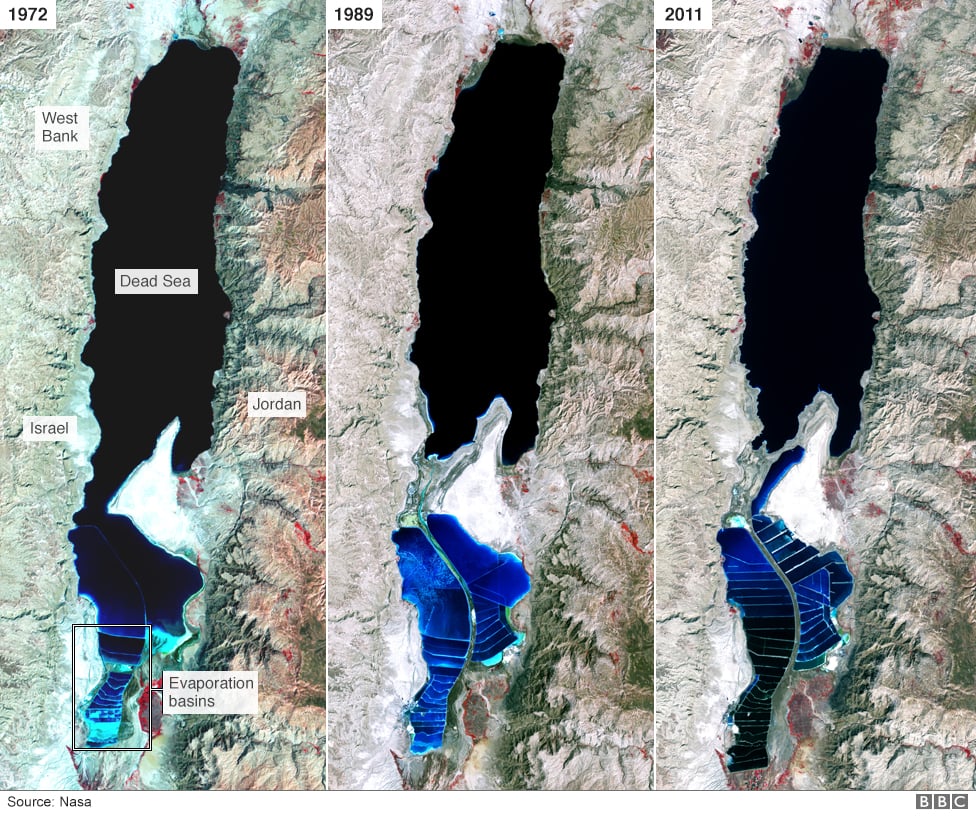

Changes in the Dead Sea over time (NASA and BBC).

One of the most important lessons in economic theory is that we live in a world of scarcity. At a time when we are witnessing some of the largest refugee flows since World War II, highlighting the linkages between water resources and global affairs is crucial.

The current debate looks at linkages between water scarcity, refugee flows, and conflict. When there is only a finite size of a lake like the Dead Sea (the lowest spot on earth and one of the saltiest water bodies) whose level has dipped precariously in recent decades, several tricky aspects of ‘tragedy of the commons’ arise. The Dead Sea’s water level continues to drop at an alarming pace of 0.8 to 1.2 meters per year and its surface area is shrinking accordingly. If no action is taken to remedy the situation, the further decline is likely to cause more severe environmental, cultural, and economic damage, and it is estimated that, if left unattended, the Dead Sea will reach a new equilibrium at an elevation that is about 100m below the current level.

Numbers are also the nemesis adding to the lake’s environmental degradation: refugees from Syria have increased Jordan’s population by one-tenth, putting major pressure on budgets, public infrastructure, and labor markets. The massive and rapid influx of refugees has also strained already weak infrastructure, as more than 80 per cent of refugees live within local communities rather than in the refugee camps, and since the arrival of Syrian refugees, water consumption per capita dropped in Jordan from 88 to 66 liters.

On the other hand, evidence suggests that water can become an economic win-win agent and a ‘lubricant of peace,’ especially when basins transcend jurisdictional boundaries. Jordan and Israel are finally beginning to evolve solutions by implementing the Red Sea-Dead Sea Water Conveyance Project (the Red-Dead project) which will play a crucial role in saving the Dead Sea and meeting Jordan’s rising needs on water.

In its following phases, the Red-Dead project entails transferring up to 2 billion cubic meters of seawater from the Red Sea to the Dead Sea.

When Israel and Jordan signed a peace agreement, the idea of laying a pipeline from the Red Sea to the Dead Sea began to gain momentum. Thereafter, in 2005, Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority jointly asked the World Bank to lend its resources to the project’s feasibility study. They also requested an investigation into any potential environmental impact. The study found that it was viable and the three partners signed an agreement in December 2013.

The first phase of the Red-Dead project (with an estimated cost of US$900 million) will be 180 kilometers long and will pass through the Jordanian territory. Construction is planned for 2017 and will be completed in 4-5 years. About 300 million cubic meters (mcm) of water will be pumped each year under which a desalination plant will be built in north of Aqaba, Jordan’s only seaport, producing some 65mcm of fresh water per year. The remaining 235mcm (of mixed brine and seawater) will be pumped into the shrinking Dead Sea.

Another cooperation-inducing aspect is ‘water swapping and sharing’: Jordan is interested in selling desalinated water to Israel while buying water from the Sea of Galilee. Simply put, Israel wants water in the south, and Jordan needs water in the north where the majority of refugees are living. Hence, in principle, a Jordanian-Israeli water exchange (from the Sea of Galilee to Amman, and from Aqaba to Eilat) would make economic, environmental, and political sense.

Water exchange between Israel and Jordan (ynetnews.com).

In spite of some differences, the three beneficiary partners (Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority) have succeeded in isolating this ambitious, strategic project from the calculus of conflicts in the Middle East. Negative criticism of any sort largely emanates from environmentalists whose concerns have chiefly been related to the effects and impact from discharge of seawater and brine from desalination into the Dead Sea.

Ultimately, the greater need for water may outweigh potential environmental or political concern. Aside from saving the Dead Sea, the Red-Dead project could offer huge benefits to Jordan and neighboring countries: because the Dead Sea is more than 400m below sea level, channeling water down to it could provide the opportunity to generate electricity or desalinated seawater, or both. Moreover, the scope of the Red-Dead conveyance could be expanded, depending on project financing, with greater benefits accruing with larger scale.

The Dead Sea is a site of cardinal international cultural, environmental, and touristic importance. The development of such a strategic project cannot see realism without international support. While the refugee crisis necessitates a response, it is also an opportunity to re-examine and re-assert the benefits of the Red-Dead project.

We all know how severe the state of water resources in the Middle East is. And we know that the main rivers and lakes are shrinking at a fast pace. Yet, the nexus between water and peace is much less explored. The Red-Dead project is expected to make such a contribution. Thus, the whole world should start backing the completion of the Dead-Sea project without distraction.