WikiLeaks: the New Napster

Leaks from Unlikely Sources

Welcome to 21st Century Diplomacy, State Department.

WikiLeaks’ massive cache of over a quarter million sensitive State Department cables is a bleak reminder that everything in in our Brave New World is ones and zeros- and ones and zeros are easily copied.

Back when Daniel Ellsberg stole the Pentagon Papers, he had to spend long, dangerous nights photocopying sensitive information, then smuggle it out to the major papers, who printed it as a physical book. The process took ages.

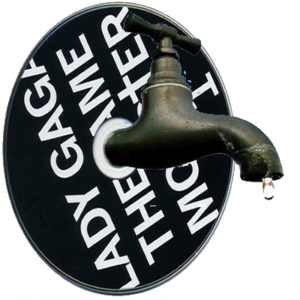

When Bradley Manning allegedly vacuumed up all this information from his secured network, he just had to get it out on a Lady Gaga CD and send it off to WikiLeaks’ servers.

It’s the Napster effect, and is hitting with as much as a disruptive crunch as that music sharing site did. The RIAA, one of those groups everyone loves to hate, went ballistic, filing barrages of lawsuits to try and stop the collapse of their entire business model in this new reality. Napster’s long gone, successfully killed by the action of those corporations, but other file sharing systems – more distributed, harder to kill – persist.

The stakes are higher with WikiLeaks. The most powerful government in the world is threatened by a new reality undermines the fundamental business model of diplomacy – privacy. Diplomats need to be able to negotiate agreements shielded from hysterical political rhetoric; their political leaders are the ones who need to handle communications with the public. Similarly, you can’t get the frank opinions of foreign businessmen, sheiks or politicos if they believe their words will condemn them from the pages of the New York Times. More so than most government fields, international diplomacy must be shielded from the whims of an ill-informed public.

Hence the enraged and erratic response of the US government to the leaks and their publication, despite the fact that the cables have – so far – largely revealed the professionalism and wordsmithing skills of America’s diplomats.

It’s not fair to say that after WikiLeaks the genie is out of the bottle; this particular genie packed her bags, set a forwarding address, and jumped on a plane years ago. It lays bare the difficulty any large organization will have in keeping its secrets. You can try and epoxy the USB ports on computers and ban carrying camera phones into secure locations, but a motivated, trusted person is going to be able to get information – and get it out. Then it’s gone.

WikiLeaks is quite new in providing a different set of motivations for the theft of secrets. The same risk has always existed for stealing on the behalf of foreign governments, but now those trying to undermine US policy by public exposure have a way to get information into the hands of the world.

It’s too bad, for a number of reasons; a lack of internal information sharing prevented “connecting the dots” for the 9/11 attacks. This will inevitably lead to further clampdowns and secrecy. The pirate’s maxim – “two people can keep a secret if one of them is dead” – will now be too much in mind of government data security experts.