Given the latest news of the strategic suicide bombing in Lahore, it’s important that we think hard about what we are fighting for in Pakistan. We need to ask: What is the U.S. fighting for in Pakistan? What is Pakistan fighting for? An answer to either question is not readily available. Perhaps neither question is well-phrased. But something like these questions must be asked from time to time.

The recent International Herald Tribune Op-ed piece published in the Times argues for a something like an answer to the two question. The answer: Democracy. Rather, we are all in the fight together to help expand the scope of democracy and its promotion in Pakistan. Jeffrey Gedmin and Abubakar Siddique, of the RFE/RL argue that now that the average Pakistani is tired of the corruption and discord in Pakistan, the U.S. government must step in and support Pakistani democracy. To be precise, along with supporting military’s return to the barracks, the U.S must support development and the promotion of democratic culture in FATA region whilst supporting a different priority– developing representative government in Islamabad by developing greater and more feasible democratic consensus. However, the one point of impact that cleaves the two arguments is that it is not impossible to think that supporting one could come at the cost of destroying the other.

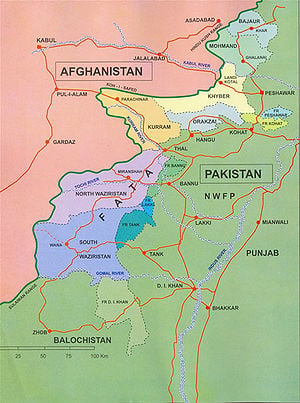

The Federally Administered Tribal Area ( FATA) of Pakistan, for far too long, has been isolated from the sphere of central government authority in Pakistan. It is run by governors who are appointed by the president, who only has the authority to implement the rules divined in FATA.The jurisdiction of the supreme court does not reach FATA, nor does the reach of the executive agencies that maintains the bureaucratic life of the country. It is represented in both houses of the Pakistani legistature, but it is not obvious whether the legislators from Karachi, Punjab belong to the same ‘tribe’ as those who show up in Islamabad from FATA to do their elected duty. Politics is, finally, a tribal affair. It is hard to see how developing greater transparency and democratic decision-making in FATA will translate to greater bonhomie in the two House of Parliament in Islamabad.

FATA is possibly the most dangerous place on earth for anyone with interests aligned with the U.S. government. It borders Afghanistan and supplies goods and services to the mainly ethnically Pashtun Taliban fighting the regime in Kabul, while providing safe havens for the Tehrik e Taliban (the loose association that we call the Pakistani Taloban) who have their sights set on Islamabad. Indeed the Taliban run Waziristan in all but name.

It is altogether unclear how democratic development in FATA will wind up strengthening representative democracy in Islamabad. That is to say, that though it might be somewhat clear what political development in FATA might mean–think greater tribal security and transparency in decision-making, a procedure that is then consolidated as a equilibrium decison-mechanism, that chimera, democratic culture–it is rather difficult to think how we might achieve transparency in candidate selection and how that might translate to a correlation between what ‘the people’ need or want in their politics and what the candidate can offer to satisfy those needs, wants. What does it mean when one speaks of ‘the people’ in FATA? What will solving these near intractable political problems achieve when the locus of development attention moves to Islamabad. Suppose that the people of FATA become democrats and develop a virtuous democratic culture and understand what they want and choose a representative who genuinely wants what the people want–what then? How does that help politics in Islamabad?

Political development in representative democracy means something like managing coalition building in a cyclical manner so that losers today can bet that one day soon they will be winners. It is hard to imagine even the most disinterested enlightened representatives from FATA holding that proposition, difficult that is without assuming into the equation, overt sources of private and personal corruption. Furthermore, it is nearly impossible to think that the interests of the typical Lahori are those avowed by the average Waziristani. What hope do we have then of political compromises that over iterated interactions between legislators actually constitute and comprise the meat of representative government?

Now none of this is to say that the U.S government or, indeed, the Pakistani government should not get busy trying to bring establish a development program in FATA with the goal to one day extend its writ into that region. (This will have been the true and ultimate measure of successful political development in Pakistan. As such this possible outcome is generations away.) But, I do wish to hold the point that democratic development in FATA does not imply political development in Islamabad. That is a different beast altogether and no calculation should think one immediately endogenous to the other–at least not yet.

FATA should be developed with domestic and international government and private aid. There are humanitarian grounds for that kind of government intervention into that region. There are liberal and pragmatic grounds for that intervention. As Ambassador Holbrooke claimed that a combat strategy in Kandahar requires that the average Kandahari have daily long, uninterrupted, electricity consumption, so democratic development in FATA requires that each child be educated to national standards without having to seek recourse to the Taliban for his basket of goods and groceries.

Indeed it is possible that democratic development in FATA is necessary for political development in Islamabad–though I suspect this is too strong a case. Nevertheless it is not sufficient for that much vaunted and desirable goal.