Last weekend, Hillary Clinton traveled to Norway for two days as part of her ongoing trip to Scandinavia, the Caucuses, and Turkey. In Norway, she first went to Oslo, where she had dinner with Norwegian Foreign Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre. He said to the Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten, “I’ve spoken with her many times, but we are both veterans of being places with limited time-tables….This was the first time we could sit, the two of us, and talk over dinner for several hours. That gave the meeting a new dimension, and we could take up issues and thoughts there normally isn’t time for.”

On Saturday, Hillary Clinton visited boarded the Helmer Hanssen research vessel in Tromsø to tour the nearby fjord. This is not the first time Secretary Clinton has visited the Arctic. While she was still a senator, she visited Svalbard as part of a congressional delegation to investigate climate change in August 2008. As Secretary of State, she attended the 7th Arctic Council ministerial meeting in Nuuk, Greenland in May 2011.

At the Fram Center in Tromsø, Secretary Clinton spoke to an audience with Store. In her remarks, she said, “Well, I think it is always important to have firsthand experience, if possible.” Secretary Clinton, who has visited a breathtaking number of countries, has indeed gained more firsthand experience of the Arctic than any other secretary of state in recent memory. She has also made a concerted attempt to get the Arctic, the Law of the Sea Treaty, and climate change on the agenda.

Clinton stated, “Now back in the United States, the Obama Administration is pushing hard to ratify the Law of the Sea Convention, which has provided the international framework for exploring these new opportunities in the Arctic. We abide by the international law that undergirds the convention, but we think the United States should be a member, because the convention sets down the rules of the road that protect freedom of navigation, provide maritime security, serve the interests of every nation that relies on sea lanes for commerce and trade, and also sets the framework for exploration for the natural resources that may be present in the Arctic.”

As I mentioned in a previous blog post, Senator John Kerry is helping to push along the ratification process by scheduling hearings. However, a final vote will not be taken until after the presidential election.

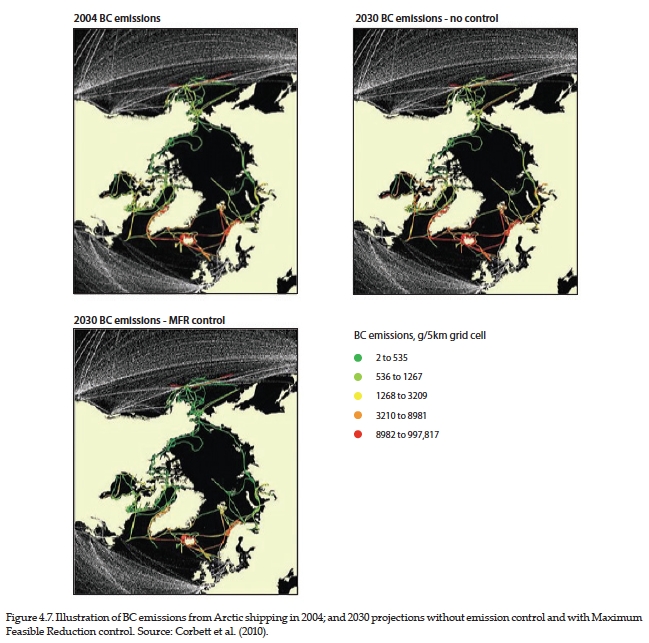

Clinton also spoke highly of the Climate and Clean Air Coalition, which was formed by six countries and the UN Environmental Programme this past February. The coalition is focused on reducing the amount of short-term climate forcings, namely methane, black carbon, and hydrofluorocarbons, in the atmosphere. This represents a shift in US policy, which previously focused on combating carbon dioxide emissions. However, targeting short-lived pollutants is arguably easier (and cheaper) than lowering carbon dioxide emissions. Black carbon, which is essentially soot, does not persist for a very long time in the atmosphere, and simple fixes such as replacing wood-burning stoves with gas-burning ones can help reduce the amount of pollutants in the air. Reducing the proliferation of black carbon is also important in the Arctic since it accelerates climate change in places that are cold and have lots of snow and ice. First, particles of soot floating in the atmosphere are especially efficient at absorbing sunlight, which therefore increases the surrounding atmosphere’s temperature. Second, the presence of something black on top of anything white causes it to melt more quickly due to the albedo effect. Some researchers believe that the proliferation of black carbon and ozone may explain why the Arctic is melting faster than models predict.

Already, Norway and several other countries have joined the coalition in the few months since its formation. Norway has actually donated $1 million to specifically target black carbon in the Arctic, and with good reason. As this report from the UNEP states on page 60, since the radiative forcing effect of black carbon on snow increases with latitude, “the Nordic countries are associated with the largest forcing per unit of BC emission due to emissions occurring at the highest latitudes.”

A map illustrating 2004 Arctic shipping emissions (top L) and two potential scenarios in 2030. From UNEP report, citing Corbett et al. (2010).

Some black carbon is produced by the transportation and oil and gas sectors. With the growth of the shipping industry in the circumpolar north, this could present a threat to the High North. Yet most black carbon in the Nordic countries and the U.S. is produced by routine fossil-fuel burning activities such as burning diesel fuel in an engine. In Canada and Russia, forest, grassland, and agricultural fires are the main source, so helping to control or even avoid unnecessary blazes such as the infamous Russian peat fires of 2010 could also be useful.

Clinton also spoke about international relations in the Arctic. One member of the audience asked her, “Madam Secretary, your colleague likes to talk about high north, low tension. There are lots of new countries that now have an interest in coming to the Arctic area. How do you see the potential for conflict in this area and the Arctic Council’s role in avoiding those conflicts?”

In her answer, Clinton stressed the primacy of the Arctic Council in addressing issues and potential conflicts in the Arctic. She responded, “Well, our goal is certainly to promote the peaceful cooperation that we think is called for in the Arctic. And the Arctic Council, which consists – at the core are the five Arctic nations, of which Norway and the United States are two, and then others with very direct interests, such as Iceland and Sweden, have been working without a lot of attention until relatively recently. And I think it’s a tribute to our foresight and our predecessors, and then certainly Jonas has been a global leader – not just a Norwegian leader – on bringing attention to the Arctic and, as he says, the high north, that we are operationalizing the cooperation that we have established through the Arctic Council.”

Clinton continued, “And you’re right that a lot of countries are looking at what will be the potential for exploration and extraction of natural resources, as well as new sea lanes, and are increasingly expressing an interest in the Arctic. And we want the Arctic Council to remain the premier institution that deals with Arctic questions. So one of the issues on our agenda is how we provide an opportunity for other nations very far [from] the Arctic to learn more about the Arctic, to be integrated into the cooperative framework that we are establishing, and in effect, to set some standards that we would like to see everyone follow.”

While she successfully avoided stating whether the U.S. would support a country like China gaining permanent observer status in the Arctic Council, it does seem like she is advocating for the involvement and integration of non-Arctic countries in the discussion. The U.S. and Nordic countries promote more multilateralism in the Arctic than more territorial, sovereignty-focused countries like Russia and Canada. However, given Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s recent overtures to China in the wake of President Obama’s rejection of Keystone XL, it wouldn’t be too surprising if Ottawa were to support China’s bid.

News Links

“Arctic warming means challenges, Clinton says,” Voice of America

“Climate change in the Arctic: Beating a retreat,” The Economist

“Sun shone on more friendly talks,” News in English (Norway)