These are troubling times for Lebanon. Even for a country under the thumb of Damascus, things seem to be out of their control. The most anyone can do is just wait and see.

Since 1963, Syria has been under control of the Baath party. Hafez Assad took power in 1970 and ruled the country with an iron fist until he died in 2000. His son, Major Basil Assad, had been groomed to take his place, but the young man died in a car accident in 1994 at the age of 31. The regime was forced to go with Plan B.

“Plan B” was Basil’s younger brother, Dr. Bashar Assad. Bashar was studying ophthalmology in London when his brother died and he was forced to return to Damascus and enlist in the army. Bashar Assad was never supposed to be “the guy”. Bashar took power upon his father’s death, insulated by a wall of mostly Alawite men chosen by Assad Sr. to facilitate his son’s ascension.

The Alawites are considered to an offshoot of Shia Islam. In the early part of Hafez Assad’s reign, he was met with challenges from Syria’s Sunni majority, who believe the Alawites to be infidels. In 1973, Lebanon’s most prominent Shiite leader issued a fatwa declaring Alawites to be a full part of the Shiite family. In return, Sadr received support in developing his Amal militia, a precursor to Hizballah. (Assad also threw his support behind Sadr’s friends in Iran when they overthrew the Shah in 1979.)

After those shaky few early years, the next internal challenge Assad faced was the revolt of the Muslim Brotherhood in the early 1980’s. The unrest came to a head in 1982, when Assad’s forces surrounded the Muslim Brotherhood stronghold of Hama. The army razed the town killing thousands in the process. For the rest of Assad’s reign, he would not face another serious challenge from within.

As the protests in Syria continue to spiral, the memory of Hama is in the minds of the protesters. When Bashar Assad took power in 2000, he was considered to be a “reformer”, a characterization still maintained by the West, including US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. It was unclear whether Bashar was capable of playing by what Thomas Friedman famously termed “Hama Rules” in his book From Beirut to Jerusalem.

With the unrest growing and spreading to the capital, it seems we are learning the answer. The city where the protest began, Deraa (sounding eerily similar to “Hama”) is currently under siege. Deraa is surrounded by the military. Water, electricity, and food supplies have been cut.

But there is a difference between a siege of a town and its complete destruction. If Bashar Assad gives the order to shell Deraa into oblivion, we will know that he is capable of playing by Hama Rules.

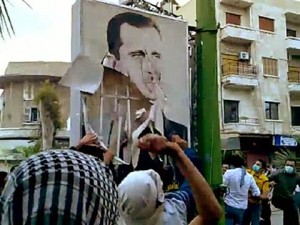

The protest that started in Deraa have spread to the rest of the country. Thousands of people are in the Damascus calling for the removal of the regime, a scenario that was previously unthinkable.

The protest that started in Deraa have spread to the rest of the country. Thousands of people are in the Damascus calling for the removal of the regime, a scenario that was previously unthinkable.

To date, over 450 people have been killed. The cycle is a familiar one, repeated many times throughout the Great Arab Intifada: people protest, the government cracks down, people are killed, protest grow following funeral and Friday prayers, repeat.

The implications of the unrest in Syria for the region and beyond are many. Starting with Lebanon, refugees from Syria have already started pouring over the border to escape the violence. Sunni Lebanese politicians have been accused of encouraging the protests and even funding the opposition. Syria holds tremendous influence in Lebanon and what is felt in Damascus will surely be felt in Beirut.

Lebanon was already in a tenuous political position when the protests started. Hizballah had just supplanted Saad Hariri as Prime Minister with their own man, Nijab Mikati. As a result, Mikati is still in the process of forming his new cabinet of ministers and Lebanon is forced to weather the current crisis without a government.

The situation seems to be a tinder box. It’s alarming to think about the prospect of the United Nations Hariri Tribunal releasing handing down its indictments right now. Even without that, it’s conceivable that Assad could unleash one of his many proxies in Lebanon to start trouble as a distraction or misdirection.

That scenario is unlikely however, because the only distraction big enough to avert the world’s eyes from another Hama-style massacre would be for Hizballah to start hurling rockets at Israel. In the wake of the damage done in the 2006 War combined with all the political gains Hizballah has made since then, the group would likely balk at the idea of starting another fight with Israel at this point.

That scenario is unlikely however, because the only distraction big enough to avert the world’s eyes from another Hama-style massacre would be for Hizballah to start hurling rockets at Israel. In the wake of the damage done in the 2006 War combined with all the political gains Hizballah has made since then, the group would likely balk at the idea of starting another fight with Israel at this point.

The West, led by the United States, has tried to enact sanctions against Syria in the UN Security Council, but faced resistance from China and Russia, as well as Lebanon, who is currently serving as a non-permanent member. Russia and China have their internal concerns and are understandably weary about encouraging international interference in what they see as the domestic affairs of the state.

The unrest in Syria has many implications for the Middle East and beyond. For the Lebanese, the result is a new sense of powerlessness over their destiny. Its one thing for a state to have its own problems, but what do you do when your overlord is convulsing?

