“Because that’s where the money is” –

Willie Sutton, when asked why he robbed banks

——————————————————–

The New York Times ran a story this past Sunday noting that some U.S. universities that set up operations in Dubai are having trouble attracting enough students. Apparently, the economic downturn there has hit Michigan State and the Rochester Institute of Technology especially hard. This might be a good moment to ask why so many U.S. universities create branch campuses in the Gulf in the past few years, and if this model is the best way for U.S. higher education to engage the world.

Michigan State Dubai: Looking to Fill Those Seats – Photo Credit: Michigan State University

The Times article notes:

In the last five years, many American universities have rushed to open branches in the Persian Gulf, attracted by the combination of oil wealth and the area’s strong desire for help in creating a higher-education infrastructure. Education City in Qatar has brought in Carnegie Mellon, Cornell, Georgetown, Northwestern, Texas A&M and Virginia Commonwealth.

It is worth noting that the “area’s strong desire” has been supported by large transfers of cash to American universities. “In Qatar in 1995, the country’s ruler, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, set up the Qatar Foundation, a multibillion-dollar endowment to fully finance universities that agree to open branches in a complex called Education City. The government pays full tuition for all Qatari students, who make up about half of the enrollment. Universities have complete control over their annually submitted budget, while all of their costs, including construction and salaries, are shouldered by the foundation. Weill Cornell Medical College, for example, has been promised $750-million over 11 years by the Qatar Foundation.” (From The Chronicle, 28 March 2008, Volume 54, Issue 29, Page A26). New York University received $50 million up front before it committed to building a campus in Abu Dhabi.

Not surprisingly, these pools of money attracted serious attention and a large collection of U.S., French, British and Australian universities flocked to the Gulf. Is it good for the development of higher education in this part of the Arab world? Although Harvard, Cornell, Georgetown, the Sorbonne and the London School of Economics offer a great deal of brand name prestige to the region, a RAND study last year made some more practical recommendations (for Qatar): start a community college, develop a liberal arts focus, begin an honors program at Qatar University (as opposed to importing one), and add master’s programs in career-related fields at Qatar University. This focus on local institutions makes great sense.

The Chronicle article from last year quotes Mourad Ezzine, a Middle East specialist for the World Bank who oversaw its recent report on education in the Arab world:

These US outpost campuses in the Gulf make me think of the phenomenon of “American” universities in many parts of the globe. Indeed, a couple of old and very successful examples exist, particularly the American Universities in Beirut and Cairo. But more recent examples have had a difficult time, including those in Kuwait and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Others, like Al Akhawayn University in Morocco, are American in style but have no formal chartering in the U.S. (as AUB and AUC do). The U.S. Government should carefully consider other options before it supports the establishment of another university with its name on it. To truly support the establishment of a serious university starting from scratch takes hundreds of millions of dollars and decades of patience; this is not a strong suit of government programming. The American University of Bulgaria has required much more money from USAID than ever anticipated. It is successful by some measures, to be sure, but at what cost?

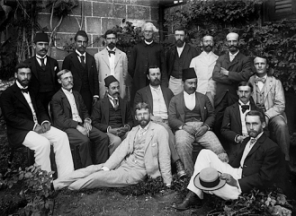

New York State granted a charter to Syrian Protestant College in 1863. Pictured here is the first graduating class. Photo credit: AUB

In many cases it makes much more sense to work closely with already-existing universities to enhance their capacity to educate that country’s citizens. For example, why establish an American University of Palestine (as has been proposed) instead of working to support Birzeit University? The latter has the history, credibility and connection to its population. It’s not to say that an American university (in whatever form) would never make sense, just that strengthening existing universities usually is less expensive, more sustainable and more likely to educate a broader cross-section of the population.

The other part of the quandary in the Gulf relates to the U.S. universities themselves; what do they get out of this type of international engagement? A great deal of money, as was noted above. I do not begrudge universities seeking to generate funds to support their educational mission; higher education is a competitive market and, as with any large institution, money is required to implement even the noblest of programs. But money cannot be the only reason to open an overseas campus. If so, it would be much easier to, say, start professional sports programs on U.S. campuses. (Oh wait, someone already thought of that!)

Internationalization efforts can be implemented in a way that makes long-term sense for all involved. The programs that are best at creating international connections across a university (undergrad and graduate students, faculty, staff, even alumni) are those that integrate meaningful contacts and relationships. This should include students moving back and forth from one campus to another, faculty engaged in long-term research partnerships, administrators developing curricula as partners, etc. Dual diploma undergraduate programs that allow students to spend two years at their home campus plus two at a partner institution are a wonderful example of internationalization of higher education. Students study, live and eat together – they become lifelong friends and colleagues. Faculty and administrators also work very closely together on such programs. (My colleagues at the State University of New York won the Heiskell Award for International Exchange Partnerships in 2006-2007 for SUNY’s dual diploma program with Turkey.) True partnerships between U.S. and host country universities come in many forms in addition to the dual diploma model and there is a role that the U.S. Government plays in encouraging them. One model that works – but could use more support – is administered by Higher Education for Development.HED’s programs use funding from USAID and sometimes the State Department to foster university partnerships focused on a particular development issue (say, agriculture, community colleges or parliamentary internships). Ideally, the partnerships will expand beyond the one development focus and sustain itself when the grant funding runs out. Connections that are made in such programs are the very essence of what we aspire to when we speak about “globalization.”

What is taking place in the Gulf is another piece of the definition of globalization: the transfer of vast sums of money, the selling of corporate brand names (university brands, in this case) and the importation of institutional models that have little connection to their new owners. How do these outposts help to truly internationalize the home campuses of these U.S. schools? Perhaps in ways much like dual diploma programs. It is up to serious academic leaders and boards of trustees to ensure that happens and that this is not just a money grab. NYU’s plans appear to set the standard for how this model might work best, with recruitment plans that reach beyond the Gulf, a financial aid model that makes it affordable (the annual cost of attendance is a whopping $63,000), plans to truly integrate the Abu Dhabi and Manhattan curricula, and sustained engagement by NYU’s leadership (President John Sexton goes to Abu Dhabi every two weeks). Still, I’d be a little more convinced of the true academic mission of these international outposts if they weren’t all clustered around the wealthy Gulf states. How about just a few in Zambia or Guinea-Bissau?

Artist rendering of NYU Abu Dhabi: Virtual University? Photo credit – LA Times