Farnaz Fassihi is the Senior Middle East Correspondent for the The Wall Street Journal . Through her first account coverage of the region, her ability to look at events with an astutuly critical look, Farnaz has proved to be one of the leading authorities in Middle East politics. A graduate of English Literature from Tehran University and a Masters in journalism from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, Farnaz is the author of the internationally acclaimed book Waiting for An Ordinary Day: The Unraveling of Life in Iraq, which is a memoir of her four years of covering the Iraq war. Farnaz is the recipient of numerous prestigious awards in journalism, among them the The Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award and Overseas Press Club Award, both for international reporting of the 2009 Iranian presidential elections and the subsequent uprising. She is also recipient of the Henry Pringle Lecture Award for her Iraq coverage by Columbia University. Prior to joining the Journal, Farnaz was a roving foreign correspondent for the Star Ledger of Newark, N.J., and a reporter for the Providence Journal. Farnaz’s coverage of the Middle East and the international recognition that her work has won her have put her on the path to becoming one of the leading figures in American journalism.

What is your current role at the Wall Street Journal? How long have you been with the Journal?

I am the Senior Middle East Correspondent for the Journal based in Beirut, Lebanon. I cover Iran as well as the region, a mixture of news investigative and enterprise projects. I’ve been with the Journal since January 2003. Before Beirut, I was the Baghdad bureau chief from 2003-2006 covering the Iraq war and its aftermath.

Where were you born?

I was born in the United States. I grew up between two worlds and two cultures–in Tehran before the revolution and then in Portland, Oregon. I also lived in Iran for a few years during my college years because my family decided to return home.

Your family background goes back to the court of Naser el-Din Shah of Qajar, one of the longest ruling Persian monarchs. And your great great grandmother, Princess Taj al-Saltanah, was one of Iran’s leading women’s rights advocates. Can you tell us about your family background and the extent of influence Princess Taj al-Saltanah has had on you?

I think the most profound influence Taj al-Saltaneh’s life story had on me was growing up with a sense that a woman was no less than a man, even in Iranian society, and that I could achieve anything I set my mind to do. My bedtime stories, retold over and over by my paternal grandmother, were not about Cinderella but a real life princess who was also a strong-willed and independent woman. She broke taboos by becoming the first woman in court to shed the hijab and wear western clothes, bold enough to obtain a divorce and secretly attempted traveling to Europe even though her brother, then the King, had banned her from going. Taj al-Saltaneh later became a pioneer of women’s rights in Iran, leading a march to parliament to demand equal rights. She was also a real intellectual, an avid reader, writer, and painter who hosted a famous literary salon in her house for writers and musicians. I’d like to think that I’ve inherited some of those genes and her spirit.

Tell us about your education.

My education has primarily been in English, which explains why I’m more comfortable writing in English than Persian. I attended a British elementary school in Tehran and went to middle school and high school in the U.S. I received a bachelor degree in English in Tehran and a Masters Degree in Journalism from Columbia University in New York.

How did you end up in the journalism profession? Tell us about your journalistic journey to your current role at the Wall Street Journal.

My journey as a journalist has been a mixture of serendipity, ambition, and hard work. I stumbled into journalism by chance in my sophomore year at college when a reporter from The New York Times traveled to Iran and needed a translator. By the end of the first day, I knew this is what I wanted to do with my life because it combined my passion for writing with my curiosity for people and their stories.

I worked as a stringer for The New York Times and other foreign news outlets in Iran during my college years and then moved to New York to broaden my horizon and try and find a staff correspondent job at an American newspaper. My dream was always to be a foreign correspondent covering the Middle East, but I knew in order to get there I had to put in time and effort climbing the ladder, starting from smaller papers and covering local news and excelling in those jobs so I would get noticed by the big main newspapers.

In New York, I worked as a stringer for the metro section of The New York Times and attended graduate school at Columbia. I then went to The Providence Journal in Rhode Island as a junior reporter covering a small coastal town. My big break came when EgyptAir Flight 990 crashed into the Atlantic off the coast of my beat. I also scored my first foreign assignment to Cairo. Shortly after, The Newark Star-Ledger, New Jersey’s largest daily newspaper, recruited me to cover a big industrial city and its local government. I ended up cultivating what jokingly became known as the “Soprano’s beat” at the paper, writing long investigative pieces about the waste management business and the mob families who controlled it and their links to politicians. My coverage led to a grand jury investigation by the Attorney General’s office, indictment of the mayor and ultimately unravelled the largest waste management deal in U.S. history. I have to say, the single most career-altering event for me was September 11, 2001. I was a few blocks away from the towers when they collapsed, reported the aftermath from ground zero, and soon after I was dispatched to cover the war in Afghanistan. I kind of never came back home after that, traveling around the region from one conflict to the next. The Wall Street Journal noticed my work and hired me to cover the Middle East in January 2003. The Iraq war was pending so I was immediately sent to northern Iraq to wait for the invasion.

