As argued in an earlier post, President Obama’s state visit to India next month will be overshadowed by two inter-connected events: 1.) The ongoing erosion of his political authority at home; and 2.) continued setbacks in the U.S. effort in Afghanistan.

As argued in an earlier post, President Obama’s state visit to India next month will be overshadowed by two inter-connected events: 1.) The ongoing erosion of his political authority at home; and 2.) continued setbacks in the U.S. effort in Afghanistan.

With the Obama administration’s formal review of Afghanistan policy set to begin in December, influential voices are starting to call for a fundamental change of course from the strategy that Mr. Obama laid out at the end of last year. Two new reports – by the informal Afghanistan Study Group and the prestigious International Institute of Strategic Studies in London – propose drastic reductions in the Western military presence in that country (read here and here). Robert W. Blackwill, U.S. ambassador to India and deputy national security advisor under President George W. Bush, has issued a similar call (read here and here), recommending a de facto partition of Afghanistan that cedes control to the Taliban of the Pashtun heartland in the country’s south and east while limiting U.S. involvement to the northern and western regions. (On the continuing loss of elite support for the conflict, read here.) Add to this mix a recent CNN poll that founds 58 percent of Americans now opposed to the war, with dissatisfaction especially strong among Democrats, and the pressure will be on Mr. Obama to make good on his promised drawdown of U.S. military forces in mid-2011.

Sounding an unusual cautionary note, however, is Robert D. Kaplan, a journalist whose work has a wide readership in U.S. elite circles. Writing in a new report – which is based on his forthcoming book, Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power – he argues that:

the deleterious effect on U.S.-India bilateral relations of giving up on Afghanistan should be part of our national debate on the war effort there, for at the moment it is not. The fact is that our ability to influence China will depend greatly on our ability to work with India, and that, in turn, will depend greatly on how we perform in Afghanistan.

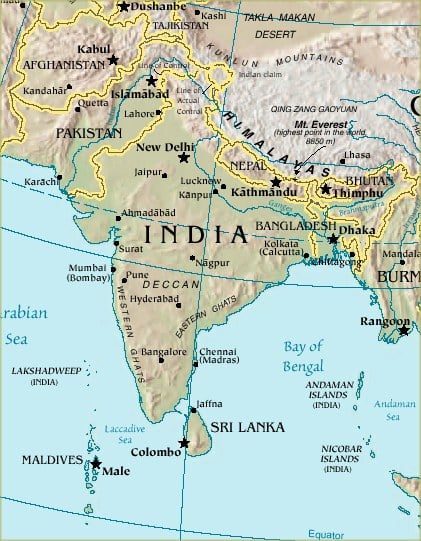

Kaplan warns that due to history and geography, security managers in New Delhi view Afghanistan not as a detached part of Central Asia but an organic element of the Indian subcontinent. Until the British colonial presence, the subcontinent’s invaders came from its northwestern frontier. Moreover, the region that encompasses northern India along with Pakistan and much of Afghanistan has traditionally been governed by a single imperial authority. Thus, Kaplan argues, it “is not only natural but historically justified” for New Delhi to care profoundly about who rules Afghanistan.

Kaplan warns that the outcome of the upcoming U.S. policy review is fraught with momentous geopolitical implications:

The quickest way to undermine U.S.-India relations is for the United States to withdraw precipitously from Afghanistan. In the process of leaving behind an anarchic and radicalized society, which in and of itself is contrary to India’s interests, such a withdrawal would signal to Indian policy elites that the United States is surely a declining power on which they cannot depend…. [A]n American failure in Afghanistan bodes ill for our bilateral relationship with New Delhi. Put simply, if the United States deserts Afghanistan, it deserts India.

(Henry A. Kissinger has made a similar point, writing this summer in the Washington Post that a precipitate withdrawal “would be seen in India as an abdication of the U.S. role in stabilizing the Middle East and South Asia and spur radical drift in Pakistan. It would, almost everywhere, raise questions about America’s ability to define or execute its proclaimed goals.”)

In the event of an U.S. failure in Afghanistan, Kaplan warns, New Delhi might be tempted to make common cause with Beijing regarding security arrangements in Central Asia. But even if New Delhi resists tilting toward its northern neighbor, the loss of India as America’s strategic partner will itself have a sharp effect on the U.S.-China balance of power.

U.S. officials have put out word that the end-of-year strategy review is more about fine-tuning than launching a major shift in direction. And in a letter to Congressional leaders yesterday, Mr. Obama declared that “we are continuing to implement the policy as described in December and do not believe further adjustments are required at this time.” But these words will be of little comfort to New Delhi given the unflattering portrait in Bob Woodward’s new book, Obama’s Wars. Here Obama emerges as the most reluctant of warriors, one driven by domestic political compulsions and fixated on finding an expeditious way out of Afghanistan. (Read the book’s excerpts in the Washington Post here.)

Regardless of the immediate outcome of December’s review process, governments in South Asia are behaving as if a visibly reduced U.S. involvement in Afghanistan in the coming year is a foregone conclusion. This perception, which will only be reinforced if the Democratic Party suffers major setbacks next month, will color not only how New Delhi approaches Mr. Obama’s state visit but how it weighs the prospects for U.S.-India relations.