Cartel-on-cartel violence may offer Felipe Calderon and Barack Obama the political solution they seek in Mexico, and give international stakeholders in the Mexican drug industry the break they need to get back to ‘business as usual’–generating billions in drug dollars, cash that, as it ‘gets cleaner,’ is transformed into capital by ‘legitimate’ investors who create billions more.

Cartel-on-cartel violence may offer Felipe Calderon and Barack Obama the political solution they seek in Mexico, and give international stakeholders in the Mexican drug industry the break they need to get back to ‘business as usual’–generating billions in drug dollars, cash that, as it ‘gets cleaner,’ is transformed into capital by ‘legitimate’ investors who create billions more.

Drug barons are bottomline guys–they’re in it for the money (328bn)–and 28,000 dead with more violence to come isn’t good business.

So here’s the plan. An ad hoc crime group called ‘the New Federation’–an alliance of rival cartels brokered by the Gulf cartel with Guzman’s Sinaloa crime group, and the Michoacana Family–takes down Los Zetas, the violent breakaway hit squad once affiliated with the Gulf cartel, and the purveyors of the current mayhem in Mexico.

According to a report, by Austin-based “global intelligence” firm STRATFOR, “The cartel warfare crippling Mexico will continue until the Zetas, a powerful offshoot of the Gulf Cartel, are subdued by other drug gangs or Mexican authorities. . .”

Given that Mexican authorities appear unable to counter the spreading violence in Mexico–the assassinations of elected officials, kidnappings, car bombings, birthday party massacres, and the proclivity of gang members to hang decapitated bodies from highway overpasses–that road, so to speak, seems closed.

And since the United States is prohibited (by the Brownsville Agreement) from intervening in Mexico’s ‘sovereign affairs,’ reaching out to the ‘enemy of our enemy,’ while not a guaranteed strategy is, at least, a familiar one.

“Fearing the might of Los Zetas, the Gulf Cartel reached out to their longtime enemies, the Sinaloa Federation, and asked for their assistance in dealing with Los Zetas” wrote Scott Stewart, a STRATFOR analyst.

“The leader of the Sinaloa federation, Joaquin ‘El Chapo’ Guzman Loera, has no love for Los Zetas, who as the former military arm of the Gulf Cartel engaged in many brutal battles with Guzman’s forces. Together with another enemy of Los Zetas, La Familia Michoacana, Guzman joined forces with the Gulf Cartel to form an organization known as the New Federation.”

From Bad to Worse

Not everything about this plan is rosy, of course. First, things may get worse before they get better.

Less competition between warring cartels would reduce the violence, Stewart said. But during the short term, the aggressive move by the New Federation will likely increase the bloodshed.

And then, of course, there’s the old proverb about the fellow so focused on keeping the tiger away from the front door that he misses the wolves sneaking in the back.

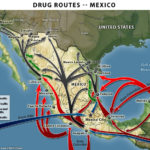

The New Federation aims to destroy the Zetas and the Vicente Carrillo Fuentes Organization (also known as the Juarez Cartel). If the New Federation succeeds, and manages to marginalize the Arellano Felix Organization (also known as the Tijuana Cartel), it could dominate Mexican drug smuggling routes into the United States.

What will the New Federation want, after it neutralizes Los Zetas, as payback?

A deal.

The kind of deal, in fact, that drug lords have managed to negotiate in Colombia, whereby big-time traffickers transform themselves, with the acquiescence of the government, into politicians, then elected officials–first at relatively low and local levels, and later, into the higher ranks of political power.

It’s not a far road to travel.

Right now, close to 8 percent of Mexico’s municipalities are under control of narco-cartels, and almost 73 percent are under some degree of cartel influence.

The Colombianization of Mexico

A Podor 360 report by Jorge Garay and Eduardo Salcedo-Albaran (Fundacion Metoda, Colombia) speaks clearly to the “Colombianization” of drug-trafficking in Mexico:

. . . after 30 years of battling the state, Colombian drug-traffickers have learned that infiltrating, co-opting and using the state is more beneficial than fighting it. This last development marks the most sophisticated and complex phase for Colombian drug-trafficking-one that the nation is still going through.

The Mexican cartels will very soon learn that confrontation with the state can’t last forever, and that the best thing to do is strike a deal. The more “legal” those agreements look, the more useful they will be to them.

La Tuta, the leader of the Michoacana Family (one of Mexico’s most feared organized crime groups), said as much in July 2009 when he phoned a television program to pay his respects to President Felipe Calderón and to express his interest in seeking an agreement to end the war.

La Tuta didn’t ask for an agreement because his cartel was weak, but rather because he seemed to anticipate that in the long run agreements would prove less costly than waging war.

Under-the-table agreements between drug-traffickers and local government in Mexico have a long history. Experts say it is thanks to those unwritten pacts that the country avoided the violence being witnessed today. But changes to the political structure resulted in those accords being broken and the present chaos in which rival cartels compete for control over drug distribution routes to the U.S. and Europe.

At first glance it appears as if Mexico has arrived at a point of no return. The declaration of war (by Calderon) on drug-trafficking has made it impossible to return to the old deals. That is why Mexican drug-traffickers, after being openly confrontational, may now seek lower level deals, likely financing municipal electoral campaigns and promoting social and political movements.

By co-opting the political class, drug-traffickers can get the law on their side, which is every drug-trafficker’s most desired goal. It’s possible that something like this took place during Mexico’s last elections.

In September, Julio Cesar Godoy, was sworn in as a federal congressman for Mexico’s leftist Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) despite facing 2009 drug-trafficking charges for alleged ties to La Familia–an arrest warrant for Godoy existed before his election. As a member of Congress Godoy has immunity from prosecution.

The Podor 360 article by Garay continues:

It is how powerful players compromise in ways they want to believe (and want us to believe) are short-term and the best they can do.

There are other, better, and certainly braver ways the United States could change the course of history in Mexico, but making or justifying more controversial choices might also change the course of too many political careers and trigger what Washington would undoubtedly view as unwarranted political upheaval.

This is a high-risk proposition, not for law-abiding citizens on either side of the US-Mexico border, but for the governments and leaders that control their destinies, and there are no guarantees.