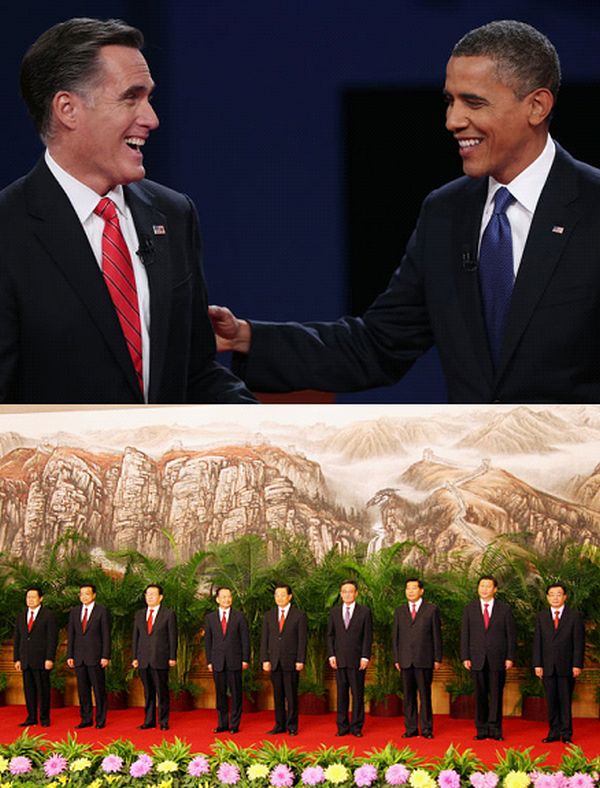

Top: Mitt Romney and Barack Obama at their Oct. 3 U.S. presidential debate. Bottom: The Chinese Communist party Standing Committee of the Political Bureau at the 17th National Congress, October 2007. Images: Los Angeles Times and Xinhua News Agency

The late theologian and political analyst Reinhold Niebuhr in his essay entitled “Optimism, Pessimism, and Religious Faith” wrote the following about Soviet Marxism: “But after many five-year plans have come and gone and it is discovered that strong men still tend to exploit the weak, and that shrewd men still take advantage of the simple, and that no society can guarantee the satisfaction of all legitimate desires, and that no social arrangement is proof against the misery which we bring about upon each other by our sin—what will come of this [Marxist ideology] optimism.” [Italics added] Niebuhr was a strong advocate of democracy, especially U.S.-style democracy, which he understood to be one means of checking and balancing the potential darker side of human nature and political power.

Assuming that all goes to plan, November will the month that the next presidents of the United States and China will be revealed. The U.S. election is scheduled for November 6 and will be followed two days later by the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. No one knows for sure who will win the U.S. election, incumbent Barack Obama or his challenger Mitt Romney.

Not so the case for China. It is highly anticipated that Xi Jinping will be the next Chinese president, and Li Keqiang will be China’s next primer. Indeed, it would almost be a bigger upset if this was not the case. The recent disappearance of heir apparent Xi Jinping from public view for almost two weeks led to a frenzy of speculation regarding what happened, or did not happen, to him. One could wonder why all the secrecy about Xi’s disappearance from public view. He did not meet with Secretary Clinton when she was in Beijing last month, and he canceled other scheduled meetings with Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and Danish Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt. The official Chinese reason was that Xi had hurt his back, surely then a simple phone call with Secretary Clinton would have done much to allay rumors regarding his whereabouts.

The point has been raised that China’s leadership transition is not going as smoothly as the CCP would have liked, and this time round, as Douglas Paal points out in the previous link “Seventy percent of the leadership is going to change. From the last meeting of the 17th Party Congress to the next meeting, a huge number of seats are going to switch—70 percent of the Politburo, 70 percent of the military commission, 70 percent of the Politburo Standing Committee, and on down through the system.” The potentially most public destabilizing variable regarding this transition concerns Bo Xilai, former party chief of the municipality of Chongqing, and until recently a rapidly rising star in Chinese politics. Bo was expelled from the Chinese Communist Party in late September and will now face criminal charges over corruption and bribery. His wife, Gu Kailai, has already been sentenced to life in prison over the murder of British businessman Neil Heywood, and his former chief of police Wang Lijun received fifteen years for his involvement in the case. It did not help that Wang applied for political asylum at the U.S. consulate in Chengdu earlier this year, a move that opened this case to public scrutiny.

The overarching theme seems to be emerging is that the current CCP mechanism for the transfer of political power is not very flexible in absorbing both external and internal shocks. The case for factional politics, as in any society, is proving to be a real inhibitor in Chinese politics, with a potential for far reaching consequences if consensus among party elites with vested interests cannot be achieved. In this case, it does appear that everyone is on the same page. Bo Xilai overstepped the mark and has been curtailed, and Xi Jinping is back in the public domain.

However, the point going forward is what different factions and interests will emerge amongst the CCP elites and how will they be resolved? As Niebuhr points out above, human beings, if left to our own devices, sometimes can and do exploit positions of power to the detriment of our fellow human beings. China faces a slowing economy, massive corruption, growing economic inequality, and more scrutiny from its own citizens. For the myriad of problems and challenges that will greet the next elected president of the United States, trying to keep internal party politics under wraps and in secret will not be one of them. The same cannot be said for the President Xi, and no doubt it will weigh heavy upon his mind and the minds of others going forward.