“America’s Diplomats”, a new television special produced by the Foreign Policy Association, seeks to explain the world of professional diplomats to average citizens, people who, through no fault of their own, have little occasion to interact with Foreign Service Officers or to discuss the inner workings of the Department of State.

As is fitting of the Foreign Policy Association—and in keeping with reality—it offers a positive and hopeful message. A number of themes are woven in and out of the narrative. Among these are the tasks that diplomats actually undertake, popular American attitudes toward diplomacy, the evolution and professionalization of the field in the United States, and the need to balance our diplomats’ need for personal security with their need to accomplish their mission. Allow me to touch upon a few of these themes without repeating the details of the program.

Americans have long had a disdainful attitude toward diplomacy and diplomats, seeing the whole endeavor as something elitist, foreign, expensive, and possibly deceitful.

Ambrose Bierce, the author of The Devil’s Dictionary (1906), defined diplomacy at “the patriotic art of lying for one’s country” and a consul as “a person who having failed to secure an office from the people is given one by the Administration on the condition that he leave the country.”

Yet diplomacy was essential to the birth of the United States. Washington’s forces would never have prevailed without the alliance with France. France not only provided finances, troops, and a fleet, but it also distracted Britain’s attention by threatening its holdings in far-flung corners of the world. (Remember, the British army abandoned the occupation of Philadelphia because they suddenly needed the troops to defend the West Indies.)

From the beginning, the young American republic cut corners when it came to diplomacy. Unwilling to pay the salary of “ambassadors,” the United States sent “ministers,” diplomats of a lower rank, to represent it in foreign capitals.

This not only reduced the status and influence of American diplomats, it also created a dilemma for other countries. Based on the rules of reciprocity, European powers would not send ambassadors to a country that sent them ministers, but they were hard-pressed to find qualified diplomats who would willingly cross the ocean and live in “the American wilderness” for a minister’s salary.

Relative isolation made it easy for the United States to neglect diplomacy for a while. After all, the U.S. was hidden behind large oceans. The oceans were controlled by the British fleet, and the British—after the War of 1812, at least—found that they already had enough enemies and that life would be easier if they could just keep the Americans on their side.

Most U.S. contact with the outside world consisted of trade. American businessmen resident in foreign ports were asked by the government to act as consuls, looking after U.S. interests, in their spare time. Still, the Consular Service, being business-oriented, was held in somewhat higher esteem by the public than the Diplomatic Service.

The two services interacted little with each other, and both suffered from low salaries, nonexistent benefits, and the consequences of a spoils system of appointments, a system that Teddy Roosevelt denounced as “wholly and unmixedly evil,” “emphatically un-American and undemocratic,” and something that no “intelligent man or ordinary decency” could endorse.

