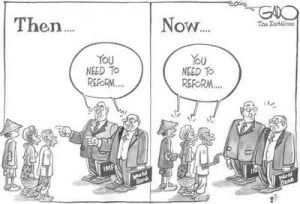

The Washington Consensus is dead. So what will replace it?

No one, including British economist John Williamson himself, could have predicted the viral-like application of one of his own political theories when he first introduced the term “Washington Consensus” in 1989. What was once simply applied to a grouping of commonly shared “policy instruments” used by Washington-based financial institutions like the IMF, World Bank and U.S Treasury, the term began to infect discussions on Latin American development as a political pandemic. Quickly though, fears of a global epidemic were spurred as the term and its application soon reached the Asian continent during the financial crisis of the 1990s. Soon heterodox economists, anti-globalization critics and politicians enraged with its prevalence began denouncing its existence in droves, in hopes that the proper attention, if given, to this bounding crisis of ideology would soon prevent it from swallowing the entire world. And as it found its way, mutated by neoliberal conversations of “market fundamentalism”, the perilous work of champion critics began to suppress its relevance as the fragile institutions that first supported its prominence began to crumble by swells of economic instability into the 2000s. Now, as the world is beginning to gain a foothold in the turmoil we’re currently facing, I can’t help but to question, is the U.S is still living in an age of neoliberal economic policy and trade relations?

Rather than a direct answer, I have instead found another question in Harvard professor Dani Rodrik’s, “Goodbye Washington Consensus, Hello Washington Confusion”: What will take the place of the Washington Consensus as the more prominent school of thought? And though I by no means have found a reasonable conclusion, I offer some color on recent events affecting US policy that I find to be of particular interest in this discussion.

The current state of the Washington Consensus

As I mentioned earlier, the “Washington Consensus” is a term originally coined by economist John Williamson to describe the commonly shared “policy instruments” of the Washington-based Bretton Woods Institutions and the Treasury Department in 1980s Latin American economic recovery. The Consensus, as written by Williamson, was a broad set of 10 recommendations for economic outcome in Latin America of “growth, low inflation, a viable balance of payments, and an equitable income distribution.” The following is a brief review of the 10 recommendations used by these institutions as Williamson described them in his 1992 paper, “What Washington Means by Policy Reform”:

1. Fiscal policy discipline

2. Policy reform with regard to public expenditure from subsidies toward education, health and infrastructure investment (especially to benefit the disadvantaged)

3. Increased taxes as a remedy to fiscal deficit

4. Market-determined, positive interest rates

5. Market-determined, competitive exchange rates

6. Import liberalization (i.e. anti-protectionist balance between export and import industries)

7. The promotion of Foreign Direct Investment with debt-equity swaps

8. Privatization of state enterprises and growth of private sector

9. Deregulation

10. Securing property rights

During the recent G-20 summit, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown echoed prevailing sentiments that the Consensus is dead, however, it appears as though its legacy lives on at least as an example of what not to do. I found a rather distressing testimony by Williamson as he discussed Washington’s 1980s economic objectives in Latin America in relation to some current issues of high national concern:

“Washington certainly has a number of other concerns in its relationship with its Latin neighbors (and, for that matter, with other countries) besides furthering their economic well-being. These include the promotion of democracy and human rights, suppression of the drug trade, preservation of the environment, and control of population growth. For better or worse, however, these broader objectives play little role in determining Washington’s attitude toward the economic policies it urges on Latin America. Limited sums of money may be offered to countries in return for specific acts to combat drugs, to save tropical forests, or (at least prior to the Reagan administration) to promote birth control, and sanctions may occasionally be imposed in support of democracy or human rights, but there is little perception that the policies discussed below have important implications for any of those objectives. Political Washington is also, of course, concerned about the strategic and commercial interests of the United States, but the general belief is that these are best furthered by prosperity in the Latin countries. The most obvious possible exception to this perceived harmony of interests concerns the US national interest in continued receipt of debt service from Latin America. Some (but not all) believe this consideration to have been important in motivating Washington’s support for policies of austerity in Latin America during the 1980s.”

Its taken 20 years and a new administration on the heels of a global economic downturn for Washington to begin giving serious attention to the fusion of economic interest with the relief of many of these social ills mentioned by Williamson. And yet, I find the most grave of consequences from the Washington Consensus to be more apparent in relation to growth and development in the Eastern hemisphere more than failures in the West. As the Washington Consensus was becoming more closely associated with neoliberal free market economics, “Chindian” economic policies began paving the way for the current wielding of financial prowess that these countries are starting to exercise in our own backyard.

The Beijing Consensus

At a time when the IMF and other similarly informed agencies were using the Washington Consensus as a reigning school of thought, China and India were producing sustainable economic growth with a paradoxical combination of reliance on market forces and “high levels of trade protection, minimal privatization, extensive industrial policies and lax fiscal and financial policies,” says Rodrik. Meanwhile employment of Washington Consensus type development was leading to disasterous implementation throughout Sub-Saharan Africa (with exception given to Uganda, Tanzania and Mozambique), short-lived success during the first-half of the 1990s in Latin America, and the eventual crash of Argentina in 2002. Today, instead of a prosperous Latin America, proudly touting the ideals of democratic freedom that “trickled down” from Washington, we see those same countries that worked in seemingly unconventional manners, lending financial aide to those who relied on the conventions provided by the Consensus.

