In Part I of this blog I set the scene for the challenges ahead as societies continue to travel along the demographic highway. In this second installment I look at the novel solutions trying to add color to a greying democracy.

In a letter to the The Economist in January 2011, Reiko Aoki, Director of the Center for Intergenerational Studies at Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo, came up with an intriguing solution: give children a right to vote. In his proposal, Aoki argues for seriously considering giving children a vote… but: their parents would use it on their behalf (emphasis added). In this way, Japanese “parents with children under 18 would then control 37% of the vote.” It may be just the way it is explained, but to me however this seems less like giving children a vote than simply weighting the parents’ votes. Reading Aoki’s 2009 paper on the topic (available here), it becomes clear that this is what is intended: skewing the electoral system in the hope of boosting fertility rates.

The idea of giving children a vote can be traced to a paper written in 1986 by demographer Paul Demeny – leading to the coining of “Demeny voting” to describe the system. His aim was to promote pronatalist and family policies in order to try defuse the ‘demographic timebomb’ of aging. The point of the exercise therefore does not seem to actually politically empower those currently below the age of enfranchisement (the voting age being 18 in the majority of states, 20 in Japan, 21 in Singapore and 25 in Uzbekistan). It seems rather to pit generations against each other in the hope that those given a greater proportion of the votes through their children will automatically oppose policies designed to help their own parents. Politics would then present the ultimate moral dilemma; who do you love more, your parents or your children?

There are other possibilities than just simply changing the rules of the democratic game. The most obvious – though perhaps most challenging – would be to restructure the way the whole social welfare system is funded: away from the prevalent ‘pay-as-you-go’ system to a credible alternative. The complexities involved in implementing such a change would be immense, but not impossible – and possibly easier than the attempted demographic engineering taking place in certain states. Immigration presents another option. An increase in the working population would automatically lessen the burden on each member of that group. But what happens when these migrant workers retire?

Motivating those in the 18-30 age bracket to vote and become politically engaged seems the least ethically compromising solution. President Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign used social networking tools to successfully mobilize those sections of society not usually targeted by traditional election campaigns. Regardless of the greying of society, each citizen is supposed to be democratically equal – but research by David Nickerson argues that young citizens demonstrate low voter turnout precisely because they are ignored. It is widely assumed that because young people vote at low rates, efforts to boost their turnout will not be as cost-effective as campaigns targeting higher turnout age-groups. Issues affecting the youth demographic are therefore not central to campaigning, effectively alienating them from the political process – leading to low voter turnouts, and further sidelining. This vicious cycle needs to be broken – and though only gradually, in some countries steps are being made in the right direction.

Despite what cosmetic and pharmaceutical companies would like us to believe, aging cannot be prevented, and the slow inversion of the population pyramid looks set to test the democratic ideal of one person, one (equal) vote. Continuing to play the game but changing the rules to suit the players isn’t the way to deal with this situation. Societies need to think long and hard about the relationship between shifting demographics and politics. Perhaps this is the impetus needed for deliberative democracy to become a serious, viable choice.

—-

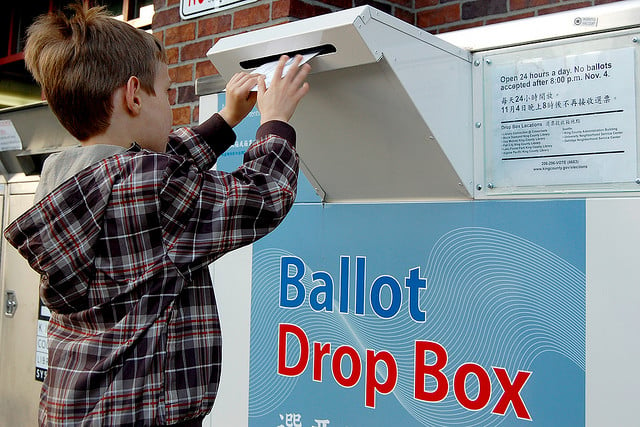

Image courtesy eagle.dawg/flickr, available here. Licensed via Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)