(U.S. President Barack Obama takes part in a trilateral meeting with South Korean President Park Geun-Hye (L) and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at the Nuclear Security Summit in Washington March 31, 2016)

Trilateral Cooperation enhanced

On March 31, Washington hosted the 2016 Nuclear Security Summit (NSS), gathering more than 50 leaders from all over the world. Despite the clear absence of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and Iran, the Obama Administration’s commitment to fostering nuclear non-proliferation in the Asia-Pacific region remains on the top of Washington’s agenda. As stressed by President Obama, Trilateral Cooperation represents the most important tool for building and fostering stability in Asia-Pacific, especially considering the DPRK’s nuclear ambitions along with the expansion of the PRC’s territorial claims in the South China Sea, both of which endanger the fragile regional security architecture.

The recent talks joined by both President Park and Prime Minister Abe aim to design a new and shared strategy to contain and counterbalance Pyongyang’s increasing level of assertiveness, which is considered an unpredictable threat to peace and security. Despite recent frictions in Japan-South Korea relations, especially those involving relevant issues such as “comfort women” and territorial disputes over the Dokdo-Takeshima Islands, the fourth DPRK nuclear test has represented a far more urgent issue that needs to be addressed by both nations.

Since President Obama has unveiled the Asia-Pacific rebalance strategy during his memorable address to Australian Parliament in 2011, Japan’s and South Korea’s roles have become fundamental for the recalibration of the political and strategic American presence in the Asia-Pacific region. The American military presence in the region highlights Washington’s commitment to the protection of both its economic and security interests, which are expected to expand in the foreseeable future.

Increasing the level of engagement with traditional alliances, while welcoming economic integration of the Asian Nations under the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP), is crucial for shaping a new and more ambitious agenda for cooperation in the region. A series of strategic initiatives will expand and foster a projection of U.S. armed forces power, deterring aggression and promoting security relationships on the model of those already established with Australia, Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan and Singapore. Enhancing the level of military cooperation with Japan and South Korea is a cornerstone of Washington’s rebalance efforts in Asia, especially in the aftermath of the DPRK’s nuclear threats. Washington’s strategic architecture and crisis response mechanisms are expected to be further defined in the next Defence Trilateral Talks (DTT).

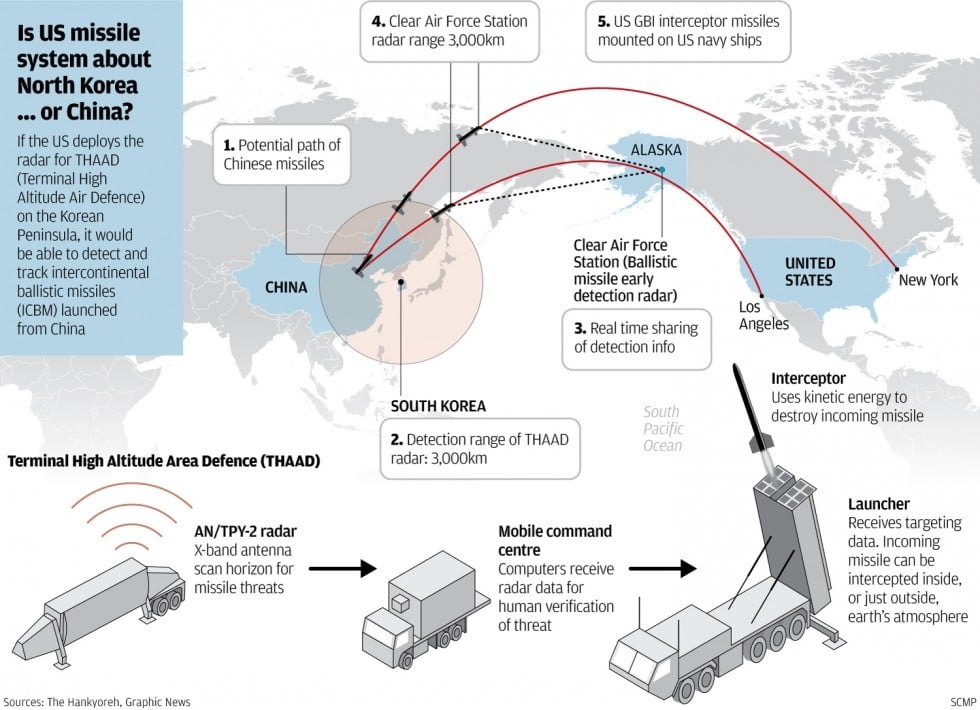

The recent crisis precipitated by North Korea has raised the threat perception of both Japan and South Korea, fostering the promotion of a new level of strategic preparedness and cooperation with Washington, a major defence partner of both countries. In less than a month, South Korea inaugurated a pragmatic strategy to respond to Pyongyang’s provocations: the deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) System, which is close to being finalized, as was recently stressed by Defence Secretary Ash Carter. In March, Seoul launched joint military exercises, the largest ever seen, in cooperation with nearly 17,000 U.S. troops, proving the harsh reactions of Pyongyang. While the Obama Administration has stressed that there is no plan to launch an invasion of the DPRK, the joint exercises aim to develop further synergies while also sending an important signal to allies and challengers of the American security architecture in the region.

