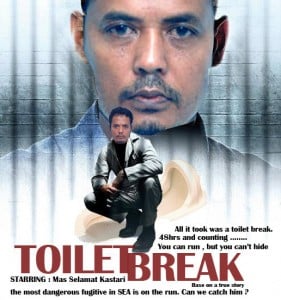

Mas Selamat bin Kastari, a high ranking leader of Jemaah Islamiyah, is in Malay custody. He was recaptured more than a year after he escaped, pantsless, through the bathroom window of the Whitley Road Detention Center in Singapore. His recapture has resulted in much celebration among the Malaysian and Singaporean security industries, though it has been mostly overlooked by the Western media. It’s important for us to understand the history of Jemaah Islamiyah as part of the ongoing security struggle with terrorism in the security states of Southeast Asia.

Mas Selamat bin Kastari, a high ranking leader of Jemaah Islamiyah, is in Malay custody. He was recaptured more than a year after he escaped, pantsless, through the bathroom window of the Whitley Road Detention Center in Singapore. His recapture has resulted in much celebration among the Malaysian and Singaporean security industries, though it has been mostly overlooked by the Western media. It’s important for us to understand the history of Jemaah Islamiyah as part of the ongoing security struggle with terrorism in the security states of Southeast Asia.

There are more than 260 million Muslims in Southeast Asia, with the vast majority in Indonesia and Malaysia. Both countries have been spotlighted repeatedly for corruption, ethno-religious discrimination, and human rights abuses. Though nominally Muslim countries, there are many who feel that they are oppressive and overly obsequious to the west. As we have seen over and over again across the world, oppressive governments which are seen as morally and religiously bankrupt by their citizens are the perfect breeding ground for fundamentalist terrorist groups.

It was out of this climate that Jemaah Islamiyah was born. With the nominal goal of a unified Southeast Asian Islamic state ruled by strict Sharia law, they grew a substantial support base among the poor and disenfranchised in the region. In the 1980s, members of JI heeded the call of international Jihad and traveled to Afghanistan to fight with the Mujahedeen against the Soviet invasion. There they made connections with similar organizations from as far afield as Chechnya, Kashmir, Uzbekistan, as well as the large and extremely well organized Maktab al-Khadamat, Osama Bin Laden’s organization which was the forerunner to al-Qaeda.

Radicalized by their experiences in Afghanistan, members of JI returned to Southeast Asia where they continued to publish conservative theological literature and open religious schools dedicated to strict Islamic practices, and they provided succor to al-Qaeda in the region. They organized themselves into cells, and built ties with a variety of other Islamic separatist and nationalist organizations throughout the region. They did not, however, begin engaging in outright terrorism until the year 2000.

Since 2000, JI has been involved in over a dozen terrorist attacks, the largest of which was the Bali nightclub bombing in 2002, which killed more than 200 people. They have been demonstrably active in Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Singapore, the Philippines, and Australia.

The arrest of Selamat is not a particularly significant victory for regional security forces so much as his initial escape was a crushing defeat. Singapore is a predominantly Buddhist city-state with 5 million people living in it. It has the fifth highest GDP per capita in the world, and spends nearly a third of its GDP on military and security. With only about 15% of its population practicing Islam, the fact that JI has a presence in the country at all is a testament to the organization’s power. But that Singapore’s Most Wanted managed to jump out a bathroom window sans-culottes, swim across a river in broad daylight and then evade capture for a year and a half in neighboring Malaysia shows just how difficult nation-states are finding the prosecution of international terrorists.

With all eyes on Pakistan and Afghanistan, it is important to remember the lessons of Mas Salemat and JI. Terrorism is a global problem. It is a product of institutional weaknesses around the globe, and exists on a truly transnational scale. And, most troublingly, it is a problem that national governments around the world have found nearly impossible to deal with in a timely and effective manner.