Sunset in Siberia, 2018. J.Quirk

Reports from Russian announced that Vladimir Putin won over 76% of the votes in his reelection bid March 18, with turnout over 67%.

The view from Siberia was a little different.

OSCE, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, sent nearly 600 short-term, long-term, and other election observers to Russia. In its next-day report, OSCE noted that in an environment of state-owned television networks, “television coverage was characterized by extensive and unchallenged reporting of the incumbent’s official activities.” More curiously, OSCE described election day itself as technically competent but ultimately spoiled. “Overall,” it judged, “election day was conducted in an orderly manner despite shortcomings related to vote secrecy and transparency of counting.” The election was run well, it seemed to judge, except for the voting and the counting.

OSCE dispatched more than 200 pairs of short-term observers, each with a local driver and interpreter, all over the country. Some observers had done this many times across the Balkans and post-Soviet space, while for others it was their first mission. Observers included chief elections administrators from cities across the U.S., EU “Former Ministers of Something,” and at least one former member of the U.S. Congress.

A voter in Siberia, March 18, 2018. J.Quirk

My partner and I joined four other teams on an overnight flight to a mid-sized Siberian city; from there we drove four hours to smaller communities. The flat, snowy landscape was broken up only by lines of birch trees and the occasional petrol station. We benefited from the beginning of spring weather and reliable roads. Other teams enjoyed 15⁰C resort-living in the south or the chance for a bit of tourism in St. Petersburg, while some endured flying ten or more hours east, or driving off the road in a snowstorm.

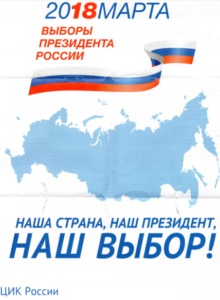

After two days of briefings in Moscow, the short-term observers’ work begins the day before the election. Our responsible driver and informative polyglot kept us safe and on course. We located and inspected the polling stations in a hospital, at a football stadium, at a coal mining company HQ, and in several schools. People were generally finishing or finished with preparations for the next day. Across the towns, there were a few posters and billboards for candidates. Most, though, were targeting turnout with patriotic white, blue, and red calls to vote for “Our country, our president, our choice.”

Voting was brisk in the morning, but we had a question about mobile voting. Large percentages of voters in some polling stations were scheduled to be individually visited, handed a ballot, and have their vote collected in a mobile ballot box. These visits are a nice service for homebound voters, but they are not followed by international or local observers. In cases where mobile voting was intended to serve 20 or 30 percent of the polling station’s list of voters, we were told it was because there were many older voters. But the challenge to visit 200 or 300 voters in a few hours seemed substantial.

“Our country, our president, our choice.” J.Quirk

The counting itself gave us as much pause. It was at the individual polling stations, not regional or central locations, where the actual counting was done. In theory, a ballot box would be emptied on a large table. One by one, each and every ballot would be displayed to the polling station workers and to any observers. (There were observers from several candidates or parties at most polling stations.) “A vote for Candidate X,” and anyone could question it. It would make for a long but accurate count. Instead, the big pile of ballots was divided by four or five poll workers into new piles, one for each candidate. Observers watched from a distance and could see some accuracy but not each ballot. Each poll worker counted her pile (poll workers were overwhelmingly women in our area), and in turn announced simply, “Zhirinovsky, 22”, “Sobchak, 44,” “Putin, 701,” etc. There was no recounting of someone else’s pile, and no obvious reconciliation among the number of the day’s voters and the total of the candidates’ piles. (The next-day OSCE report noted that many observation teams reported this same practice.) These tallies were recorded, entered into a computer, and sent. The ballots themselves were sealed in bags and delivered to the regional center, where we were told they would be locked in a room for a year. There seemed to be no built-in sampling of the bags of ballots, for example – “this one says Yavlinsky, 18 votes, let’s check it for accuracy.”

This doesn’t mean there was fraud at this stage: I watched one woman count her Grudinin pile. I was several feet away, but she seemed to be counting earnestly, flicking the top right corner of each ballot in her pile with her right index finger. She and I got the same number, but she went through the whole pile only one time.

At least one more difference between this election observation mission and others on which I served was the motivation of the host country. In Albania’s 2011 local elections, for example, they needed to demonstrate that they had the technical capacity and political commitment to hold free and fair elections, as one small step on the long road to the EU. Instead, the race for Tirana mayor was extremely close, the national election commission overruled the local ones in some key ways, and Edi Rama launched a series of controversial appeals before officially losing by just 81 votes.

Russia and President Putin didn’t seem to have to appease international observers, only national public opinion. Live Internet webcams inside polling stations across the country captured a number of apparent irregularities, including ballot-box stuffing, that were shown on foreign newscasts around the world. But it seemed to some of us that an inspiring turnout to match the candidate-choice results was a higher priority than impressing temporary guests.

A final note: in some ways, these are not just technical, legal administrative matters, but foreign exchange programs. We met dozens of people working the polls, but also on airplanes, in hotels, in shops and cafes, and elsewhere. Most Russians were met were friendly, cooperative, and interested in doing their work while we did ours. The political atmosphere prevented more opportunities for rich, personal exchanges, but I hope my partner and I were as effective unofficial ambassadors for our countries as so many of the Russians we met were for theirs.