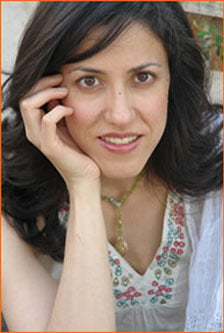

Azadeh Moaveni is a former Middle East correspondent for Time Magazine, The Los Angeles Times, and the Al-Ahram Weekly of Egypt. She has lived and reported throughout the Middle East. By the age of 23, Azadeh was reporting for the Time Magazine, a testament to her remarkable rise on the American journalism scene.

Born in California and currently living in London with her husband and son, Azadeh was one of the few American correspondents allowed to work continuously in Iran since 1999. She reported widely on Iran’s youth culture, women’s rights, and Islamic reform for Time, The New York Times Book Review, and The Washington Post. Fluent in both Persian and Arabic, Azadeh studied politics at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and received Fulbright Fellowship to Egypt.

Azadeh is author of three books and currently writing a novel set in contemporary Iran.

________________________________________________________

How long have you been in the journalism profession and what is your current line of work?

I started out as a journalist in Cairo back in 1999, working for the Cairo Times, the only independent news magazine being published at the time, and later at Al-Ahram Weekly, the English edition of the venerable, state-run Al-Ahram. I worked as a correspondent in the Middle East for most of the past decade, but as my career segued into book writing some years ago, I usually have a book project going on the side. Right now I’m freelancing for many different publications, and working on a short story collection set in present day Iran.

Were you born in Iran? How long did you live in Iran?

I was born in California and only visited Iran once as a child. I have only lived in Iran properly as an adult, probably for a total of about six years sprinkled across the last decade.

Tell us about your education please. Also, what led you to learn Arabic? I assume you speak Arabic fluently.

I was a politics major at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and then studied Arabic at the American University in Cairo on a Fulbright scholarship. I knew at university that I wanted to work in the Middle East and observe its politics up close, but in the late nineties Iran was still very much closed off, not the kind of place you could just show up looking for a summer internship. I felt intuitively even as a young person that I could never know Iran fully without deepening my experience of the Arab world, so I set off to Egypt to learn Arabic.

How did your path to journalism take its shape? What news media organizations have you worked for?

Journalism appealed to me even as a teenager on my high school newspaper; it just seemed like this incredible profession that enabled you to satisfy your curiosity about your surroundings and engage with the wider world.

After my start in Cairo working for local Egyptian newspapers, I moved to Iran in late 1999 as a stringer for Time Magazine. I started out covering Iran but the region seemed only to grow more turbulent, so I started helping out in Lebanon and Syria and usually tended the Cairo bureau in the summers. I eventually went on staff and worked for Time all around the region, covering Syria, Jordan, the Persian Gulf region and northern Iraq, although Iran was always my chief assignment.

When the U.S. went to war in Iraq, I wanted some daily newspaper experience and joined the Los Angeles Times (LAT). I worked for the LAT for about a year, mostly in Iraq, but a bit in Lebanon and Iran as well, until I left to write my book, “Lipstick Jihad.”

Who would you name among some of your main sources of inspiration in your journalistic achievements?

I was very lucky to get my start in journalism under Hisham Kassem, who ran the Cairo Times, the only independent news magazine in Egypt at the time. The Egyptian government controlled the press tightly, and Hisham was a master at pushing the boundaries; he managed to cover very sensitive subjects without getting his paper shut-down. What he could accomplish in that kind of lock-down atmosphere was terribly impressive, and prepared me – intellectually, ethically, and practically – for reporting in Iran.

I also met the Iranian AP correspondent Scheherezade Faramarzi in Cairo. Becoming Scheherezade’s friend and watching her work confirmed to me that I wanted nothing more than being a journalist. Scheherezade had covered the Lebanese civil war, the early years of the Iranian revolution, and she was my window onto what journalism can offer in the face of such conflicts: in the best cases, it can hold power to account, and correct history by calling the militiamen and politicians’ out on their lies. Schehrezade was the model for the type of journalist I wanted to become – emotionally and morally engaged with the story, fluent in the local language, and absolutely fearless.

In the course of your career as a woman working in major American news organizations, what have been some of the key challenges that you have encountered?

The greatest challenge for me was learning how much passion and personal principle it was feasible and appropriate to bring into my work. I began working for a major U.S. publication at a very young age; at 23 I was reporting for Time in Iran and Lebanon, basically on my own in the field filing stories back to New York. I didn’t have the chance to mature as a reporter by starting out in a newsroom, and I felt crushed that my stories weren’t able to reflect my views about Israel’s role in Lebanon, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, or the American habit of demonizing Iran. I remember weeping one night in the lobby of a Beirut hotel after seeing a story I contributed to go online, feeling like a sell-out; because I felt my reporting was being fed into this one-sided narrative of the conflict that I strongly disagreed with.

