The UN High-Level Meeting (HLM) on Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) was held last week in New York and resulted in the adoption of a Political Declaration (PDF here). As I feared a few weeks ago, the declaration is weak and does not set hard goals or targets to curb the NCD epidemic, which caused two-thirds of all deaths in 2008, 80% of which were in low- and middle-income countries. This HLM was widely anticipated, as it was the second time such a meeting has been called to discuss a health issue, but the disappointing results are not surprising, given contention prior to the meeting around the involvement (or undue influence) of the food, alcohol, and drug industries and the unwillingness of influential Member States, such as the US, to commit to defined goals. The two largest successes of the HLM appear to be that NCDs are now on the global health table for discussion and that the UN has recognized the crucial links between NCDs and development. These are laudable outcomes, but they are not enough.

The Declaration uses standard non-committal UN language–“profound concern,” “multisectoral approach,” and “advance the implementation” come to mind–and calls for voluntary targets to be set by 2012 and a progress report in 2014. Miriam E. Tucker of Family Practice News reports that revisions just prior to the HLM “essentially [stripped] the document of specific and time-bound targets.” These omissions included a goal to reduce preventable deaths from cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic respiratory disease by 25% by 2025 and a goal to reduce salt intake to less than five grams per day per person. In teh document, there are the beginnings of ideas that could one day lead to stronger commitments on NCD prevention and treatment, such as calling for governments to approach population-wide interventions that address NCD risk factors, integrate NCDs into health systems, and learning from infectious disease epidemics to improve responses, but the language is vague. Furthermore, the Declaration does raise some specifics about stemming tobacco use worldwide, but Big Tobacco is the go-to villainous whipping boy of NCD prevention (with absolute reason, of course). None of this is a shock coming from the body that did implement some responses to HIV/AIDS but only held a formal HLM on HIV/AIDS in 2001, a full twenty years after the beginning of the epidemic.

It is possible to have stronger responses to NCDs, which can be see at the local and national level. New York City has led the way, for example. As the UN itself reported in a press release, NYC Mayor Michael Bloomberg addressed the HLM on the final day and cited his and the previous administration’s efforts to prevent NCDs in the city. Smoking bans in restaurants, bars, parks, and beaches, a costly tax on cigarettes, and media campaigns have contributed to a drop in smokers’ numbers, from 22% of the city’s population in 2002 to 14% in 2011, with teenage smokers dropping from 18% to 7% over the same period. Bloomberg estimated that these municipal endeavors have saved 1,500 lives. In 2008, NYC became the first American city to require that restaurants post calorie charts. The city has also increased the number of “green” street carts (as opposed to the ubiquitous hot dog and pretzel vendors), banned or otherwise restricted trans fats, worked with manufacturers and grocers to reduce salt in food products, and initiated a public education campaign. According to Bloomberg, a New Yorker’s life expectancy has risen 1.5 years from 2001-2008, above the national average, and no additional city funds were spent on the smoking bans, trans fact restrictions, and calorie postings. Tobacco taxes went directly to the city’s coffers. Now, I’m realistic: we’re not going to see a trans fats ban or calorie counts in spaza shops, dibiteries, or bake and shark shacks any time soon. However, increased taxes on tobacco and alcohol that then fund public education campaigns are efforts that can start in a relatively short period of time, if the political will exists and the global community participates.

There are other medical solutions to NCD prevention and treatment that fall somewhat under the dubious “appropriate technology” category–except that they are as, if not more, effective as their higher-income counterparts. The New York Times reported this week on the success of a screening and treatment program for cervical cancer in Thailand. Cervical cancer used to be the number one cancer killer of women in the US, but changes in health care interventions and public awareness, such as frequent pap smears, have lowered its lethality. 250,000 women still die each year from cervical cancer, however, and many developing country health infrastructures are not equipped to screen and treat women. In Thailand, nurses brush vinegar on a woman’s cervix, and any pre-cancerous or cancerous lesions will appear white. These are frozen off with carbon dioxide, which can be procured from, as Times writes, the ever-present local Coca-Cola plant. While pap smears require a lab and biopsies most often require a doctor, a nurse can be trained to do both procedures. Freezing off the lesions (cryotherapy) is 90% effective with minimal common side-effects. One of the pioneers of this technique, Thai gynecologist Dr. Wachara Eamratsameekool, said: “Some doctors resist. They call it ‘poor care for poor people.’ This is a misunderstanding. It’s the most effective use of our resources.” Now, I’m completely for equal health care and treatment worldwide, and I do not like the “appropriate technology” argument, generally (see part 4 of my last post). This solution, however, is working and does not result in a lower efficacy. In fact, if I were given the choice between vinegar or a biopsy, I’d probably go with the vinegar (especially given skyrocketing health insurance costs in the US…for another day). More health solutions like these must be discovered, developed, and implemented. Equal access and treatment become more attainable when we can use efficient, on-hand resources that offer the same successes as more expensive, less available options.

The non-communicable disease epidemic is not going to go away, and as just about everyone says, it’s going to get a whole lot worse. The time to act is now–before we reach a crisis point that we cannot reverse. In those places where the food, alcohol, drug, and tobacco lobbies are keeping national governments from curbing NCDs, local governments and community leaders should step forward. New York City did just that. More medical and public health researchers should be looking for novel approaches to prevent, screen, and treat NCDs that take into account local conditions and needs without compromising on the quality of these interventions. Just as the HIV/AIDS epidemic required grassroots activism to force change, so does the NCD epidemic. It is time for individuals to act, since it is apparent that the UN and global leaders will not step up as needed now.

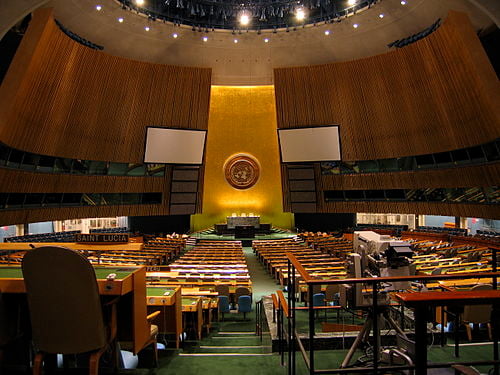

Header photo by Chris Erbach [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC-BY-SA-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons