So it seems the Obama administration has decided not to join the International Criminal Court (ICC), a decision that comes as no surprise. The news comes from Jurist, which reported last week about a talk given by the U.S. Ambassador-at-large for War Crimes Issues, Stephen Rapp:

Speaking at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, Rapp said that while the US has an important role in international criminal justice, it is unlikely to join the ICC anytime soon. Rapp cited fears that US officials would be unfairly prosecuted and the US’s strong national court system as reasons it would be difficult to overcome opposition to ratification.

The Obama administration began reviewing the U.S.’s ICC policy last year, living up to an Obama campaign promise. This promise, though, was always framed in a way that made rejection of the ICC seem inevitable. For example, here’s the Obama campaign’s 2008 stance on the ICC:

Now that it is operational, we are learning more and more about how the ICC functions. The Court has pursued charges only in cases of the most serious and systemic crimes and it is in America’s interests that these most heinous of criminals, like the perpetrators of the genocide in Darfur, are held accountable. These actions are a credit to the cause of justice and deserve full American support and cooperation. Yet the Court is still young, many questions remain unanswered about the ultimate scope of its activities, and it is premature to commit the U.S. to any course of action at this time.

The United States has more troops deployed overseas than any other nation and those forces are bearing a disproportionate share of the burden in the protecting Americans and preserving international security. Maximum protection for our servicemen and women should come with that increased exposure. Therefore, I will consult thoroughly with our military commanders and also examine the track record of the Court before reaching a decision on whether the U.S. should become a State Party to the ICC.

Though far from a glowing endorsement of the ICC, this position was a radical departure from that of Obama’s predecessor. President Bush officially renounced the Rome Statute (signed by Clinton in 2000) and signed the American Service-Members’ Protection Act (also known as the Hague Invasion Act), which grants the President the authority to use “all means necessary and appropriate to bring about the release of any US or allied personnel being detained or imprisoned by, on behalf of, or at the request of the International Criminal Court”. Obama’s position is a reversion to the Clinton policy of showing support for the court while not submitting to its jurisdiction (though Clinton signed the Rome Statute, he expressed “concerns about significant flaws in the treaty”).

The U.S. will likely show this support later this year by attending the ICC review conference in Uganda. The most significant topic on the conference’s agenda is the ICC’s ability to prosecute individuals for crimes of aggression. The ICC can currently prosecute individuals for crimes of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, but the Rome Statute’s Article 5 states of aggression:

The Court shall exercise jurisdiction over the crime of aggression once a provision is adopted in accordance with articles 121 and 123 defining the crime and setting out the conditions under which the Court shall exercise jurisdiction with respect to this crime. Such a provision shall be consistent with the relevant provisions of the Charter of the United Nations.

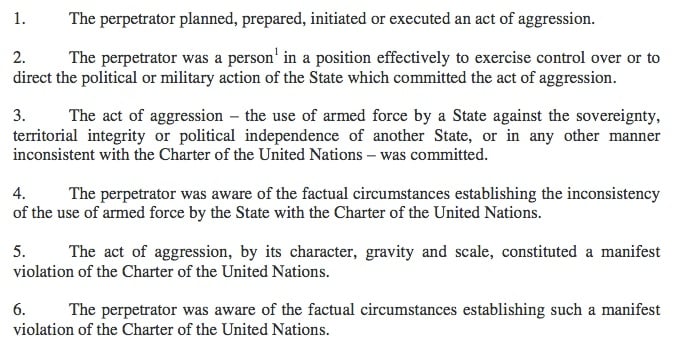

Thus the ICC’s ability to prosecute aggression hinges on the court’s ability to define the word. This is why the Assembly of States Parties, the ICC’s legislative body, established the Special Working Group on the Crime of Aggression in 2002. The Group’s Chairman wrote a “non-paper” last year taking a stab at the task (h/t to Kevin Jon Heller at Opinio Juris):

However, this endeavor, and the U.S.’s participation, even as an observer, is controversial. As Kenneth Anderson at Opinio Juris, argues:

One of the questions raised by the crime of aggression discussions among a group of states formed as a treaty-club is whether, and to what extent, the whole effort is a mechanism for “contracting around” the Security Council. Or, more precisely, contracting around the legitimacy of the Security Council. Ostensibly an exercise in private voluntary ordering … but simultaneously presenting a serious challenge, at least potentially, to the public regulatory ordering of the Security Council and its authority.

The Security Council, in practice, determines which uses of force violate the UN Charter. As I noted last year when discussing the legal controversies surrounding the U.S. entry into Afghanistan in 2001, this fact leads to strange conclusions. For example, Thomas Franck explained that if the Taliban deemed the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan illegal, the Taliban could simply “appeal to the Council to institute collective measures against its attacker under Chapter VII.” If the U.S., a veto-holding Security Council member, would be happy to deem its own military action illegal and participate in collective actions against itself, this solution might seem sensible. However, states don’t tend to behave that way. And there is no institutional check on the Security Council. The International Court of Justice takes the position that it cannot rule on the legality of Security Council resolutions. The General Assembly cannot pass binding resolutions. Thus, if the ICC gets into the aggression-defining and aggression-prosecuting business, it could alter the world’s international institutional landscape. This would be a good thing.