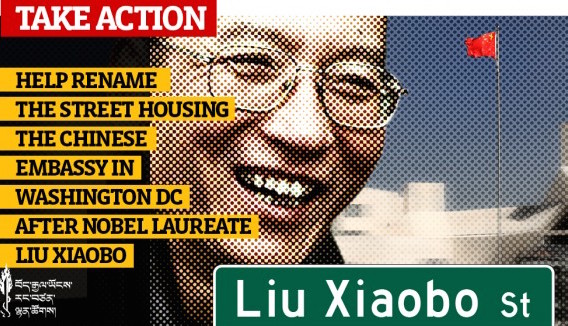

In February, the U.S. Senate unanimously passed a bill to rename the street in front of the Chinese embassy “Liu Xiaobo Plaza” in honor of the imprisoned Chinese dissident and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. A companion bill was introduced in the House of Representatives and awaits further action. Like Soviet-era Russian dissident scientist Andrei Sakharov, who was so honored on the street in front of the Soviet embassy in the 1980s, Liu would be a most deserving recipient of such an honor. Like the former Soviet Union, the People’s Republic of China would also deserve the embarrassment for its atrocious record of human rights abuse.

Unfortunately, the White House has signaled that it would veto the bill in deference to China and to the U.S.-China business interests that lobby Washington on China’s behalf. Beijing reacted with rage when the bill passed the Senate and threatened “serious consequences” if the street in front of its embassy were to be so renamed. Meanwhile, Liu Xiaobo remains in prison as the worst human rights crackdown since Tiananmen continues under China’s current leadership headed by President Xi Jinping.

Liu Xiaobo (PEN America)

A push to rename the street in front of China’s embassy after Liu seems to be a fight worth waging. Most importantly, as the Washington Post editorial board has argued, it is simply “the right thing to do.” When it comes to Western kowtowing to Chinese dictators at the behest of China business interests, the U.S. government and the Obama administration are far from the worst. The worst would probably be the British government under Prime Minister David Cameron, which seems determined to turn the United Kingdom into an overseas possession of the People’s Republic of China at whatever price Beijing is willing to offer. The U.S. at least offers “statements of concern” on China’s bad behavior for Beijing to disregard as its behavior grows worse and worse.

Somewhere in Beijing, a framed collection of “statements of concern” from Washington probably hangs on a wall for Chinese officials to poke fun at as they toast each other with glasses of Moutai and draw up plans for turning Western capitals into Chinese theme parks. They didn’t laugh, however, when the Senate unanimously passed bill S.2451 to rename the street in front of their Washington embassy after Liu Xiaobo. They were “furious,” and “demanded the United States veto a motion that would see a plaza in front of the Chinese embassy in Washington D.C. renamed after convicted criminal Liu Xiaobo.”

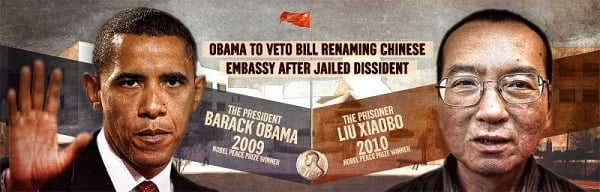

The White House quickly made it all better for them, however, by showing that Chinese money is more of a priority than democracy and human rights. This must have been soothing news, too, for the China business lobby, loathe as it is to see its apple cart in China upset over such trifling matters as imprisoned dissidents. It wasn’t such good news for China human rights activists, as a graphic from the Laogai Research Foundation clearly shows, noting Liu’s and President Obama’s shared (though not yet equally earned) status as Nobel Peace Prize laureates:

Obama to veto Liu Xiaobo Plaza (Laogai Research Foundation)

In addition to the Laogai Research Foundation, “Liu Xiaobo Plaza” has won the support of activists Garry Kasparov of the Human Rights Foundation and David Keyes of Advancing Human Rights. “Every crack counts,” said Keyes on the renaming of streets in front of embassies after dissidents like Sakharov and Liu as a human rights tactic, “Each time I annoy a dictatorial regime a little bit, it is another crack, and then another.”

It’s also high time that the China business lobby and other “China accommodationists” got knocked down at least a peg or two, and high time that human rights stopped getting sent to the kids’ table while the “grown-ups” talk about trade. Making “Liu Xiaobo Plaza” the Chinese embassy’s new address could be at least a small step toward turning “statements of concern” into real consequences for Beijing’s bad behavior.

Furthermore, it is a fight that human rights activists could conceivably actually win, particularly in an election season when no one running for election or re-election wants to appear “soft on China.” To wage a fight for “Liu Xiaobo Plaza” and to win, through cold, hard political tactics, could send a clear signal to Beijing and its U.S. accommodationists that the China human rights community is not going to play nice and be ignored anymore.

As noted, the Senate bill for “Liu Xiaobo Plaza” passed unanimously. Given sufficient public attention and public pressure, the House bill (H.R.4452) could likewise pass at least by a wide margin if not unanimously, and even the White House might be persuaded simply to do the right thing and sign it into law. Otherwise, sufficient votes might be raised from House members seeking re-election to do the right thing and override a White House veto. In either event, the Chinese embassy could soon find that its new address is One Liu Xiaobo Plaza, Washington DC 20008.