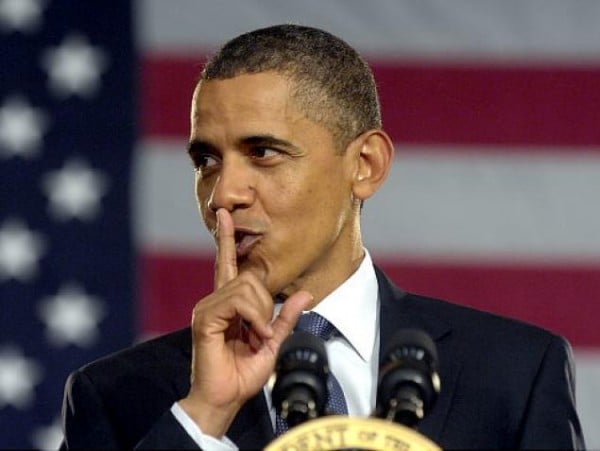

Photo Credit: HERTZBERG/AP

North Korea’s nuclear test this week, coming on the heels of last December’s launch of a long-range ballistic missile along with reports (here and here) that Pyongyang is developing a mobile missile launcher, underscores a point I’ve argued in earlier posts (here and here): It is exceedingly difficult for Washington to stop a rogue regime determined to develop nuclear weapon capabilities, especially if it located in a strategic part of the world, has powerful patrons, and is able to inflict retribution on important U.S. interests in the region. This lesson is all the more poignant given the Obama administration’s contention that its policy of strategic patience actually represents a harder line vis-à-vis North Korea than what the George W. Bush administration pursued. It also is one that gives Iranian leaders all the more reason to discount Mr. Obama’s tough talk regarding their own nuclear ambitions.*

Not that the president’s deliberately ambiguous words about “all options are on the table” vis-à-vis Iran had much credibility to begin with. After all, his insistence that he is prepared, if necessary, to use military force to stop the country’s nuclear program is constantly undercut by his determination to wind down U.S. military involvement in the greater Middle East as well as his rhetoric about the overriding urgency of the domestic agenda.

The disconnect was plainly evident in this week’s State of the Union address, with its heavy focus on domestic issues. In the cursory passages Mr. Obama devoted to foreign policy, he vowed to “do what is necessary to prevent [Tehran] from getting a nuclear weapon” but also emphasized that he was bringing “a decade of grinding war” to an end. And this follows last month’s inaugural address in which he declared that “a decade of war is now ending” and warned against “perpetual war.” As one foreign policy commentator puts it, Mr. Obama, who started his presidency pledging to fight a “war of necessity” in Afghanistan, has evolved into the “extricator in chief.”

Further evidence of this proposition comes from the president’s wary approach toward the Syrian civil war. According to media reports (here and here), wariness of becoming entangled in the growing crisis led the White House this past summer to veto plans to arm the Syrian resistance that were being pushed by much of the administration’s national security team: Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton; Defense Secretary Leon E. Panetta, CIA director David Petreaus, and General Martin E. Dempsey, the Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman. A similar caution prompted the minimalist “leading from behind” posture on Libya in 2011.

Mr. Obama’s new Cabinet appointments, especially of Chuck Hagel as Pentagon chief, reinforce the contradictory message on Iran. The Washington Post’s Bob Woodward reports that Obama selected Hagel due to the similarity in their worldviews. This philosophy, Woodward sums up, believes that:

the U.S. role in the world must be carefully scaled back — this is not a matter of choice but of facing reality; the military needs to be treated with deep skepticism; lots of strategic military and foreign policy thinking is out of date; and quagmires like Afghanistan should be avoided.

The bottom line: The United States must get out of these massive land wars — Iraq and Afghanistan — and, if possible, avoid future large-scale war.

Although Mr. Hagel now says that he is on board with the president’s stated policy on Iran, he has expressed prominent opposition to its major tenets in the past, particularly regarding the feasibility of military action (examples here and here). It’s true that Mr. Obama’s other defense secretaries, Robert Gates and Leon E. Panetta, have uttered similar cautions. Still, Hagel’s past objections are so stark that it raises major questions about the president’s actual position. As one Middle East expert notes, Hagel’s appointment

almost certainly raises doubts among allies and adversaries alike that Obama may not be nearly so committed to using all means necessary to prevent Iran from achieving a nuclear weapon as he pledged during his reelection campaign.

And it seems fair to say that these doubts were only deepened by Hagel’s embarrassing stumble during his Senate confirmation hearing in articulating the administration’s stance on whether a nuclear-armed Iran could be safely contained.

Of course, a desperate Israel could decide to launch a unilateral military strike on Iranian nuclear facilities that then sparks a broader conflict that embroils the United States. In his new memoir of his service as the White House point person on the Middle East, Elliot Abrams relates an interesting tale of how the Israelis acted on their own in September 2007 to destroy a Syrian nuclear reactor – that was being built with North Korean assistance – after the Bush administration decided to opt for diplomacy.

A similar scenario cannot be ruled out today. But when it comes to embarking upon a premeditated military action of his own, my bet is that Mr. Obama will accept a nuclear-armed Iran as a fait accompli rather than resort to arms to prevent it. As Edward Luce at the Financial Times noted the other month:

Those who know Mr Obama best find it hard to imagine that in practice he would exercise the military option to which he has implicitly committed himself. If a US attack on Iran went wrong, or events went out of control, it could wreck everything else on his agenda, including the US economic recovery. It could also ruin attempts to stabilise Syria and hopes of nudging President Mohamed Morsi’s Egypt in a semi-democratic direction. Not to mention what remains of unity in Iraq and Afghanistan. Or the pivot to Asia.

*Both proliferation threats may be converging. As the New York Times reports,

The Iranians are also pursuing uranium enrichment, and one senior American official said two weeks ago that “it’s very possible that the North Koreans are testing for two countries.” Some believe that the country may have been planning two simultaneous tests, but it could take time to sort out the data.

This commentary was originally posted on Monsters Abroad. I invite you to connect with me via Facebook and Twitter.