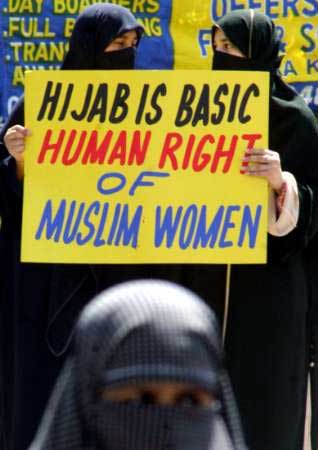

The legal and cultural battle of whether or not Muslims should be able to wear a headscarf, hijab, in educational or other government facilities has been a well-publicized, contentious debate in such places as Turkey and France, both either straddling or inside the West, but this issue is also starting to boil in parts of Central Asia. Abdumomun Mamaraimov and Saodat Asanova performed a thorough analysis of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan's own present controversy over the wearing of the hijab by school students.

It appears that in the last few years, the Tajik and Kyrg governments have moved in the direction of disallowing the wearing of hijabs in their government-run schools. Tajikistan's government has formally banned the practice and Kyrgyzstan's has done so more as a forced ‘recommendation.’ In any case, there are many citizens of the each state that feels this is a violation of their religious and individual rights. It appears that a few, though not an incredible amount, of female students have either chosen, along with their families in most cases, to stop attending school or have been suspended or expelled.

It appears that in the last few years, the Tajik and Kyrg governments have moved in the direction of disallowing the wearing of hijabs in their government-run schools. Tajikistan's government has formally banned the practice and Kyrgyzstan's has done so more as a forced ‘recommendation.’ In any case, there are many citizens of the each state that feels this is a violation of their religious and individual rights. It appears that a few, though not an incredible amount, of female students have either chosen, along with their families in most cases, to stop attending school or have been suspended or expelled.

While certain citizens are against this formal or informal ban, the government and education ministers claim it is a necessary measure against religious separation and extremism in a public sphere that the government desires to be secular. Tajik Education Minister Abdujabor Rahmonov equates the hijab with conducting ‘propaganda for religious ideas in a secular society.’ Both the Kyrg and Tajik government are most in fear of the Islamic group Hizb-ut-Tahrir, a group that advocates the non-violent removal of the region's secular governments with an Islamic state, but that has at times been connected to terrorist attacks. The leaders of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan do indeed have reason to fear radical Islamists as they have caused problems in the past for each state.

But this brings us to the central part of the hijab argument. It is obvious that most hijab wearers are just devout Muslims who mean no harm, but one cannot ignore that extremists do exist. So is the hijab ban slowing or strengthening extremism? Is the ban worth the loss of some religious and individual rights? The end of the Mamaraimov and Asaova piece attempts to answer these difficult questions. They rightly argue that the hijab cannot just be equated with Islamic extremism. If I wear a cowboy hat it does not mean I just got back from a rodeo. The two authors advocate a more nuanced approach to the conflict, though they don't offer any specific recommendations, except for those who feel they are being prosecuted because of their hijab wearing to be patient. The governments of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan need to communicate their reasoning for the ban. Their citizens need to know their voices are heard. At times, governments do need to make a law that punishes/restricts the many because of the wrongs of a few, but it is also the job of the government to clearly explain why such a law was passed. Unfortunately, the accountability I am discussing probably goes beyond what can be expected from these two governments. I also hold out hope that a compromise could be made, as in certain places in the school were the hijab is allowed or maybe just one day a week. Either way these two societies need to do whatever they can not to alienate or disenfranchise a portion of their populace as this policy is meant to discourage, not encourage extremism.