In regards to Japan, on March 29 Tokyo’s defence posture marked a major shift after the recent enactment of security legislation strongly supported by Prime Minister Abe. It expands the scope of Japan’s strategic contributions to overseas missions, while also allowing for Japan’s Self-Defence Forces (SDF) to engage in collective self-defence and fighting alongside allies. Prime Minister Abe is actively pushing the idea of Japan’s pivotal role in proactively contributing more than ever to the peace and stability of both the region and of the international community.

The Japanese SDF’s new right of collective self-defense could, in the event of a crisis, provide an important contribution to the protection and assistance of the U.S. forces deployed in the Korean peninsula. Besides the evident threat represented by the advancement of Pyongyang’s pursuit of nuclear power, the increasingly provocative behavior of the DPRK poses a question over the ability of Washington to effectively maintain a prominent role in preventing further nuclear proliferation. However, the threat of nuclear retaliation against the DPRK is still an effective means of deterrence against any foolish attack coming from Pyongyang. The resumation of the DPRK’s nuclear testing has inflamed the region; it is just the prelude of upcoming tensions, originated by Kim’s unfulfilled desire to consolidate his trembling power through military might.

Beijing’s long shadow in the Korean Peninsula

On the sidelines of the NSS, President Obama held a meeting in Washington with President Xi Jinping to tackle a few important issues in Washington’s security agenda for the Asia-Pacific region. Specifically, discussions revolved around American plans to deploy an advanced land-based missile defence system, known as THAAD in South Korea, and around the rising military presence in the South China Sea, an area of key importance for the United States. The South China Sea remains the main source of tension between Washington and Beijing. Establishing a shared mechanism to manage the South China Sea is a critical tool in reducing the possible causes of conflict or unintended accidents that could escalate into a serious crisis.

Recently, Beijing has expressed its commitment to support the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula in order to foster regional stability and prevent further incidents originated by the provocative behaviour of the DPRK. On the other hand, China also firmly opposes the deployment of the THAAD, which is considered a threat by Beijing due to its strategic coverage (beyond the Korean peninsula and into China) that has the power to intercept missiles fired from China’s inland bases.

(Terminal High Altitude Area Defence explained, Source South China Morning Post 2015)

Beijing’s decision to bolster additional sanctions against the DPRK comes after the U.N. Security Council imposed new sanctions on the Hermit Kingdom’s nuclear program, depriving it of important economic revenues and resources. It has been considered a major shift in PRC-DPRK relations, which have already been tense due to the recalcitrant Kim’s rejection of any attempts at mediation proposed by the Chinese. In the past, China has interceded for the repeated transgressions of the DPRK caused by nuclear ambitions or aggressive behavior, but the recent nuclear tests conducted, despite Beijing’s warnings, have given rise to a large political and security impasse for the CCP. China has, for a long time, maintained a special relationship with the DPRK, considering it a valuable client state and an important buffering zone against Washington’s military presence in South Korea. China’s decision to increase the pressures on the DPRK, after insistent demands of Washington, unveils China’s double approach in dealing with such a dreadful neighbour.

While Beijing is often reluctant to intervene in other country’s foreign affairs through the imposition of sanctions, especially jointly with Washington, the DPRK’s irresponsible behavior is jeopardizing China’s traditional authority and influence in the Korean Peninsula. Thus, China is not willing to tolerate any further transgressions from Pyongyang that could ultimately undermine its authority in the region. Yet, this crisis has offered a valuable opportunity for Beijing to promote itself as a responsible power in the international community. By playing a pivotal role in resolving the nuclear crisis, China could reassure Washington and other Asian powers about its determination to pursue a peaceful neighborhood policy and thus reduce the level of mistrust due to China’s hegemonic ambitions.

Most importantly, compelling Pyongyang to abide by the rules and regulations of the Non-Proliferation Treaty will not only prevent the escalation of a dangerous confrontation in Beijing’s backyard, whose consequences would certainly represent a major crisis for CCP’s leadership, but it would also reduce Washington’s desire to establish advanced missiles defence systems. Despite China’s determination to seize the momentum, a dangerous escalation of the DPRK’s crisis could be beyond Beijing’s ability to solve it, undermining the CCP’s credibility and authority. Yet, the outcome represented by the emerging confrontation of the two major powers remains the central dilemma; the alteration of the power balance in the region would certainly reshape the fragile strategic balance maintained so far.

The emergence of a new crisis in the Korean Peninsula remains a tremendous threat to the core regional stability. From a strategic perspective, this event has played an important role in fostering the level of engagement of Japan and South Korea under the auspices of Washington. The Obama Administration is committed to preserving balance in the region; it is pursuing a more dynamic engagement with China, who is acting as a proactive supporter of regional security rather than a representing an additional source of instability and fragmentation. Yet, the future of the region remains highly dependent on Beijing’s desire to embrace a new and more assertive directive in reaffirming its leadership in Pyongyang, a critical step in promoting the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula. Promoting stability without risking substantial changes in the fragile status quo could eventually produce the most favourable outcome for Beijing.