“Events, dear boy, events.” British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan’s response when asked what he most feared is one of the most popular quotes among foreign policy scholars. How and whether to respond to the ongoing violence in Syria is now the barometer of President Obama’s foreign policy posture. Is it isolationist or interventionist? The appointment of new senior foreign policy officials (Samantha Power as U.N. Ambassador and Susan Rice as National Security Advisor) provides new opportunity for change in the Obama administration’s foreign policy outlook.

MacMillan’s quote underscores how personalities and inherited circumstances drive presidential decision-making. Debates about U.S. foreign policy responses to a given global crisis begin with what is theoretically appropriate. But theory is tempered by historical context. The prospect of a U.S. intervention in Syria that may be morally responsible and practically achievable is matched by the political reality that the U.S. is recovering from a protracted war in Iraq that was costly, unpopular and has not yet proven to be a lasting success. U.S. decisions regarding Syria are not occurring in a vacuum, but in the shadow of its last war.

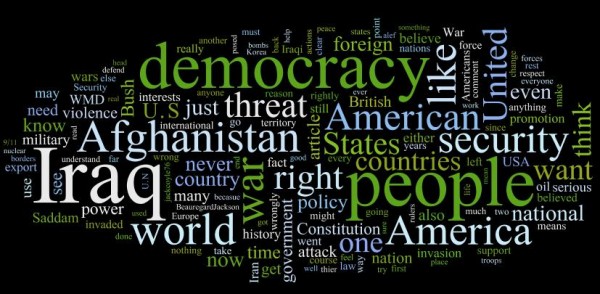

This dynamic was on display at a recent Brookings Institution conference on “Reviving U.S. Foreign Policy: The Case for Putting America’s House in Order.” Council on Foreign Relations President Richard Haass discussed his new book Foreign Policy Begins at Home with Brookings scholars Martin Indyk and Robert Kagan. The title of Haass’ book defines his emphasis on the risks inherent in U.S. interventions abroad. Alongside a primary focus on domestic affairs, the U.S. should be most concerned with influencing other countries’ actions abroad, not their internal affairs, Haass argues. It’s a popular argument following the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Even those who argue that the U.S. has historically been more interventionist than many believe (like Mr. Kagan) do not refute it fully. Our present political circumstances include the costs of our Iraq intervention and continued debates about the manner in which it was waged and whether it should have been waged at all. Questions also persist about what lasting outcomes are achievable in Afghanistan.

“Isolationist” and “interventionist” theories are not absolutes. They are separate ends of a continuum. MacMillan’s “events” are the best explanation of what pushes the foreign policy of the moment along the continuum. One questioner during the event’s Q&A period outlined a pertinent fact about U.S. interventions. Our actions in another country can set conditions that cause that country to develop a future foreign policy threat internally. Afghanistan is a prime example. After arming the Afghan rebels to counter a Soviet invasion, the U.S. retreated from the country at the end of the Cold War, our aims achieved and interests concluded. Over the following decade, the growth of the Taliban was on the U.S. policy radar but not seen as a present threat. Only after 9/11 – the most defining “event” since the end of the Cold War – did it become clear that a U.S. decision to disengage could have consequences as serious as engagement. The same questioner went on to point out that two of the most-cited U.S. foreign policy concerns – the proliferation of both extremist ideologies and nuclear weapons – are largely the product of internal developments in other countries. Iran’s development of a nuclear weapon is an example of an “event” in waiting that is driving policy now, and pushing the needle along the “isolationist/interventionist” continuum.

It’s hard not to conclude that, as much as theory is a guide when time allows, that foreign policy develops as a series of responses to events, many unforeseen. The Syria conflict may have only “least bad” outcomes. This event’s overarching message, however, was timely. U.S. engagements and disengagements with the world can pose equivalent threats, and the footprints they leave behind can grow with time.