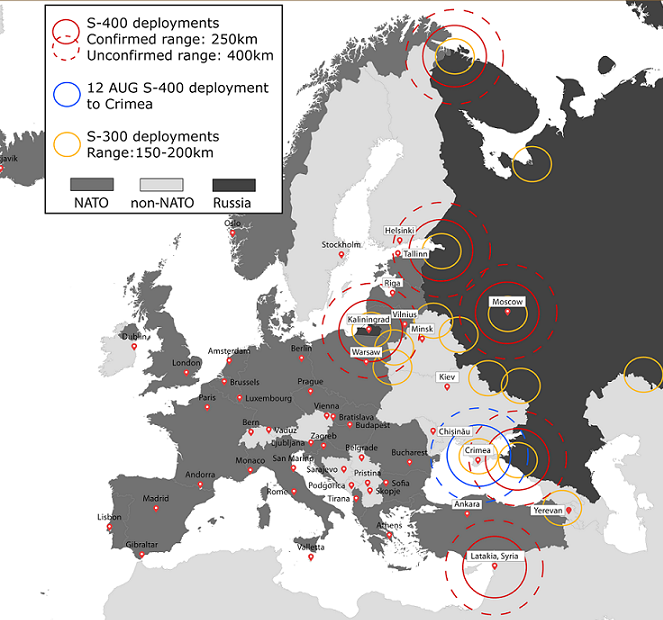

Russian A2/AD Range: August 2016. (Institute for the Study of War)

The information and views set out in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the NATO Parliamentary Assembly.

In response to NATO’s unmatched ability to conduct large-scale airspace operations, Russia has established large anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) exclusion zones or “bubbles” around the Baltic states, the Black Sea, the Eastern Mediterranean and the Arctic. These A2/AD bubbles allow Moscow to deny the use of the airspace in these areas and dramatically constraint the movement of ships and land forces in case of a crisis.

In the Warsaw communiqué, NATO expressed its concerns over these developments, declaring that it would not accept having the freedom of movement of Allied forces constrained by any potential adversary. Russia’s A2/AD exclusion zones can be geographically broken down as such:

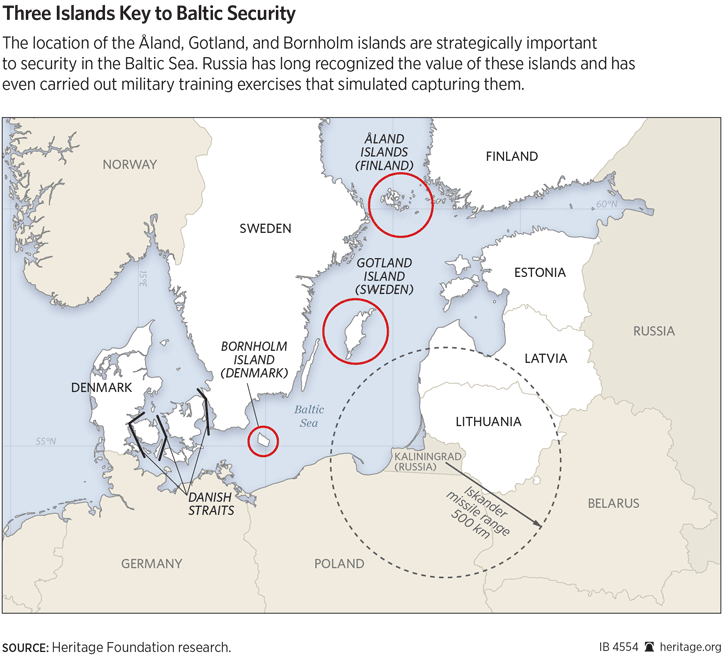

The Baltic region is where Russia poses the greatest challenge to NATO, particularly to Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Poland. NATO’s small footprint in the region and the geographic isolation of the Baltic States accentuate this threat. The Suwalki gap, located along the Polish-Lithuanian border, is vulnerable to Russian shelling or invasion from Kaliningrad and Belarus in the event of a conflict—making overland reinforcement difficult. Because NATO lacks significant pre-positioned stocks and forward deployed forces east of Germany, the Russian build-up of A2/AD capabilities in its Western Military District, Kaliningrad, Belarus, and the Baltic Sea presents a challenge to reinforcing the Baltic States quickly enough to prevent a rapid Russian victory.