I read in a recent article from the Washington Post (China Uses Global Crisis to Assert Its Influence) Chinese loan packages of $138 million to Jamaica made it the biggest financial partner to this small, Caribbean island. And while the numbers seem miniature, when compared to the amounts we’re currently spending on loans to some of our banks and other companies, it represents a flexing of economic potential previously unable to match the sheer strength of the U.S. In fear of sounding dramatic, China’s flexing of its economic muscle in U.S waters sends a clear message that its time to bury the already dead Washington Consensus. The article’s writer gave a nice thought to chew on with the following statement, “Chinese officials increasingly are challenging the primacy of the dollar, warning other countries about the danger of keeping reserves in just one or two currencies, such as dollars and euros. And as the global economic crisis has eroded faith in U.S.-style capitalism, there’s growing talk that a new ‘Beijing Consensus’ will replace the long-dominant Washington Consensus on how developing countries should manage their economies.”

So what’s to be done?

A New Role for the IMF

As recently as this past weekend, policy makers at the International Monetary Fund have begun to redress approaches to international lending in ways that will hopefully strip it from its legacy of its past 20 years. A new scope to the IMF will include more monitoring of the global economic system, including a review of the U.S financial system, while also granting new powers to countries like China, India and Brazil that previously had little influence at the Fund. The IMF will also act more like a global government banker with increasing flexibility to print its own money (based on the dollar, euro, yen and pound)and inject liquidity into global markets in ways previously held by central banks. To increase its lending capacity, it will also increasing funds through government pledges, and bond issuance.

Loans will be issued with a more pragmatic approach, moving away from harsh terms and enforcement of strict financial policies that became the hallmark of IMF lending, in an effort to “do away with procedures that have hampered dialogue with some countries, and prevented other countries from seeking financial assistance because of the perceived stigma in some regions of the world of being involved with the Fund.” This “modernization” as its being called, centers around two main enhancements to the practice of lending:

1. Focus on underlying objectives to a country’s structural reform program rather than enforcement of loan “conditionalities” of government reform. This focus of the IMF is in direct response to a 2007 IEO study that found “a significant number of structural conditions are very detailed and often felt to be intrusive and to undermine domestic ownership of programs.”

2. The creation of the Flexible Credit Line (FCL) which is a type of “insurance policy” for strong performing countries that have passed strict qualification criteria to have large and upfront access to Fund resources with no “ongoing conditions”. The FCL also includes a longer repayment period, no hard cap on access to Fund resources, and the ability to draw credit or use it as a precautionary instrument at any time.

Essentially, the IMF is hoping that by loosening its strict requirements and conditions associated with loans, not only will more countries look toward the Fund for its services, but will achieve the primary objective of economic development and relief. There couldn’t be a more apt time for the IMF to mitigate its intrusive and generic application of development principles. Hopefully, a less contentious environment for international aid will mean more successful and tailored approaches to development and create more space for the U.S to build on trade relations globally.

Can a new consensus in Washington be reached?

The new changes occurring in the IMF show signs of improvement for a new approach to international development and aide by the U.S, however, our first test will be in our restructuring of trade relations with many of our developing neighbors in the South. One of the biggest characteristics of the Washington Consensus approach to aide dealt with our ability to engage with countries of ideological and political leaning that were either different or in stark opposition to our own.

At the time of the term’s creation, the U.S was beginning to unwind itself from threat of nuclear war with Russia and a less tangible war with communist and socialist ideologies. The 47-year old trade embargo against Cuba represents the most ardent stronghold of the Washington Consensus, as full-out ideological warfare against the country has left little to no trade relations between our countries. With President Obama’s 13 April lift of sanctions against Cuba, this may serve as a litmus test for the U.S on repairing its approach to international aide in ways the Washington Consensus could not imagine. As it stands currently, the bulk of sanctions lifted by the President detail increases in travel for family members and remittances to Cuba. However, the President has also authorized U.S telecommunications companies to begin providing service and facilities to a population of approximately 12 million Cuban citizens for cell phone, internet, satellite radio and television. Currently, Venezuela has a monopoly on the Cuban communication industry, but with increasing access for U.S firms, information access for Cuban citizens may spur an organic spirit of economic competition and open doors for previously unrealized national development.

Beyond Cuba, the United States also currently maintains a symbiotic relationship to Mexico that, if developed judiciously, can result in new ways of strengthening bilateral ties that will improve conditions for both countries. While definitively holding off on re-negotiating NAFTA, President Obama did issue a new approach to security, energy and climate issues in a 16 April press release entitled “FACT SHEET: US-Mexico Discuss New Approach to Bilateral Relationship.” The President outlines specific plans for combating these issues including the Merida Initiative, arms trafficking, kingpin designation for cartels and a framework on clean energy and climate change. Click the following link to check out the President’s proposal, here.

So as the U.S fights to regain its once celebrated economic prowess, it will take an approach that compromises a strict enforcement of a “one-size-fits-all” model of American development for an unyielding pursuit of stable, global institutions that support the pursuits of the people. Hopefully, a new consensus in Washington can be reached that turns away from the mired Washington Consensus of the last 20 years and toward the original American consensus of the inalienable rights of all human beings for life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.