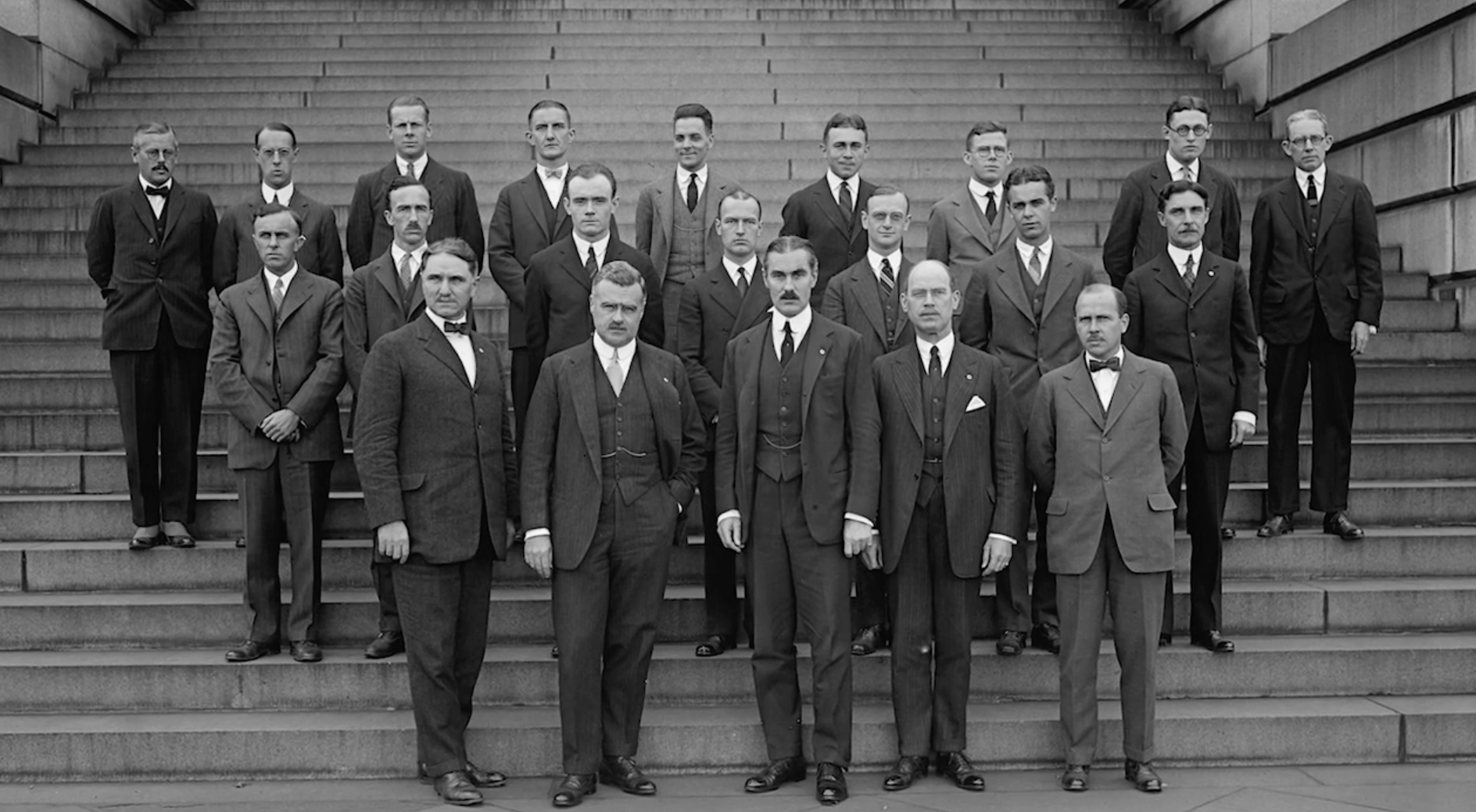

As the U.S. grew—and its contacts with the outside world multiplied in number and evolved in kind—a greater sense of professionalism had to be forced upon its diplomacy. The Consular Service forged a merit-based system in the early 1900s.

Leaders of the Diplomatic Service, on the other hand, preferred to rely on men of independent means and saw low salaries as a way to weed out undesirables. With the onset of World War I, the pressures to modernize came in accelerated form.

A key turning point finally came with the Foreign Service Act of 1924, also known as the Rogers Act. The Rogers Act merged the Diplomatic Service and the Consular Service into the new Foreign Service of the United States; established a meritocratic personnel system, including standardized entrance exams; and created or extended allowances and benefits. The Foreign Service School was also established in 1924, which was replaced by the Foreign Service Institute in 1947.

Still, even today, the system is not fully professionalized. “America’s Diplomats” suggests that perhaps 30% of ambassadors are political appointees (albeit supported by professional diplomats). Some of these, even if not professional Foreign Service Officers, are highly qualified. Others, such as some campaign donors, are potential embarrassments.

The question of diplomats’ personal security is a key theme in “America’s Diplomats,” both early in the show and toward the end. The focus is clearly influenced by the Benghazi controversy.

Yet it is not presented as a straight-forward question of protecting personnel, as it is often depicted in Washington. Rather it is a trade-off. The Foreign Service does not want to leave its people exposed to dangers unnecessarily, but it also views excessive security measures as obstacles that get in the way of doing its mission.

It resists measures that separate its diplomats from the government and society that they are supposed to be reporting on. Finding the balance is an endless task, and one that does not always end happily.

Although, as many politicians have said in the past few years, no U.S. ambassador had been killed in the line of duty in over 20 years, they picked that number consciously. American ambassadors have been killed in the line of duty in 1988, 1979, 1976, 1974, 1973, and 1968.

Other, lower-ranking diplomats have been killed since then. (The American Foreign Service Association lists 247 State Department personnel who have died in the line of duty since 1780, although most of the earlier cases were lost at sea or died in epidemics.)

None of this is to dismiss the tragedy of Benghazi but rather to question the politicization of the event when the previous cases were not politicized, and the consequences for the future of diplomacy.

“America’s Diplomats” is an interesting and informative introduction to the things that diplomats do. It strives to use information to overcome the lingering disdain that people may carry toward diplomats and diplomacy. I suspect the producers would also like to see the process of professionalization completed and the politicization of foreign policy overcome, but those are even taller orders.

To get more information, please visit the America’s Diplomats website.