Gone are the heady heroin nights of the nineties, and with them, many of the expats who had come East to trade in the drudgery of their suburban lives for a more visceral, tragic version of humanity.

Now that the country brims with the Toyota Priuses (Prii? Priux?), hipsters, libel laws, Time Out Magazine, nuclear families, decent sushi and the other assorted petit bourgeois nightmares of back home, what's the point of putting up with a scary government and summary bureaucracy?

Indeed, to witness non-oligarchs holidaying abroad, taking up sales and marketing jobs and driving new model Ladas or even Peugeots can be very bittersweet. No matter how clichéd, the question begs asking: has the well-adjusted middle class life that has enriched the hitherto threadbare existence of so many (though still not even remotely the majority of) Russians cost us that self-destructive, protean, brooding, extremist yet spiritual truth seeking poetry – borne of suffering, longing, deception and isolation?

Has Russia lost, in a wordits SOUL??!

More chillingly, has said Soul been sold to a rentier state whose petrodollars drown questions of illegitimacy and oppression in the warm, moist umbilical fluid of light sweet crude?

Not quite! And here's why:

1. The 90s Paradox:

The libertinism of moral clarity and/or cheap drugs, anarchy and play that the expat rebels revelled in proved catastrophic for their Russia's own Rimbauds.

In fact, the Soviet enfants terribles of the 1980s: young guys trapped in obscure think tanks penning underground verse or music, hippies and political dissidents who shocked and shamed their bankrupt system in the same way that the Exile shamed and shocked its own, could not survive in the new climate.

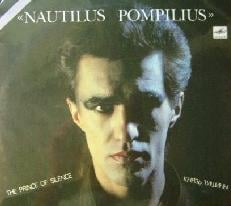

Their rock music , filigreed, cryptic and high maintenance – didn't stand a chance against Aerosmith or the Spice Girls. In a country drowning its collective sorrow in endless re-runs of Santa Barbara and The Bold and the Beautiful, no-one had the time or money for their now-permitted protest literature. Their well paying research jobs, at which they could comfortably sit and write, disappeared. Many sold out; for others, despair and the dulling embrace of heroin replaced the creative kick of vodka and kombucha tea.

By the end of the 1990s, the Soviet intellectual, dissident and underground scene effectively disappeared. In 1998, Claude Frioux had written its obituary in Le Monde Diplomatique:

Russia's intellectuals are now entirely absorbed with questions of material survival, paralysed by a fear of displeasing somebody, and confused about how to deal with the mafia face of power….They are no longer the small islands of lucid dignity that they once were. They are now an amorphous mass, and outside observers comment dismissively on their cynical lack of concern and their total absorption in the business of making ends meet.

Even in Russia, people sitting in unheated flats and using furniture for firewood eventually switched from questions of philosophy to questions of finding scraps of food; undoubtedly in an homage to Bakhtin.

2. Biting the Hand that Feeds You:

A cursory look at instances of mass intellectual awakening/rebellion reveals that such events generally follow periods of increased material wealth and stability. 1968 is the obvious example. In Russia, it was no different. The impoverished and hellish 1930s and 40s gave way to the staid, authoritarian and materialistic 1950s. Yet before the decade was out, Khruschev's famous Thaw began. Similarly, the wealthy, even ‘decadent’ years of Brezhnev's stagnation (few in the West realise that Soviet living standards peaked in the mid 1970s, and that it was the time of every baby boomer's life) preceded the grass roots rebellions of the late 1970s and early 80s that eventually paved the way for Gorbachev's glasnost.

History shows that as soon as (but not a moment before) a country raises a generation of reasonably well fed, educated young people in an ordered, stable society, they will immediately proceed to do their best to undermine and destroy that society, tear up its sick, fraudulent and oppressive underbelly, and seek freedom. Before long, they will become bankrupt and bitter or ‘grown up’ and responsible, and the cycle will continue.

Thus, is it any surprise that after a decade of abject poverty and national trauma beginning in the late 1980s, Russia now witnesses an era of a materially comfortable, socially conservative authoritarianism?

Indeed, it would be useful to keep in mind an article by Other Russia leader Eduard Limonov that appeared in today's Grani.ru newspaper.

In it, he writes that Putin's authoritarian system will be overturned not by the impoverished masses, but by a growing wave of educated disaffected youth feeling stifled and demanding philosophical rather than material freedom. Thus, unlike with the masses, the regime's capacity for delivering the goods economically would no longer be enough to save it.

So where is this new ‘class for itself’, these islands of lucid dignity? We don't hear much about them in the West, but they are definitely out there. In the field, one group is Limonov's own National Bolshevik Party foot soldiers, frequently arrested on trumped up sedition charges, and even occasionally killed. On the intellectual front, someone to watch is Kirill Medvedev, a young dissident writer, poet, activist and blogger whose work has recently been profiled by the dashing Russian-American factotum and animal lover Keith Gessen in his own thick journal n+1. What kinds of things can we expect from this new generation? Well, a recent essay posted on Medvedev's site quotes the following poem:

Literature Will Be Tested

—

Entire literatures consisting of subtle turns of phrase

will be tested to prove

that where there was oppression,

there were also rebellions.

By the prayers of earthly creatures to heavenly beings

it will be shown that the early creatures trampled one another.

Their rarefied verbal music will testify

that many did not have enough to eat.

Don't write off Medvedev's Russia quite yet.