The billion dollar question right now is what will happen if the Assad regime falls? This is a strategic question for the West, but the outcome will have vast consequences for Lebanon. Suppose a Sunni regime ascends to power; will that translate to the Sunnis in Lebanon wielding more power? How will the other sects react to this scenario? Suppose the new regime is hostile or neutral towards Iran; what will the mean for Hizballah, whose weapons and cash from Iran are shipped through Syria? Will Hizballah then become isolated in Lebanon? How would they react to the isolation?

Iran is in a similar situation. If the Assad regime is replaced by one that is less sympathetic to their needs, and perhaps closer with other Sunni Arab countries like Egypt or Saudi Arabia, the Islamic Republic will face a whole new level of international isolation. In this perceived zero-sum game, any loss for Iran is seen as a gain by the West. The loss of such a crucial ally combined with a deteriorating internal situation could make Tehran more pliable to the demands of the by the United States.

Saudi Arabia though is in an odd position. On one hand Iran is their arch enemy, and the casting off of the Assad regime would surely be a significant blow to the Ayatollah. Some analysts have put forth the idea that thwarting Shiite Iran is the key national security issue of the Kingdom (see: Bahrain, Lebanon, and Yemen).

But on the other hand, the Saudi royal family does not wish to see another dictator removed from power in the Middle East, as it increases the chance that they could be next. Both Iran and the Arab Intifada pose existential threats to the regime in Riyadh, but it seems the Saudis have deemed the Intifada the more immediate threat.

Israel also has a great deal to be concerned with. Syria lost the Golan Heights territory to Israel in the 1967 War and the two have been in negotiation for its return ever since. Damascus under the Assads maintained a hostile-yet-predictable stance towards the Jewish State over the years and it seems that Tel Aviv is in no rush to see another regime, possibly under the leadership of the Muslim Brotherhood, take its place.

Were this to be the case, Israel could find itself boxed in by two countries under the influence of the Muslim Brotherhood. The last thing Israel wants to see is an emergent- and possibly hostile- Syria and Egypt united under political Islam, which could threaten Israel’s national security and weaken their hand significantly when trying to arrive at a final solution over Palestine.

Just last week, Hamas merged with the Palestinian Authority in a move that some analysts attributed the Hamas’s insecurity concerning the unrest in Syria. Hamas has enjoyed the patronage of Syria for years, and it’s leader-in-exile, Khaled Meshaal, lives in Damascus. Were Hamas to lose that support, the group could be dramatically weakened. The move to merge with the PA is understandable on the grounds that they risk losing relevance should the Assads be removed from power.

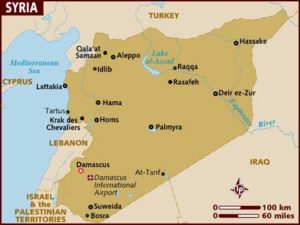

The United States is watching the unrest in Damascus closer than perhaps any of the other Arab revolts. The key to Syria’s power has always been geography: it borders Turkey, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, and Iraq. The Assads in particular have deftly exploited this position, gaining enough concessions to remain in power for forty-plus years.

As the United States deals with a myriad of foreign policy obstacles and issues in the region, Syria is always in the picture. The new Cold War with Iran; the safety and security of Israel; the Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; the emergence of Turkey; maintaining the balance of power between the Sunnis and the Shia…Syria is close to every single issue. The outcome of the unrest will have enormous consequences for the United States, especially if the Assad regime falls.

As the United States deals with a myriad of foreign policy obstacles and issues in the region, Syria is always in the picture. The new Cold War with Iran; the safety and security of Israel; the Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; the emergence of Turkey; maintaining the balance of power between the Sunnis and the Shia…Syria is close to every single issue. The outcome of the unrest will have enormous consequences for the United States, especially if the Assad regime falls.

Syria represents a growing concern for the region. The Assad regime has plugged Alawite loyalists into every meaningful post in the military, security, and intelligence apparatus. For revolutions to succeed swiftly, the protesters need the help of the military, or at least their neutrality. This was the case in Egypt and Tunisia. But in Libya and Bahrain, we have seen what happens when the will of the people is opposite that of the military.

If the regime can quell the unrest with violence, it does. If not, the country descends into chaos and civil war. Right now, it looks like the demonstrations in Syria will continue to grow, especially since the rate of protesters being murdered continues to increase. At the same time, the goal of the Syrian military is to protect the regime, and that is unlikely to change. Unfortunately, steadily increasing cycles of violence are likely in the near-to-medium term.

As a side note, it is interesting to consider the possibility of jihadis coming to fight the Assad regime if the country descends into civil war and the conflict is perceived by the region’s Salafi warriors as “a battle to protect good Sunni Muslims from the heretical Alawite murderers”. Damascus has fostered extremist groups in the region for so long, the irony of them coming home to roost is delicious to ponder.

For now, all eyes are on Syria to see what will happen next. The prospect of the downfall of the Assads has vast implications for the Lebanon and the Middle East. With the removal of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt and Zine el Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia, and the likely removal of Ali Abdullah Saleh in Yemen and Muammar Qaddafi in Libya, we could see the end of 125 years of despotic rulers in the Middle East. This has been a remarkable year for Arabs, and it’s only April.