Photo by Ali Ihsan Cam / Anadolu Agency / Getty Images.

An Ebullient China’s post-2008 global financial crisis belief in its own untapped capabilities seems to be ebbing somewhat in recent months. Its assertive attitude towards its regional neighbors and America’s role in East Asia has slowly morphed since last autumn’s final round of provocative acts into something less strident. By this winter Beijing had moved smoothly into fence-mending and economic courtship mode once more, as it worked to consolidate previous gains made over the past six years, such as the unexpected take up of its new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

The first hint of the change was a restrained response, albeit by Chinese standards, to the U.S. Navy’s freedom of navigation operations in parts of the South China Sea claimed by Beijing. Moreover this came after a spree of island-building in the area over the summer that significantly expanded the Chinese footprint in that disputed area.

Tensions are similarly down with arch-rival Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands dispute in the East China Sea, following the world’s most awkward handshake between China and Japan’s respective leaders, and have remained so. Beijing has also avoided a showdown with America and Taiwan as momentum in the Taiwanese political scene has moved in a more independence-minded direction. There was a muted reaction after the U.S. approved a huge arms package for Taipei as Beijing is waiting to see how the new Taiwanese government acts before it starts revising its current cross-straits policies.

It is important if political events, such as another Taiwan Straits crisis following the election there, do take a negative turn. While all the competing powers in East Asia are jockeying for advantage, the maintenance of peace and stability across the region is the central interest of each individual state actor. For now trade has come to trump territory in East Asia, which leaves space for careful and creative crisis management. However events can still spiral out of control in a vicious circle of action and reaction, which is why Beijing has been moving to turn down the temperature through an active policy of prevention across the region.

The change of direction represents a tactical shift on the part of Beijing rather than a strategic shift in its priorities. Chinese nationalism is still a central tenant of Beijing’s political philosophy as well as a prop for the ruling Chinese Communist Party—the ultimate goal remains a restoration of China to its rightful place as a leading, if not the leading, global power. But while Beijing deals with higher priority issues such as corruption and economic and military reform at home it has recognized that it needs to manage sources of tension along its periphery better. There is a belated recognition that the U.S. has been able to make diplomatic and military inroads in China’s neighborhood following China’s post-2008 shift to a more muscular foreign policy.

Beijing is also looking to bring its substantial recent economic initiatives, collectively known as the “One Belt, One Road” strategy, to fruition. It created the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank to begin to meet East Asia’s infrastructure financing needs and wants persuade other states in China’s immediate neighborhood and beyond to deepen their infrastructure cooperation with Beijing. This is partly to build influence on China’s periphery and abroad, and partly to revitalize China’s struggling economy and boost its impoverished and restless western regions.

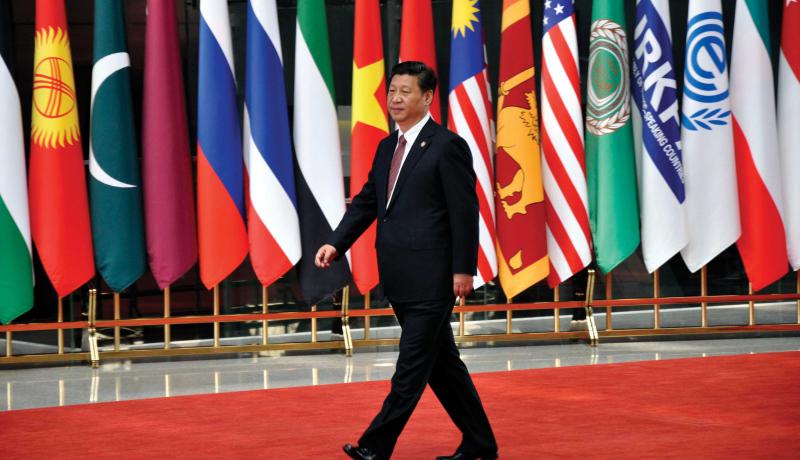

Much of the shift can be traced to the influence of China’s key political personality, President Xi Jinping. Moves by nearby states such as Vietnam and Myanmar towards the U.S. and away from Beijing have not been lost on China’s paramount leader. Xi knows that China is not going to make allies of its skeptical neighbors, but if China’s own house is in order and Beijing is the regional paymaster, he thinks he may be able to make them think harder about choosing sides between the U.S. and Beijing.

Therefore President Xi has chosen to occupy himself more at home, via a draconian crackdown on civil society, a strong anti-corruption campaign and his goal of doubling China’s 2010 GDP as part of his “Chinese Dream” agenda. Abroad he has switched from flexing China’s muscles to prioritizing plans for his New Silk Road. Expect more policy announcements from Beijing brimming with good-neighborliness over the year ahead.

This article was previously published in H Edition magazine.