat. The most immediate threats are slow growth and unemployment, which in addition to being problems in their own right also undermine the economy’s capacity to reduce deficits or pay the debt. Moreover, measures aimed at the immediate threats can actually improve the deficit situation, while measures directly addressing deficits can make the immediate threats worse and may not even help the deficit.

Third, the absolute amount of the deficit (even if it is a genuinely big, scary number) is less important than the debt-to-GDP ratio. The gross domestic product (GDP)—the measure of a country’s overall economic output—is an indication of that country’s ability to sustain or pay off its debt. To use a rough analogy, a credit card debt of, say, $150,000 would represent a fiscal crisis for me, but it would be pocket change for Bill Gates. The size of the debt is meaningless in isolation from the capacity to make the payments.

Fourth, following on the importance of the debt-to-GDP ratio, deficits should not be addressed in isolation from the current state of the economy. Austerity in a downturn is counterproductive. By further reducing demand, it will exacerbate the real and current crisis—unemployment—in the name of addressing the eventual, potential crisis—debt—and may not eliminate the deficit in any case. The United Kingdom has engaged in austerity since mid-2010. As a consequence, it recently entered the third stage of a triple-dip recession, while the United States has sustained growth, albeit at a modest rate. The International Monetary Fund, in a reversal of its previous interpretation of the multiplier effect in austerity, recently concluded that every $1.00 saved through budget cuts in Europe may have reduced economic activity by as much as $1.70, generating a downward spiral. The British economy has contracted so much that, despite some success in reducing deficits, the debt-to-GDP ratio has actually gotten worse. Even though the austerity policy was sold as a means to instill confidence in markets, Moody’s downgraded British debt this past Friday, citing the country’s rising debt burden and tepid growth outlook. Moody’s anticipates that the debt burden will continue to worsen until 2016. In the United States, on the other hand, the deficit this year, as a percentage of GDP, is expected to be half of what it was in 2009.

Fifth, deficits should not be addressed in isolation from the sources of the deficits. The current deficits were not caused by a sudden expansion of discretionary spending on new government programs. The stimulus act of 2009 represented a temporary boost in spending, not a structural source of deficits. By and large, the impact of the stimulus on current deficits has already passed. (Moreover, cuts and caps already enacted under the Budget Control Act of 2011 will reduce nondefense discretionary spending in the future, as a percentage of GDP, to the lowest level on record, the relevant record going back to 1962. Austerity, relative to U.S. policy in past recoveries, is already stalling the economy.) The true factors behind the deficit can be grouped into immediate causes generating today’s deficits and long-term causes threatening large deficits in the future.

The most important immediate causes are three: tax cuts, unfunded wars and the recession itself. First are the Bush tax cuts, which ended the budgetary surplus inherited from the Clinton administration. Federal income taxes since then have been among the lowest in about three generations (although they were lower for a while in the 1980s, another time of large deficits). Contrary to the Bush administration’s expectations, the tax cuts never produced an economic boom apart from a modest surge that lasted from 2005 to 2006; job creation from 2001 to 2007 (not even counting the crisis of 2008) was the lowest on record, lower than it is today. Indeed, despite commonly repeated rhetoric, a recent report by the Congressional Research Service shows that upper-income tax levels have had little or no impact one way or the other on economic performance. The cuts did, however, produce a structural budget deficit. The government has not generated sufficient revenues to cover its expenditures at any point since that time. This was partly offset by tax increases on upper incomes enacted in January 2013, but further increased revenues, perhaps at other income levels, may well be necessary when the economy can afford them.

The second source of deficits is unfunded war. The decision to go to war in Afghanistan and Iraq without seeking increased revenues to cover at least some of the costs was unusual to say the least. With U.S. forces withdrawn from Iraq and the effort in Afghanistan winding down, there should be ample opportunities in coming years for savings in the defense budget. This will require political leaders, however, to accept that defense spending in time of peace need not be as high as it was in time of war. Scattered pockets of terrorists do not require a defense effort comparable to the Cold War. There has been political resistance to this notion, however, and more can be expected.

