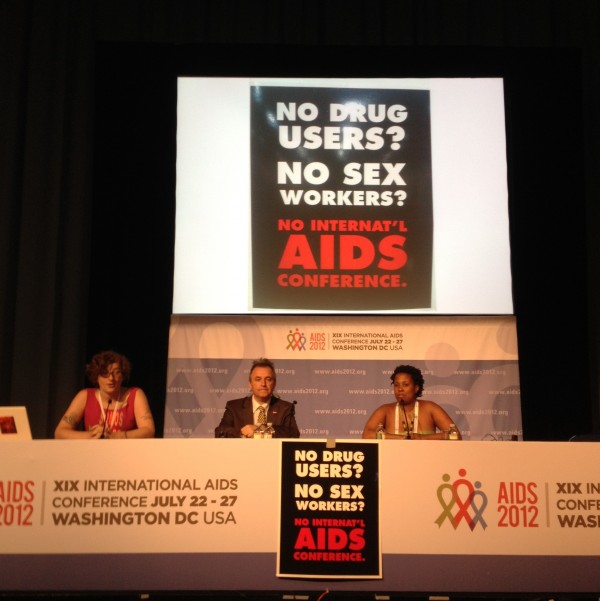

Activist Darby Hickey, Allan Clear of the Harm Reduction Coalition and Kelli Dorsey of Different Avenues at the International AIDS Conference in DC.

The International AIDS Conference is underway this week in Washington, DC. It is a historic occasion as this is the first time in 22 years the conference has taken place in the United States.

Protests dominated the last U.S.-based conference in San Francisco in 1990 because a law enacted in 1987 by Republican Senator Jesse Helms blocked HIV positive people from gaining entry to the United States. Concerned the politics overshadowed the scientific conference and frustrated at U.S. refusals to reverse the travel ban, the International AIDS Society (IAS) — the conference organizing body — refused to hold the conference in the U.S. while the ban was in place.

Two decades later, President Barack Obama lifted the travel ban. Shortly thereafter the IAS announced the conference would take place in Washington in 2012.

So it is a momentous day for U.S.-based scientists and advocates. The United States is the single largest donor to international AIDS funds, and American research has contributed significant advancements to the scientific toolbox to combat HIV.

The United States’ National AIDS Strategy, launched in July 2010, was also a landmark advancement under the Obama administration. The strategy highlighted that the epidemic is concentrated in certain high-risk groups, and said US response should be tailored to address those groups where the epidemic is most pronounced.

Sex workers and drug users are two of the most at risk groups for HIV and tend to have higher HIV prevalence than the general population. One Lancet study found sex workers to have HIV rates 14 times the general population.

But despite the lifting of the HIV specific travel ban, U.S. immigration law still bars drug users and sex workers from entering the United States.

Sex workers responded by organizing a separate conference, the Sex Worker’s Freedom Festival in Kolkata, India to coincide with the AIDS conference.

For sex worker advocates, though, the exclusion from the conference is just another example of sex workers’ voices being hushed and their needs swept under the rug.

A conference session brought together sex worker advocates from around the world to highlight how policies impact the human rights and health access of sex workers. Pye Jacobson, a Swedish advocate, denounced a widely touted program that criminalizes a sex worker’s clients rather than the — much more common — criminalization of sex workers themselves. “The state has made a law that tells everyone in society that we are victims, and something happens in society when you do this…what happens when people ask for services is they will be rescued. If they don’t want to be rescued they will be denied services.”

American advocate Melissa Ditmore took on the “anti-prostitution pledge” in the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Former president Bush’s landmark HIV funding mechanism prohibits funding “any group or organization that does not have a policy explicitly opposing prostitution and sex trafficking.” Ditmore says the policy undermines the very goals of PEPFAR. “By inadvertently promoting stigma against sex workers in health programs, the pledge in all its forms increases sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV infection.”

Before the conference, a United Nations funded and organized Commission on HIV and the Law released a report that calls for decriminalization of sex workers and safe working conditions with access to HIV services. The report simply compiled evidence that many public health workers had known long before. Advocates say it is politics, not public health, that influences the policies excluding sex workers.

Allan Clear, executive director of the Harm Reduction Coalition agreed and pointed to moralistic overtones in HIV debates in the US. “The concept of the involvement of people who use drugs or are sex workers is, pardon the pun, a foreign concept in this country.”