Source: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world-2015/maps

Accepting the Republican nomination for President, Donald Trump called NATO “obsolete.” He has since repeated his tenet that America’s allies should pay us for the security we provide them, and raised doubt around expectations that we would respond to attacks on NATO members.

Trump is not the only person to complain about alliances. Others, for various reasons, dislike our relationship with Saudi Arabia or our arrangements with Pakistan. During the 1980s, many spoke of Japan as an enemy, despite our alliance.

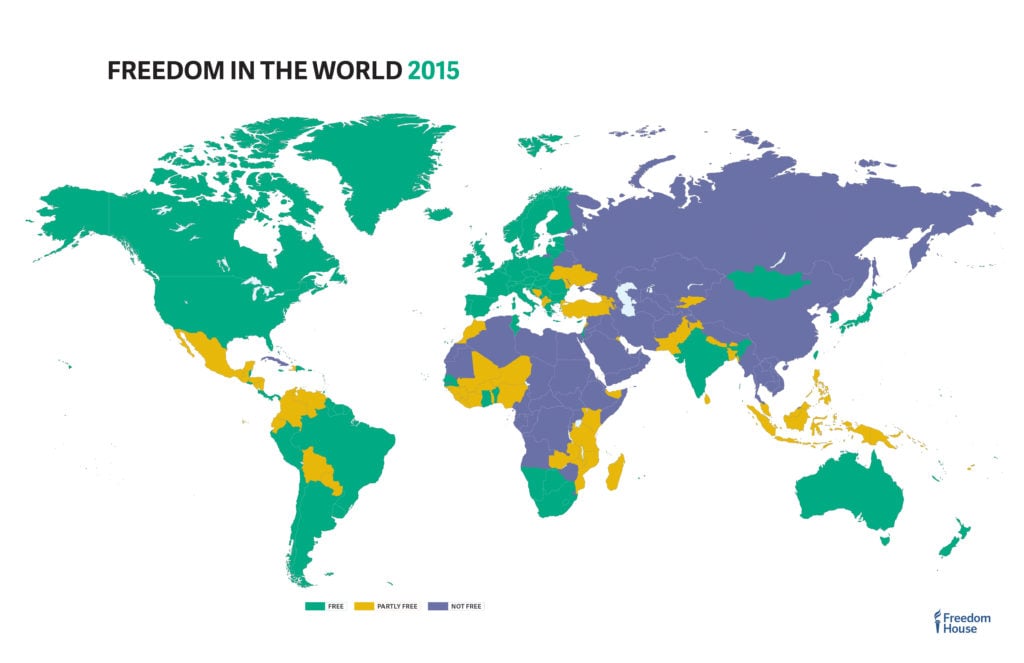

Alliances—and exclusions from them—imply priorities. U.S. foreign policy must protect our vital needs, but we often forget that those revolve around the principles on which America created itself. A hypothetical update of our current alliance structure illustrates how we might enhance our tangible security – and affirm our deepest values.

NATO, ANZUS, and the U.S.-Japan treaty encompass a preponderance of societies in which civic liberty, democracy, and personal leeway to live by one’s own choices prevail as a norm. Currently these alliances’ history and configurations raise impressions that they are primarily aimed against Russia or China. A whiff of power politics obscures the role of freedom in our relations—or belies our profession of that priority, in some eyes.

To make our motives plain, the U.S. could initiate a combination of those alliances into a single security community, of collective defense. This reconfiguration would turn our focus toward what’s being protected, away from any country. With this community as our primary alliance, we would define our security concerns by our core value.

There are anomalies, which an initiative must address up front. Some NATO members, notably Turkey, are regressing in the practice of impartial rule of law. The community would need a membership review process. A number of free societies are not members of the named alliances, including Sweden, Switzerland, South Korea, Taiwan, Israel, and some Caribbean islands.

Some of these nations should be invited into the new community immediately. Some may raise too much controversy and should be protected under other arrangements. Solutions must be part and parcel of this concept; truly free societies should be defended, and oppressive regimes cannot be members.

A diplomatic corollary should follow. The new security community must aim not only to protect societies where rights and democracy prevail, but encourage those practices. The community would aspire to have all nations as members: any society that converges with members in habituation to rights and democracy would be approached for collaboration, and ultimately membership. Relations with non-members would grow closer or more distant according to this compatibility. Diplomacy would promote rights and democracy where today’s promotion programs are not welcome.

It would also permit us to address interests that sometimes play against our values. Relations with China, for example, would balance our shared economic interests, and that state’s commitment to public welfare, against their non-democracy, human rights abuses, and expansionism. Instead of the oxymoronic “frenemy,” we would call them something like “a 3.5 out of 10,” and tell China how we could grow closer. Active management of relations would give teeth to diplomacy; those who move away from liberal norms and amicable behavior put the benefits of collaboration at risk. Economic sanctions would not be the only measure short of war to counter an adversary. Relationship upgrades offer carrots with no pandering.

The community would limit its purview to matters of security. Defending freedom implies defending its tangible underpinnings, but economic interests not essential to sustain freedom would lie outside the community’s focus. However, in our belief that prosperity’s growth promotes freedom, U.S. policy should, concurrently with this initiative, launch a long term campaign for a new WTO round, and eschew new regional trade initiatives.

The TPP and TTIP agreements should be pursued to completion as a matter of credibility. But, while they liberalize trade to some extent, such deals usually gain domestic approval as geopolitical supports. In the case of TPP our leaders have said they want the U.S. rather than China making the rules, while in TTIP’s case binding western allies together implies containment of Russia. Trade liberalization should be promoted impartially, as a stimulant to freedom, to express our principles. The WTO requires consensus of all 180-odd members, and an initiative for a new round would exhibit our desire for global growth, and development for all.

In pure terms of security, the community’s projected membership carries a preponderance of capacities. Relatively few threats arise on land borders, and U.S. and European nuclear capabilities will deter outright attack for decades to come. Most concerns are in guerilla warfare, in maritime settings, in terrorist attacks, and in cyberspace. The likely members have technical and organizational capacity for strong defense and deterrence. At the very least, hostile efforts will become more and more expensive. If the community follows the proposed inclusive diplomacy, the costs will become less and less worthwhile, and hostility toward this community would indicate hostility to freedom itself. For moral and material reasons, war against free societies could almost be taken off the table of international relations.

As campaign rhetoric turns to topics such as NATO, politicized claims “for our allies” or “against NATO” might well eclipse the values that those edifices protect. Americans should focus on the values and accept flexibility on the edifices, during the campaign and throughout the volatile times we live in.