The U.S. soccer team was lucky to tie its first game in the World Cup against a reputedly stronger team, but some Americans appeared unclear as to whom exactly they were playing. Many in the U.S. media, including The New York Times, the New York Post, Los Angeles’ Daily News and Fox News’s Greta van Susteren, referred to America’s opponent as “the British team.” Headline writers often settled for British, Brits, or Brit, and The Times-Picayune started an editorial “When the U.S. soccer team takes on Britain today…”

The team, of course, was not that of Britain, but England, which is only one of the nations that constitute Britain, otherwise known as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and which includes Scotland and Wales. It is confusing for foreigners that Britain, which includes Northern Ireland, is actually bigger than Great Britain, which doesn’t include Northern Ireland. Some other countries, such as France, add to the confusion by often calling the whole lot “England” (l’Angleterre).

Does it matter very much to anyone else? Well, it certainly does to England’s fellow Brits, the Scots and Welsh, who have their own national teams (as does Northern Ireland), and for reasons of historic and cultural rivalry often support England’s opponents. In the current World Cup there is even a mildly controversial group in Britain called A.B.E. (Anyone But England), composed largely of Welsh and Scottish fans pledged to back any other team against the English. None of the other British teams qualified for the finals in South Africa this year.

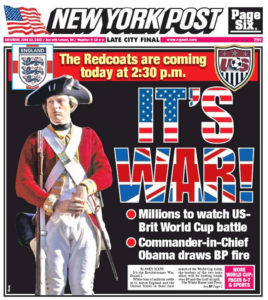

Much of the U.S. media used “British” and “English” interchangeably, and the contest against such a longstanding friend and enemy gave rise to numerous if somewhat strained allusions to the War of Independence, the Boston Tea Party, etc., and, more topically, the BP oil spill in the Gulf, as a result of which the New York Post, in an overheated headline, described the game as a “Toxic” Grudge Match. (Footnote: Although U.S. politicians have taken delight in slamming “British Petroleum” for the Gulf spill, BP has not been called British Petroleum for 12 years now.)

American comparisons of the U.S.-England match to the Revolutionary War were also somewhat off the mark. In the 1770s, the English were notably reluctant to fight against the rebellious colonists, being disinclined to take up arms against “fellow English Protestants,” leaving King George III to fill his ranks with Scottish and Irish soldiers (not to mention Germans) who felt no such compunction.

It was also slightly ironic to read accounts of Americans leaving no doubts as to where their patriotic feelings lay by decking themselves in red, white and blue, which are also the colors of the British flag, the Union Jack. The Stars and Stripes evolved directly from the red ensign of the British Royal Navy, containing the Union Jack in its top left corner, which was flown in the American colonies. In fact, of course, true England fans don’t display the Union Jack, but the St. George’s Cross flag of England, a simple red cross on a white field. This distinction was lost on The Sun out of Baltimore, which referred to “the white and red jersey of the Brits.”

Most Britons in the United States have long given up trying to explain these subtleties to Americans, who find them just about as easy to understand as the rules of cricket (incidentally, much simpler than those of baseball). But at least the Associated Press distributed a heart-warming story pointing out that U.S. soccer would not have come as far as it has without the help provided by English clubs and trainers.

So why, then, does Britain field four national teams while all other countries are limited to one each? It’s because the British invented international soccer, and had already organized a championship tournament between England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland in the 19th century. FIFA, the governing body responsible for the World Cup, accepted that the UK’s four national soccer associations had established their independence when it arrived on the scene in 1904.