The curious timing of the bounty on Hafiz Saeed raises the issue of whether U.S. policies toward New Delhi and Islamabad are in sync.

If anything, the $10 million bounty the Obama administration offered last week for information leading to the capture and arrest of Hafiz Muhammed Saeed, a high-profile jihadi leader in Pakistan, is long overdue. Still, the announcement’s particular timing is curious.

If anything, the $10 million bounty the Obama administration offered last week for information leading to the capture and arrest of Hafiz Muhammed Saeed, a high-profile jihadi leader in Pakistan, is long overdue. Still, the announcement’s particular timing is curious.

Saeed is a founder of the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT, or “Army of the Pious”), one of the world’s largest Islamist terrorist groups, which was originally formed to wreck havoc in India but has now developed global capabilities. He is widely considered to have masterminded the horrific November 2008 attacks in Mumbai that killed over 160 civilians, including six Americans. He has close personal ties with Osama bin Laden that stretch back to the 1980s and LeT has a long history of institutional links with al Qaeda.

The U.S. State Department justifies the bounty on the grounds that “this kind of reward might hasten the judicial process.” But why make the announcement now? After all, Washington has branded LeT as a foreign terrorist organization since December 2001. Following the Mumbai attacks, the United Nations designated LeT an al Qaeda-associated entity and placed Saeed on its targeted sanctions list. Responding to Indian requests for his extradition from Pakistan, Interpol issued a notice for Saeed’s arrest in August 2009. And in November 2010, the Obama administration itself put him on the U.S. sanctions list.

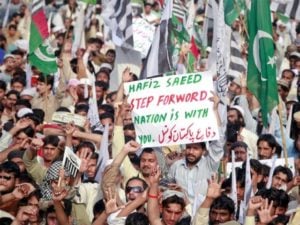

Unlike other terrorist kingpins who prefer a covert existence, Saeed has a penchant for the limelight. His vituperations against India and the United States are matched by a solid faith in his immunity from the Pakistani security apparatus. He resides openly near Lahore and recently has taken to traveling around the country speaking at large anti-American rallies organized by Difa-e-Pakistan (“Defense of Pakistan Council”), a coalition of some 40 militant outfits in which he is a prime mover. Following the bounty’s announcement, he held a press conference taunting the U.S. government: “Here I am in front of everyone, not hiding in a cave.” Underscoring his impunity, he spoke at a hotel across the street from the headquarters of the Pakistani army.

Adding to the puzzlement over the bounty decision is that it was announced in a way that further rubbed Islamabad’s already inflamed sensibilities, just when the Obama administration is attempting to mend fences with Pakistan. It was unveiled by Wendy Sherman, the U.S. Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, during her visit to New Delhi. The Obama administration no doubt wanted to address Indian complaints that it was letting Pakistan off the hook on the LeT issue. But from Islamabad’s perspective, the administration sent a quite different signal. As one observer notes the decision “marks a milestone in Washington’s growing impatience with Pakistan’s failure to act against terrorist groups that destabilize its neighbors and threaten the world” while also affirming “the U.S.-India relationship as the cornerstone of U.S. policy in South Asia.”

Moreover, the bounty offer was issued on the eve of Deputy Secretary of State Thomas R. Nides’ arrival in Islamabad. It was a strange way to commence a trip aimed at salvaging the collapsing U.S.-Pakistan relationship since it reminded his hosts of a series of embarrassing, even unpalatable, truths:

The reaction to the bounty from Nides’ interlocutors in Islamabad was predictable enough. Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani called it a “negative message” that would “further widen the trust deficit between the two countries.” Foreign Minister Hina Rabbani Khar stated that “Clearly it doesn’t bode well” for the debate now underway in the Pakistani parliament over the future course of relations with Washington.

Moreover, the bounty’s timing, which was approved by Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, had the potential of jeopardizing the mini-summit that Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari and Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh planned a few days hence. The meeting is another welcome sign of the detente process that has emerged over the past year between the two countries and Washington should have been doing all it can to support it rather than throwing in spanners.

The Obama administration is certainly correct that Saeed is a man who for too long has been allowed to escape the dispensation of justice. Yet the manner of the bounty’s announcement is open to question. As one analyst argues, “It seems a little odd to essentially highlight Washington’s inability to apprehend a suspected terrorist living in plain sight in a country that’s ostensibly a U.S. ally.” It also raises the issue of whether the administration’s policies toward New Delhi and Islamabad are in sync.

This commentary was originally posted on Chanakya’s Notebook. I invite you to follow me on Twitter.