The missing piece in Russia A2/AD bubble in the Baltic region is the Swedish island of Gotland. If anti-access capabilities were deployed on the island, they would severely constraint Moscow’s ability to impose an area denial bubble over the region. In turn, this would prevent Russia from closing off the Baltic countries from the rest of the Alliance—a crucial reason for NATO to further its partnership with Sweden.

While relatively vulnerable itself, Kaliningrad is heavily militarized. As for A2/AD capabilities, the exclave hosts coastal radars that can connect to K-300P Bastion-P shore-based mobile anti-ship missile batteries, which launch Mach 2.5+ supersonic sea-skimming P-800 Oniks missiles. Additionally, Kaliningrad hosts the S-400 Triumf and the SA-21 Growler, which has an operational range of 400km. Further defended with Pantsir-S gun-missiles, Kaliningrad’s offensive weapons effectively render large amounts of the Lithuanian and Polish airspace de facto no-fly zones for conventional non-stealthy aircraft.

Although Russia has, in two previous occasions, temporarily placed the 500km-range, nuclear-capable Iskander missile in Kaliningrad, officials now say the missile will be deployed there permanently by 2019. They argue this decision is in response to the U.S.-supplied NATO Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) capability under development in Romania and Poland. Should NATO wish to build up its capacity to more quickly overcome this A2/AD bubble, the Alliance would require additional forward deployments of forces and equipment.

In the Black Sea Region, Russia deployed a shore-based Bastion-P anti-ship missile system on the Crimean peninsula, equipped with P-800 Oniks missiles and S-300 PMU anti-aircraft missile systems, all connected to coastal radars. Soon afterward, Moscow announced the deployment of Tu-22M3 Backfire bombers, Tupolev Tu-142 and Ilyushin Il-38 maritime patrol and anti-submarine aircraft. The Tu-22M3 uses as many as 10 Raduga Kh-15 missiles or up to three Raduga Kh-22 missiles, which are designed to defeat advanced air defense systems and may carry nuclear warheads. Deployment has ostensibly begun, but not all sites are prepared for these installations. In addition, on August 2016, Russia deployed S-400 missile systems to Crimea, furthering the militarization of the peninsula. Reinforcing its hold, Russia also has S-300 missile systems deployed at its 102nd military base in Armenia, extending A2/AD capabilities over the eastern Black Sea, Georgia, and eastern Turkey.