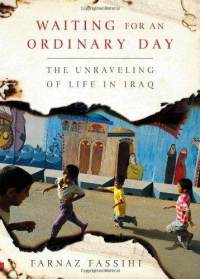

waiting for an Ordinary Day

You are the recipient of numerous awards in journalism for your coverage of the 9/11 attacks, the war in Afghanistan, and the Iraq war. Can you tell us about those awards and your book about the Iraq war “Waiting for an Ordinary Day: The Unraveling of Life in Iraq”?

All I can say is that I’m incredibly humbled and honoured to have my work recognized and awarded.

My book on the Iraq war is focused on how the war, from the American invasion to occupation and the civil war, impacted the lives of ordinary Iraqis and unravelled any sense of normalcy.

I felt that a lot of the media coverage focused on the military and political aspects of the war and not enough was written about the Iraqis. The narrative starts from my first visit to Baghdad in 2002 when Saddam Hussein was still in power and ends in 2006 when I left Iraq as the Sunni-Shiites civil war was starting. The book follows the lives of several characters including a Christian family struggling to survive, two young Shiites clerics who are rising stars of the new political order, my Sunni Iraqi staff resentful of the shifting landscape and also my own experiences as a young female journalist in Iraq.

Who would you name among some of your main sources of inspiration in your career?

I’ve been fortunate to have the friendship and mentoring of a number of acclaimed journalists who have generously shared their wisdom and advised me along the way. Christian Amanpour is an inspiration for her relentless commitment to bringing us the truth from conflict zones and Pulitzer-prize winning author Geraldine Brooks, formerly at The Wall Street Journal, for her masterful fiction writing that gracefully draws from her experiences as a reporter and non-fiction writer.

In the course of your career what have been some of the key challenges that you have encountered?

Every job has its challenges. I think writing stories from foreign countries in a way that can deeply resonate with American readers and break stereotypes is a continuing challenge. I’m always conscious of finding a way to humanize the story, put a face on war and uprisings so someone reading the morning paper with their coffee could pause and say that could be me or my child or my neighbour.

In conflict zones, security is always a challenge. You are always assessing the amount of risk against the value of the story you’ll get and often you have to consider other people; for example, a driver and translator you are also putting at risk. In Iraq, this was a daily dilemma for me; do I take the Iraqi staff to Fallujah even though I know he has two kids and could get kidnapped or killed for working with Americans? In Tehran during the 2009 uprising, I was getting tear-gassed and chased by security guards and having to make instant decisions on the spot about whether to linger or run away.

How do you think being an Iranian woman or a woman of Iranian descent has played itself out in your career?

I’ve viewed both being a woman and Iranian as an overall advantage in a very competitive business. After 9/11, many news outlets were seeking journalists who spoke Persian or Arabic, understood Islam and the culture of the Middle East and I was lucky to have those skills. Being a woman reporter in countries like Afghanistan and Iraq meant I could visit families at their homes and interview women, which is sometimes off-limits to male colleagues. I can also relate to many of the subjects that I write about in this region because I am from this part of the world and have also experienced upheavals, revolution and war.

This said, when I first started as a reporter in the U.S. I had to work harder to prove I was a versatile reporter and that my skills covering foreign politics could translate to reporting on domestic issues.

Being in the Middle East and having witnessed the Arab Spring first hand, how do you think the Arab Spring will impact women’s status in the Arab/Islamic world? Are you an optimist?

I think it’s too soon to make a definitive prediction about the future of women’s rights in the Arab world. The Arab Spring, in terms of the revolutions that led to change, has definitely empowered many young women activists and traditional women and given them a sense of having control over their destiny. But on the flip side, Islamist parties have won elections in Tunisia and Egypt and many secular women are worried that their rights could be curbed in a new constitution. In Iraq after the war, the secular family laws that were more favourable to women’s rights, such as child custody, divorce, and inheritance, were changed according to Islamic Sharia laws.

Ten years from now, what kind of an Iran do you envision in your mind?

I don’t think anyone can predict Iran’s future. Iranian politics have a tendency to always surprise. I can say that Iran is one of the youngest countries in the world and demographics will undoubtedly shape its future. The young, educated, and Internet savvy youth will continue to aspire for more democratic rights and the historical shifts we’re witnessing in the region will no doubt influence the future of Iran.