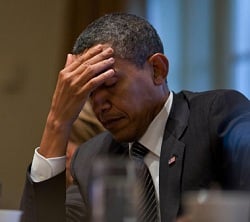

There are several updates to the key points I outlined in last week’s post about President Obama’s handling of the Afghan war.

There are several updates to the key points I outlined in last week’s post about President Obama’s handling of the Afghan war.

The first concerns the success of the surge of 30,000 extra troops that Mr. Obama announced in December 2009, most of which were deployed in southern Afghanistan. As I noted, one of the significant nuggets in Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s informative but depressing new book about U.S. policy in Afghanistan is that many in the White House privately concede that the troop buildup has been a failure. An article in the New York Times yesterday reports the same thing, quoting a senior administration official as saying:

When you look at the map in two years, the Taliban are going to be controlling big, rural swaths of the south. And that’s something no one wants to talk about very much.

Underscoring this point, the Times goes on to say:

A senior military official said that before the troop increase there were roughly 2,000 insurgents moving regularly across the mountainous border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. And after the increase was over, he said, there are still about 2,000.

The surge’s failure likely accounts for the administration’s reticence in talking up its management of the war, except to remind all concerned that the conflict will soon come to end (at least for the Americans and their NATO partners). Vice President Joe Biden recently declared this position so emphatically – “We are leaving [Afghanistan] in 2014, period” – that he called into question the U.S. commitment to reaching agreement with Kabul on retaining a sizeable residual force beyond that date.

Given how Americans – including an increasing number of Republicans – are fatigued with a decade of war in the Greater Middle East, the administration’s stance might make for smart domestic politics. But regularly declaring that “the tide of war is receding” – as the president did earlier this year when unveiling his new defense strategy and which the 2012 Democratic National Platform trumpeted – does have adverse ramifications for other foreign policy goals.

As a previous post argued, the president’s rhetoric undermines the credibility of his tough talk vis-à-vis Iran’s nuclear ambitions. And emphasizing that America is headed for the exits in Afghanistan gives New Delhi little reason to cooperate on the Iran issue. I’ll have more to say about these themes in a future post.

A second update concerns the argument that Mr. Obama’s management of the Afghan conflict is seriously plagued by institutional dysfunctions, including personal antagonisms, poor decision-making and the lack of rigorous policy follow up. Rosa Brooks, who earlier served as an Obama appointee in the Pentagon’s policy shop, reinforces this point in a new critique of the administration’s “broken foreign policy machine.” She writes:

[T]o a significant extent, President Obama is the author of his own lackluster foreign policy. He was a visionary candidate, but as president, he has presided over an exceptionally dysfunctional and un-visionary national security architecture — one that appears to drift from crisis to crisis, with little ability to look beyond the next few weeks. His national security staff is squabbling and demoralized, and though senior White House officials are good at making policy announcements, mechanisms to actually implement policies are sadly inadequate.

A follow-up note by Brooks, along with concurring comments by former and present administration staffers, is located here.

A third update regards a point that is increasingly gaining currency: For all of Mr. Obama’s skills at public rhetoric, he is seriously deficient at forging strong personal connections with other leaders, either at home or abroad. Neera Tanden, formerly an Obama administration official who currently runs the Center for American Progress, a think tank closely aligned with the White House, is the latest to join the chorus:

The truth is, Obama doesn’t call anyone, and he’s not close to almost anyone. It’s stunning that he’s in politics, because he really doesn’t like people. My analogy is that it’s like becoming Bill Gates without liking computers.

Of course, the art of presidential buddy-making is tricky. Two quick examples: Richard Nixon had a deep friendship with Pakistani President Yahya Khan, but it – along with Nixon’s intense antipathy for Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi – distorted U.S. policy during the 1971 Bangladesh War and contributed to a decades-long chill between Washington and New Delhi. George W. Bush had solid ties with Tony Blair of the United Kingdom and (famously) Junichiro Koizumi of Japan. Yet his affable nature also led him to misjudge Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

Still, given how so much of the military surge hinged on coaxing Hamid Karzai into stepping up his own governance efforts, Mr. Obama’s failure to reach out to the Afghan leader is remarkable.

This commentary was originally posted on Monsters Abroad. I invite you to connect with me via Facebook and Twitter.