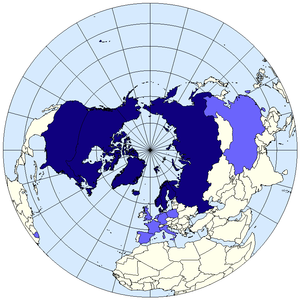

Arctic Council Map. Permanent members in dark blue; observers in light blue.

The second major event of the week in Tromsø was the biennial Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting. Representatives from all of the permanent member states of Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States were in attendance, along with representatives from observer states. Climate change was of course high on the agenda this year, but seal hunting and shipping were also main issues of debate.

The Arctic Council was established by the Ottawa Declaration in 1996, and its main goal is to promote high-level multilateral dialogue on the environment, sustainable development, and climate change in the Arctic.

Accomplishments

The Arctic Council (AC) issued the Tromsø Declaration as a summary of the work of the two-day conference.

- Climate Change in the Arctic: The AC noted the increasing rate of melting in the Arctic and thus underscored the commitment of all AC members to reaching an international agreement in Copenhagen in December. They also discussed more immediate measures that could be taken, such as combatting methane emissions by working with the Methane to Markets Partnership.

- International Polar Year and its Legacy: The AC encouraged further international scientific cooperation even though the IPY has concluded. Projects like the Sustaining Arctic Observing Networks will continue work in this vein.

- Arctic Marine Environment: This section mostly focuses on shipping. As such, the AC approved the Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment, a document which discusses possible future scenarios in the Arctic based on two variables: governance stability and demand for resource and trade. The AC is also committed to carrying out more work on the creation of an international search and rescue operation force.

- Human Health and Human Development: The AC pointed out the risks from the environment facing Arctic residents, such as transnational pollution and its harmful effect on breastfeeding babies. The document also highlighted the importance of education in the region. The AC briefly mentioned the University of the Arctic, an interesting educational network between universities located in the High North. Students enrolled in these universities often focus their studies on sustainable development and participate in the north2north exchange program between the various Arctic universities.

- Energy: While recognizing that oil and energy can “contribute to sustainable development in the region,” more work needs to be done in reducing environmental risk. The AC also welcomed increased research into renewable energy in the Arctic.

- Contaminants: The AC touched upon the need for more international controls over certain contaminants in the Arctic that are currently unregulated. The AC also welcomed the creation of a new steering group to address the specific concerns of indigenous people in relation to contaminants.

- Biodiversity: The AC underscored the importance of programs such as the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment and the Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Programme and encouraged further research on species in the Arctic like polar bears. The AC also made note of the unique contributions the Inuit can make in regards to conservation and species management.

- Administration and Organization of the Arctic Council: A new series of meetings at the deputy ministerial will take place, giving the Arctic Council greater political clout.

At the end of the meeting, Norway passed the chairmanship to Denmark, who will head the Arctic Council through 2009 and host the next ministerial meeting in 2011.

Russia

Russian FM Lavrov next to the President of the Norwegian Saami Parliament. © Jesper Hansen

Following the conference, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov denied that Russia is building up its forces in the Arctic. He remarked, “We [Russia] are not planning to increase our military presence in the Arctic and to deploy armed forces there,” – a statement that is somewhat at odds with the Russian National Security Council’s plan for Arctic development through 2020. That document outlined Russia’s plans to beef up its military capabilities in the Arctic, but Lavrov said that these were just measures that “provide for strengthening the potential of the coast guard.” Russia seems to be papering over its aggressive development strategy with diplomatic niceties.

Inuit

The Inuit were not so happy with the convening of the Arctic Council. On Tuesday, a day before the meeting began, the Inuit Circumpolar Council released a declaration on Arctic sovereignty. In the document, ICC Chair Patricia Cochran is quoted as saying,

“Our declaration addresses some of these questions from the position of a people who know the Arctic intimately. We have lived here for thousands and thousands of years and by making this declaration, we are saying to those who want to use Inuit Nunaat for their own purposes, you must talk to us and respect our rights.”

However, the declaration noted that it is

“not an Inuit Nunaat declaration of independence, but rather a statement of who we are, what we stand for, and on what terms we are prepared to work together with others.”

The Inuit have long felt excluded from debates on the future of the Arctic. In recent years, they have been included more often in summits and debates such as at last year’s Arctic Council Meeting in Greenland, yet mostly as a token presence. All the same, governments like Canada’s rely on their presence in the northernmost reaches of the country as a foundation for their sovereignty arguments. In the 1950s, many Inuits were forced from their ancestral homes to found new settlements in the High North in order to bolster Canada’s claims over the area.

Non-Arctic States

The Arctic Council denied permanent observer membership to the EU, China, Italy, and South Korea, due to a dispute between Canada and the EU on seal hunting. Brussels is expected to place a ban on seal products, a move that has angered Canada, which claims the seal hunt is sustainable and not cruel. Canada believes that a ban would inevitably lower demand for seal pelts and harm the Inuit economy, even though the EU would put an exception on indigenous hunting. Denmark is also opposed to EU plans, since seal hunting forms a large part of the Inuit economy in Greenland. And while Norway engages in seal hunting, ththe country ey actually favored EU accession due to the close ties between the two over the issue of oil and gas resources. The EU is looking to Norway to supply more of its energy needs as Russia becomes a less reliable provider.

Favoring multilateralism, Norwegian Foreign Minister Jonas Gahr Støre observed, “Norway shares that view [on the seal ban] with Canada. But for Norway, that’s yet another reason to invite the observers in.”

Canadian Foreign Minister Lawrence Cannon skirted the issue of the seal hunt when commenting on the Arctic Coucil’s rejection of the EU membership bid. He said,

“Canada doesn’t feel that the European Union, at this stage, has the required sensitivity to be able to acknowledge the Arctic Council, as well as its membership, and so therefore I’m opposed to it… I see no reason why… they should be a permanent member on the Arctic Council”

Current permanent observers are Britain, France, the Netherlands, Poland and Spain. Since the EU, China, Italy, and South Korea are only ad-hoc observers, their presence must be re-accepted at each meeting.

News Links

Pan-Arctic Inuit council wants more say in sovereignty, Canada.com

Russia against increasing military presence in Arctic, RIA Novosti

Norway passed the chairmanship to Denmark.

Arctic Council rejects EU’s observer application, EUObserver