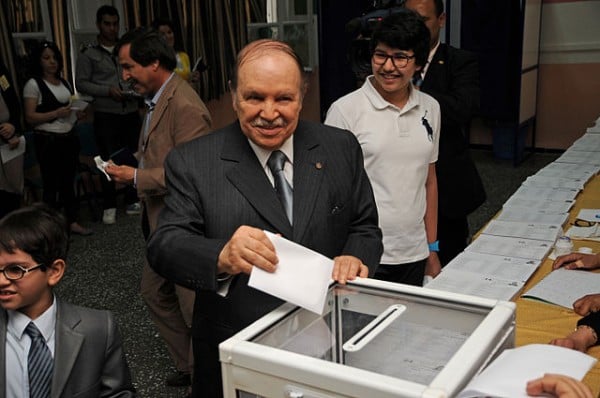

Abdelaziz Bouteflika was virtually absent from the proxy presidential campaign run by his prime minister. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Algeria just re-elected its longest-serving president for a fourth term, in what many describe as a fraught campaign punctuated by violence and citizen apathy. While the April 17 vote yielded no surprise, it unleashed a pertinent debate about the future of Algeria’s seemingly impermeable regime.

In an awkwardly short ceremony, Abdelaziz Bouteflika was sworn in on April 28. The infirm incumbent could hardly enunciate the presidential oath and limited himself to only a few sentences from a speech, the written copy of which was handed out at the ceremony.

Bouteflika’s fourth presidential bid was dogged by grave doubts about his debilitating health, deepening divisions inside the country’s obscure nomenclature and festering socio-economic ills. But above all, it highlighted the opaqueness of Algeria’s political system where someone as feeble as Bouteflika can run for the top post.

The returning candidate was virtually absent from the proxy campaign led by Prime Minister Abdelmalek Sellal, feeding speculation about who was behind his controversial decision to run.

Stability was the catchword of the campaign, with Bouteflika allies playing on memories of the Black Decade that claimed some 200,000 lives and displaced more. Bouteflika, who came to power in 1999, is widely credited for ending the bloodshed of the 1990s and orchestrating a peace treaty with Islamists. Former Prime Minister Ahmed Ouyahia described it as “a priceless achievement.”

Fears of a return to the civil war of the 1990s may trump Algerians’ desire for change and reaffirm the need for continuity embodied in Bouteflika’s candidacy. The violence enveloping the Arab Spring countries (from utter chaos in Libya to the attempted Islamist takeover in Mali and Tunisia’s lingering problems in the mountains) only serves to deepen those sentiments.

Conspiracy theories are rife in Algeria when it comes to the Arab Spring. Described as a plot to weaken and penetrate Arab states and sow fitna (chaos), the uncertainty resulting from political upheavals in the region serves as a cautionary tale.

While the premise of Bouteflika’s presidential campaign was that the ailing president remains indispensable for maintaining stability, the fractious reality points to the contrary – his irrelevance to the process where key decisions are taken elsewhere.

Some analysts point that the real reason for Bouteflika’s re-election bid is a failure to agree on a replacement and simmering tensions between the military and civilian poles of authority. According to this analysis, proponents of the fourth mandate are the ones who benefit most from Bouteflika’s inability to govern and wish to entrench the status quo to secure their interests.

Signs of divisions surfaced last year when the Secretary-General of the ruling National Liberation Front (FLN) openly criticized Algeria’s éminence grise, the head of the Intelligence and Security Department (DRS). Amar Saadani accused General Mohamed Mediene (known as “Toufik”) of “interfering in the work of the media, press, and political parties.” The public spat betrayed fractures within Algeria’s seemingly insular and cohesive polity.

Citizen reactions to the presidential contest varied from complete indifference to scoffs and bits of dark humor to anger crystallized in the nascent movement, named “Barakat” (“enough” in Algerian dialect).

Just two days after the elections, eleven soldiers deployed to provide security for the poll were slain, in an attack claimed by al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) on May 1. Periodic terror assaults on security forces and pockets of violence in the marginalized Kabylie region belie the government’s claims of reinstated stability.

But beneath that, there are deeper systemic challenges brewing with a potential to significantly destabilize the regime if left unaddressed. From the ethnic conflict between Arabs and Amazighs in Ghardaia to problems linked to housing and unemployment that routinely erupt into riots, Algeria faces an array of afflictions that require a structural and systemic overhaul. According to some estimates, the country witnesses over 10,000 riots annually. The specifically Algerian term of “hogra” (translated as “contempt”) captures the problematic nature of citizen-state relationship in the country. An overarching sentiment of disenfranchisement and disaffection with state authorities that plunged the country into widespread corruption after heroically won independence guides Algerians youth’s attitude to le pouvoir.

Though the regime had the wherewithal to keep the Arab Spring at bay, the economy’s over-dependence on hydrocarbons bodes ill for the future. Oil and gas constitute about 95% of exports but the sector only employs two percent while youth unemployment stands at 25 percent. Two-thirds of the population are under the age of 30, and almost one-third are under 15.

With the Black Decade gradually receding from public consciousness, Algerians may place more strident demands on the government in the future not only on bread-and-butter issues but make louder calls for accountability and transparency. But until that, it is up to the secluded elites to build bridges with young people and cede the terrain.