In 1947, what was then the British colony of India, alongside getting freedom from the British Raj, partitioned into what we know today as India and Pakistan (note: Pakistan in 1947 comprised of East and West. In 1971, the East partitioned into what is now Bangladesh). Pakistan was claimed as a land for the Muslims. However, one third of the total Muslim population in the British colony were to remain in present-day India.

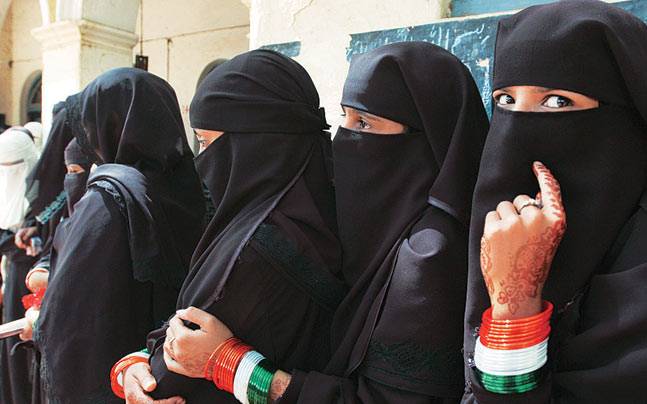

Muslims are a minority in India today. They have been persecuted, as any minority groups are everywhere in the world, and as their Hindu brothers across the border, do not always feel at home in their own country. The Indian Constitution has mandated the protection of minorities, the promise of fundamental rights—equality before the law and against discrimination based on religion. But over the years, these Indian Muslims have had trouble finding their voice and a sense of community.

Ten years before partition, the ruling government realized that Muslim personal laws governing marriage, divorce, inheritance, and gifts were different from the country’s general citizenry. The realization led to the decision that different rules warranted recognition. In 1937, the Muslim Personal Law (Sharia) Application Act was passed. Muslims wanted to be governed by the laws that their religion mandated, and the 1937 Act allowed them just that. Following the 1937 Act, the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act of 1939 allowed women the right of divorce in accordance with Islamic principles. In 1986, the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act was passed in response to the famed Shahbano case.

Shahbano was a 65 year old mother of 5, who, upon being divorced, had filed a suit for maintenance. The case went all the way up to the Supreme Court, where she was awarded a fair sum. This was decision was later overturned by the passing of the 1986 Act (parliament was pressured by Islamic orthodoxy) to qualify women’s right to maintenance.

In 2014, in the case of Shamima Farooqui, the Supreme Court of India reinstated the Shahbano case and nullified the 1986 Act, allowing women the absolute right to maintenance. The question presented to the court was whether a Muslim woman in India was entitled to maintenance under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure like all other non-Muslim Indian women—or were they relegated to the chauvinistic implications of the 1986 Act.

In what begins as a flowery novel, Justice Dipak Misra writing for the court, condemned the lateness of decisions of the family court (this decision, in particular, took 14 years) as abysmal and went against the foundations of the creation of a family court. He went on to award Shamima the highest possible maintenance, under the Code of Criminal Procedure, not the 1986 Act.

Today we have a brave Shayara Banu going to the Supreme Court—asking them to recognize her as a citizen of India and be awarded equal protections under the Constitution – challenging the “triple talaq” or “triple divorce” rule under the “Sharia” in India. She is not challenging it on the basis of any religious grounds—but as a citizen of a country that affords her the right to be treated the same as any non-Muslim would.

The triple divorce is another adulteration of religious mandate in the Muslim world. Following this, a husband may simply declare that he is divorcing his wife—three times in one sitting—and the divorce is final. The threat of such an instantaneous divorce is so grave that women, such as Shayara Banu, stay in abusive relationships for years so as not to be cast aside. Divorce is extremely taboo in India and a women is only as good as her husband’s home.

The question is, where does this tradition stem from? Like many interpretations of the sharia throughout the world, this too finds its roots in the Qur’an—manipulated to suit the patriarchal society it is catering. The verse in question here states:

“O PROPHET! When you [intend to] divorce women, divorce them with a view to the waiting period appointed for them, and reckon the period [carefully], and be conscious of God, your Sustainer.” (65:1) The mention of the number three comes from this verse: “Now as for such of your women as are beyond, the age of monthly courses, as well as for such as do not have any courses, their waiting-period – if you have any doubt [about it] – shall be three [calendar] months; and as for those who are with child, the end of their waiting-term shall come when they deliver their burden.” (65:4)

The “waiting period” here refers the female menstrual cycle. The husband is asked to wait a menstrual cycle—a month—before he pronounces the second divorce, and so on. And to do away with any ambiguity—it says to wait three months. This cycle of three has been interpreted to mean you can pronounce a divorce three times, in one sitting, and thereby unilaterally without consequence, finalize a divorce.

The chapter goes to explain how a woman is to be kept with honor and “in the same manner as you live yourselves” during the waiting period, and in the event the husband does not wish to go through the divorce (i.e. before the third month and therefore, the third pronouncement) he must “either retain them in a fair manner or part with them in a fair manner.” This must happen in the presence of two witnesses—known among the community for their truthfulness. The purpose of this three month waiting period is similar to that of a separation requirement in Western jurisprudence.

This is the process that has translated into a “triple talaq” in India, which Shayara Banu is protesting. This is the wrong she wants put right. She has done this in a manner where the Supreme Court is forced to hear her, not as a Muslim and therefore subject to patriarchal interpretation of an equal religion, but as an equal citizen under the secular Constitution. The result of this case will shape the lives of women, not just Muslim women, throughout India for years to come. Indian women will owe their equality to Shahbano, Shamima and Shayara.

Timeline