Finally, the third immediate source of deficits is the recession itself. Millions of people thrown out of work, for example, are no longer paying income taxes, which reduces government revenues. Government payments for unemployment insurance, aid to state and local governments, and other emergency actions increase government expenditures. The result is a larger deficit until the economic situation corrects itself. Not only will this not be helped by cuts to discretionary spending, the resulting deficit is both anticipated and desirable. The deficit generates demand and thus helps sustain an economy hurt by the reduced demand resulting from the sudden rise in unemployment. Spending in areas with a high multiplier effect can even improve the deficit-to-GDP ratio by generating economic activity greater than the value of the original expenditure. In a recession caused by a financial crisis, such as the current one, demand is further reduced by the urge of justifiably nervous companies and individuals to reduce their own debts (that is, engage in “deleveraging”) rather than to spend their money on current consumption. Deleveraging is a rational response from the perspective of the individual, but it delays the recovery. The overall lack of aggregate demand makes companies reluctant to resume hiring and production for fear that they will not be able to sell the increased output. Eventually, those companies and individuals will reach a satisfactory level of debt and begin purchasing again. At that point, the economic recovery should accelerate, government revenues should rise, expenditures should fall, and the government should be able concern itself with its own deleveraging. For both the public sector and the private sector to engage in deleveraging at the same time, however, is counterproductive in the extreme.

All of that concerns the current deficit. The principal source of anticipated long-term deficits is the rising cost of health care. Alan S. Blinder, a former vice chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, has recently drawn attention to this. Some people (including Joe Scarborough) have misunderstood this as a problem of Medicare. That is confusing two different issues. The basic problem is the cost of health care, whether it is paid for with private or public funds. While there are certainly improvements that could be made to the administration of Medicare, Medicare is not the source of the cost problem. Indeed, traditional Medicare is the single most cost-effective health care system in the United States today. Any policy that moves people out of Medicare into any other existing system (say, by raising the eligibility age) will therefore cost society more overall. To resolve the government’s fiscal problems by foisting the costs back onto the shoulders of the elderly (and remember, Medicare was invented because the elderly could not afford the much lower costs of a half-century ago) is merely setting the country up for the next crisis.

The rational approach to the long-term deficit, therefore, is not to cut Medicare and then tell yourself that the issue has been resolved. The answer is to reduce the cost of Medicare indirectly, by reducing the cost of health care for everyone. The Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) has started down that road. It would have gone farther if the opposition had not demagogued every cost-reducing element (as they have tended to do with all deficit-reduction proposals). Still, the upward trend in the cost of health care has already slowed. Part of this may be due to a recession-induced fall in demand rather than to the ACA, but at this point the ACA is not even fully implemented yet. Will the ACA as currently configured be enough? Maybe not, we still do not know. But it makes a lot more sense to see how far it does go and then further address the costs of health care, if necessary, than to simply slash effective programs willy-nilly and create new problems for the future.

At the outset of this lengthy blog post, I promised to address indirect and counterintuitive aspects of the problem of American power. I certainly think I have accomplished the indirect and counterintuitive parts. I suppose a few people out there may dismiss an argument that sees Obamacare as the starting point on the road to sustaining the United States’ status as a superpower, but there you have it. A country cannot be a superpower without maintaining its economic potential, and despite the seeming incongruity of it, we cannot, through ill-timed austerity, impoverish ourselves into prosperity.

Note: For people not familiar with the terminology, a deficit is the amount by which expenditures exceed revenues. The spending not covered by revenues is covered by borrowing; thus, accumulating deficits add to debt. On the other hand, a surplus results when revenues exceed expenditures, as occurred in the late 1990s. Surplus funds can be used to pay off debt. Technically, the Great Recession ended in June 2009, when economic growth switched from negative to positive. The subsequent recovery, however, has been so weak that the term recession is often still used to describe it.