The way journalists deal with this problem is by developing clout within their organization over the years, so they can eventually push through unpopular or controversial stories by the force of their accumulated expertise. But the changing nature of the media has complicated this, as full-fledged staff foreign correspondents are few and far between these days, and media outlets have no responsibility to freelancers – they can just brush off the story ideas they don’t like, or don’t have the patience to see through the controversy.

How would you characterize the challenges of reporting from Iran as a female journalist? Do you think they were all political and ideological, or do you think cultural factors were also at play?

That’s an interesting question; I suppose with modern Iran it’s so tough to untangle the political and the cultural. Most of the difficulties I faced came from the patriarchal attitudes and sometimes downright misogyny that are part of Iranian culture. But of course the revolution’s religious agenda and treatment of women has only nurtured and compounded all of that. The government has created an atmosphere whereby men can easily and without much consequence treat women like garbage in public. But to be honest, I see the same kinds of attitudes in the Iranian diaspora. I see it in how Iranian monarchist men who disagree with my views attack me on Twitter, or even the discourse that prominent Iranian male academics use to disparage Iranian women they disagree with – there is a very crude, “shut-up-bitch” type of aggression at work, and that’s part of the Iranian culture, whether in some stuffy government office in Tehran or the halls of Manhattan and Washington.

Would you say that being an Iranian woman or a woman of Iranian descent played itself out in your career in a significant way? If so, could you elaborate on it?

For me, being an Iranian woman was either a total liability or a great asset. In Iran itself, I was never treated with the grudging respect the government offers Western women, which means I had to deal with the real fears, humiliations, and ridiculous contradictions that only an Iranian woman would face: being forced to meet with intelligence agents alone in hotel rooms, but on other occasions told I couldn’t attend, say, a Hamas press conference because it was being held in a hotel room, and Iranian women are not permitted in hotel rooms!

But being an Iranian woman has also been invaluable to my work. It’s given me a different perspective on the places I was covering, and drawn me to stories about how conflict and politics affect daily life and social interaction. As an Iranian woman living in Iran, I experienced life as a citizen first, and that first-hand immersion was led me to write a book like “Lipstick Jihad.”

Speaking of Jihad, you have written three books: “Honeymoon in Tehran”, “Lipstick Jihad”, and “Iran Awakening”; the latter co-authored with the noble laureate, Shirin Ebadi. Can you tell us about the inspiration behind each of these books?

My first book, “Lipstick Jihad,” was inspired by my sense that the West, particularly America, had a hateful and clichéd view of Iranian society – it had no sense of Iran’s sophisticated and educated women, its culture of youth rebellion, its rich music and film industry, all of which reflected a society striving to do its noble, creative best. The prejudices from the movie “Not Without My Daughter” still ruled when I began my career, and I felt like all the news features in the world wouldn’t be enough to change this. So I felt I had to capture it all in a book, ideally one with a flashy title that would jolt Americans into seeing Iran differently.

If “Lipstick Jihad”was about teenage rebellion in Iran, I wanted “Honeymoon in Tehran“ to take a more sober look at what these Iranians dealt with as they matured. How they fared finding jobs, trying to get married, starting families. It is a less adventurous, winsome story in many ways, a darker book, but one that reflects the darker reality that the young generation faces growing older in Iran.

“Iran Awakening“ is of course Dr. Shirin Ebadi’s story, which is in many ways Iran’s story. I found her experience especially poignant and illuminating because of her background as a believing Muslim who supported the revolution, who believed that Islam was democratic, and then found herself robbed of her position and future. That kind of story helps us understand why so many Iranians are disillusioned with the revolution; it conveys a wider reality than the accounts of secular Iranian women who suffered under the new regime.

Are you a mother?

Yes, I am. I have two boys; Hourmazd, five, and Siavash, two.

How do you think the Arab Spring will impact women’s social status in the Arab/Islamic world? Are you an optimist?

I suppose I’m the conventional Middle Eastern pessoptimist on this question. I find the young Tahrir activists incredibly naïve and idealistic about the future, they seem so unprepared for how to respond to the Islamists’ better organization and so willing to give the Islamists the benefit of the doubt. In places like Tunisia, this kind of patience seems intelligent, but if I were a woman in Egypt I would be alarmed about the future. The Salafis’ success in the last election spells trouble; the harassment of the Copts seems a bad omen as well. Islamists who tolerate religious minorities can’t tolerate modern, empowered women either. But on the other hand, perhaps the Arab world needs to experience this moment, just as Iran did. The Islamists must be permitted to show their true colors, to build their ideal society, and Arab women can decide if it suits them.