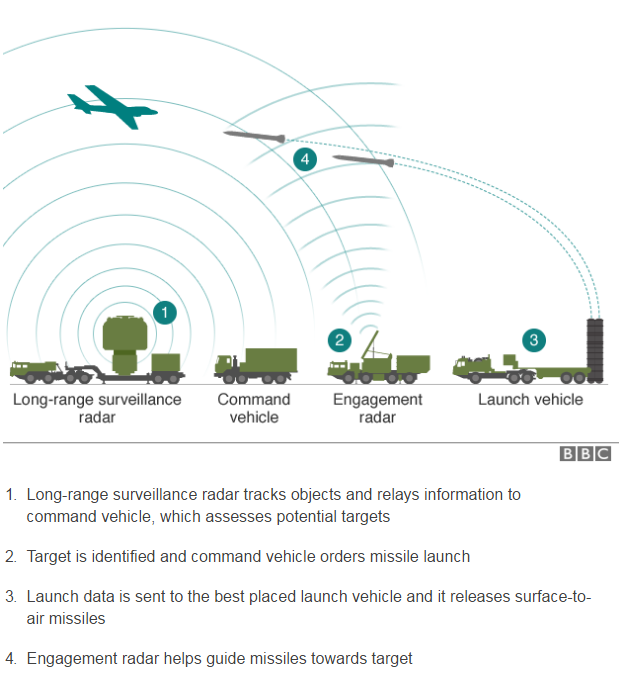

How the S-400 Air Defense System Works

Russia plans on spending $2.3 billion on the Black Sea Fleet by 2020, and 80 new vessels should join the fleet in that time. Despite delays, the current fleet maintains a strong A2/AD capacity through simple contact sea mines and land-based, air-launched, and submarine-based anti-ship cruise missiles. By 2018, the fleet should receive six new Admiral Grigorovich class and six new Vershavyanka class submarines. Meanwhile, the U.S. 6th Fleet based in Spain has just a single command ship and four destroyers as of 2015.

On the one hand, although the A2/AD bubble overlaps with Allied territory in Turkey, Bulgaria, and Romania, it would not prevent NATO from reinforcing these countries in an open conflict, as all three could be supplied by alternative routes. Thus, Russia’s Black Sea A2/AD has strong defensive capabilities and may politically intimidate Black Sea nations, but it does not threaten to eliminate regional NATO defenses.

On the other hand, there have been reports that Russia has placed, or intends to place, nuclear-capable Iskander missiles in Crimea. This is allegedly in response to the declaration of initial operational capability of NATO’s BMD facility in Deveselu, Romania—although the base is outside the official 500km range of the Iskander, if placed in Crimea. Should Russia choose to enhance the missile’s range to compensate, it would be in direct violation of the 1987 Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, banning all land-based ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500km.

In the Eastern Mediterranean, the Yakhont anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) deployed in Syria create a surface naval A2/AD bubble in the region. Moreover, the Khmeimim Air Base acquired S-400 missile systems after the 24 November downing of a Russian jet. There are also reports that Russia deployed at least one Iskander missile to Khmeimim in 2016, though it is unknown whether it is the ballistic or cruise missile version. In October 2016, S-300 air defense systems were delivered to the Tartus naval facility, allowing Russia to control most of the Eastern Mediterranean airspace.

Russia advances its Integrated Air Defense System (IADS) in Syria. (Institute for the Study of War).

Since the Black Sea Fleet has relatively easy access to Tartus during peacetime and Russia has already used its submarine-launched missiles against anti-Assad forces, the A2/AD bubble in Syria has demonstrated to be quite capable, particularly when compared to the minimal NATO maritime presence in the Mediterranean. However, in the event of a conflict, the zone would remain fairly vulnerable to Turkey, which could cut off supplies by closing the Straits. This makes Ankara’s relationship with NATO and Moscow particularly important for the future significance of Russia’s presence in the region.

Russia’s development of A2/AD capabilities in the Arctic is part of the larger initiative to restore its military capacity in the “High North.” In December 2015, Russian news reported the deployment of two S-400 long-range surface-to-air missile systems to Novaya Zemlya archipelago and to the Yakutian port of Tiksi, and additional reports indicate the presence of S-300 missiles on at Franz Joseph Land, New Siberian Islands, Novaya Zemlya, and Severnaya Zemlya. These sites are protected by Pantsir-S1 short-range mobile air defense systems, which are armed with Igla-S surface-to-air missile launchers and Djigit cannons. Additionally, Novaya Zemlya is equipped with Bastion-P complexes armed with P-800 Yakhont anti-ship cruise missiles.

Furthermore, new forward military bases helped reestablish radar coverage for the entire northern coast, a capability lost in the 1990s. As the Northern Fleet comprises approximately two-thirds of the Russian Navy, the Arctic theatre also contains permanent deployments of submarines and other maritime vessels with anti-ship and anti-aircraft capabilities, such as the Severodvinsk nuclear attack submarine.

For now, developments in this region are of secondary importance to the Alliance compared to similar force buildups in the Baltic region. But Allied countries assess the threat differently: Norway takes a stronger view and desires more NATO involvement, whereas Canada, while sharing Norway’s concern, would prefer to approach Arctic security outside of the NATO framework. Regardless, Russian forces in the region dwarf those of NATO members, including the United States, and neither the Wales nor Warsaw Summit communiqués named the Arctic as a priority.