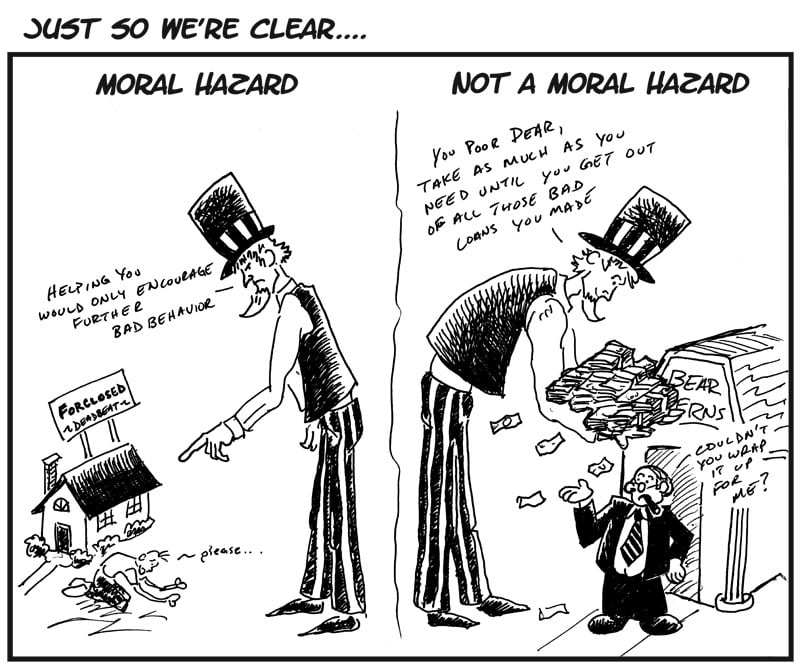

If taxpayers are expected to assume all the risk of bailouts there would be no market punishment for poor management, market inefficiency, corruption and bad risk management. It is already maddening that the same Wall Street oligarchs who precipitated the financial crisis earn hundreds of millions of dollars in base salary, bonuses and company stock options depsite losing billions upon billions of earnings on poor and reckless risk management. My argument against publicly financed bailout remedies is to allow tragic, but necessary, corporate failures such as the Enron, and the collapse of Bear Stearns is that this would change the incentives such that institutions and their managers may realize that the costs of risks they take will not be borne by the government or taxpayers, accordingly, they would be more prudent in taking systemic risks. Therein lies the problem: sometimes failure, as in life’s ups and downs, can be a useful tool on the road to success and more efficient markets. Companies such as Citibank, Bank of America and GM should be allowed to fail or put into receivership (i.e., ‘nationalization‘) instead of continuing in a state of functional insolvency. Capitalism, afterall, is risky business. There will be winners and losers.

The problem of moral hazard also affects government programs that insure people against misfortune. A variety of programs help people who suffer the misfortune of poverty. Aid to dependent children helps people who suffer the misfortune of having children to raise that they cannot financially support. Unemployment compensation pays people who suffer the misfortune of losing their jobs. Food stamps and public housing help the poor. Yet all these programs also suffer from problems of moral hazard. They increase children born out of wedlock, unemployment, and poverty. In the case of companies, or Markets, the existence of the government safety net (i.e., taxpayer funded bailouts) encourages unseemly greed and recklessly risky behavior by, and within companies. Some companies that become too big and central to the financial system — such as AIG or Citibank, for instance — regulators and policymakers using government funded programs will not allow them to fail.

The Moral Hazard dilemma of financial companies

Ironically, it is corporate executives — often the most conservative adherents of less government, personal responsibility for individuals; and of “free-market” orthodoxy — who are now the most dependent on the government teat; and choose to re-label corporate welfare, as “moral hazard.”

Moral hazard arises because of unethical, misguided or poor risk management by senior management of institution do not bear the full consequences, or are deliberately ignorant of, their actions, and therefore have a tendency to act less responsibly than they otherwise would, leaving another party (taxpayers) to bear responsibility for the consequences of those malevolent actions. In simplest terms, for example, an individual with insurance against automobile theft may be less vigilant about locking his car, because the negative consequences of automobile theft are (partially) borne by the insurance company.

In foreign policy terms, consider the case of hostage-taking. If the U.S. were to act humanely and try to come to the aid of hostages of terrorists, it would encourage terrorists to think that hostage-taking was a productive enterprise, thereby possibly encouraging more hostage-taking and harm to U.S. citizens. Based on past experience, the U.S. Government concluded that making concessions or negotiating with hostage takers in exchange for the release of hostages increased the danger that others will be taken hostage. Consequently, U.S. Government policy is to deny hostage takers the benefits of ransom, prisoner releases, policy changes, or other concessions. The U.S. government has in effect minimized the moral hazard of hostage-taking.

Moral hazard is also related to information asymmetry, a situation in which one party in a transaction has more information than another. The party that is insulated from risk generally has more information about its actions and intentions than the party paying for the negative consequences of the risk. More broadly, moral hazard occurs when the party with more information about its actions or intentions has a tendency or incentive to behave inappropriately from the perspective of the party with less information. as in trader / stockbroker – client relationships.

Face it: you’re being took. It’s simply not an equitable relationship, based on a “win-win” model. And that’s why sometimes increased government regulation of the negative impacts of unbridled free-markets become necessary.

Read more about “The Need for Failure” here.