Could We Create A New Version?

Russia is exploring settlement of trade payments in renminbi (China’s external currency). U.S. sanctions on Cuba may require sanctions on Venezuela to remain viable. And sanctions on Iran and Sudan led to criminal prosecution of BNP Paribas, and a spat with France.

Policymakers may understand that military power is finite, but they seem to think American economic, trade and financial power is more elastic. We do have great power in this arena, just as we do in the military realm. However, as the examples suggest, sanctions beget countermoves by their targets, necessitating further sanctions to remain effective.

This self-escalating dynamic can put us at odds with friendly countries, as in the BNP case. France, for all its idiosyncrasies, is a democracy with a culture of freedom and a NATO ally. French policies sometimes clash with America’s, but the complaints are of a family nature. If we look to appease countries like Russia and China while stumbling into spats with our friends, we risk alienating friends without gaining respect from others. In a world where values play a growing role in international relations, we should make our deepest affinities clear.

Poorly deployed sanctions also push targeted countries counter them. Russia is pushing back on U.S. moves to isolate them in the wake of the Ukraine crisis, by seeking to settle trade payments in renminbi. While this idea may not work, it shows how sanctions can motivate other powers to undermine American strengths — in this case, by developing an alternative global reserve currency.

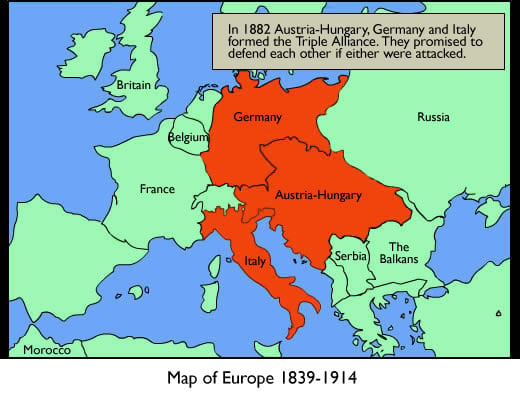

Sanctions that beget sanctions lead us toward a world of blocs that are not only geostrategic but also economic in nature. The U.S. Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) comes off as an economic alignment of nations at odds with China. The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Principles (TTIP) just about encompasses the U.S. and the EU, which leaves Russia, and perhaps Turkey, to their own devices. Blocs that base their commonality on economic as well as security ties will make outsiders more likely to become adversaries. In a world of such blocs, a Russian-Chinese pole might also counter the West’s liberal ideology with a shared doctrine of their own, perhaps one that qualifies the value of human liberties for the sake of order. Current dysfunctions in the U.S. and Europe may support this case.

A world where geopolitical control over trade and exchange is the norm will see less open development. Weaker countries will have to choose first where their political interests lie. Many will configure their domestic economies accordingly, often corruptly, and always economically sub-optimally. The growth of enterprise, and its attendant prosperity, will be circumscribed. The freedom fueled by developments such as cellphones in Africa, markets in China, and deregulation in Brazil, will become sparser and scarcer. Such development in recent decades has pointed more people toward freedom, and an appreciation of the tenets reflected in America’s Declaration of Independence. Its recession, especially if triggered by American sanctions, will reduce the stature of those tenets in hearts and minds around the world.

Sanctions have their place and their purpose. They can isolate a rogue from the mainstream of flourishing societies – if those societies form the world’s mainstream. But economic sanctions have a slippery slope character. If they lead international discourse to view trade, finance, and aid as weapons for competition rather than tools for shared growth, the world can become inhospitable to American values. The use of economic power requires a guiding ethos and strategy akin to the doctrines and disciplines we follow in the use of military force.