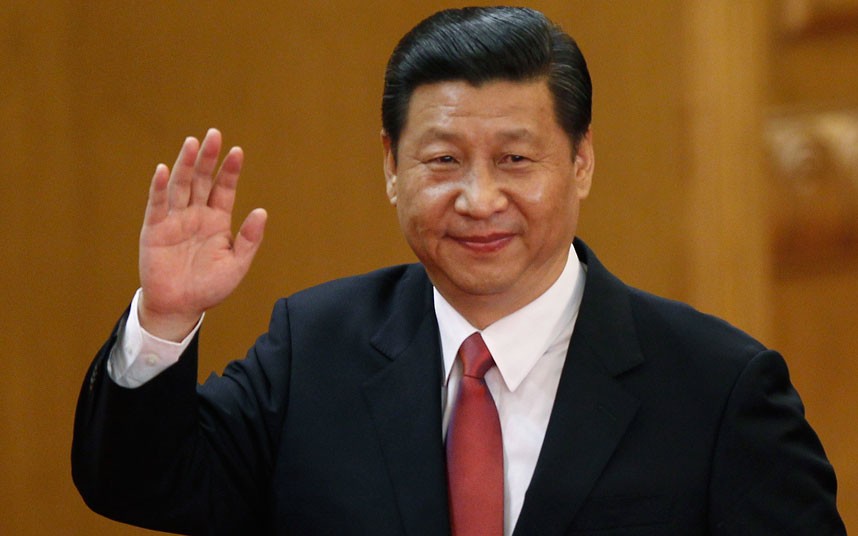

Xi Jingping, new leader of China. Despite increased hopes for democratic reform, the chances of it actually happening are slim. Photo credit: Vincent Yu/AP

Presidential politics in China are pretty predictable. About once a decade its Communist Party votes for a new leader, who becomes the new president. The process is shrouded in secrecy, and not much is known about the new boss until he (and it’s always been a “he”) takes office. There’s also always some debate and conjecture about whether the new guy will actually spearhead reforms that would finally move the world’s most populous country closer to democracy. The answer is typically no.

All of these things happened last week when Xi Jinping, son of a Communist revolutionary general who the world knows very little about, become the new General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (he officially becomes President next March). And despite what the Washington Post characterizes as “widespread clamor for reform,” it does not appear that much movement toward democracy is likely.

Xi has followed the leadership precedent by not saying much about what he would do as president. While he did say the word “reform” 86 times in a speech to the party last week, but that word can have many meanings in China. Rarely does it mean “moving toward anything resembling a Western-style multiparty democracy.” Even if Xi is waiting to consolidate power and then institute political reform–as some think–all signs point to that reform working to strengthen the party’s grip on power. Any moves toward making the political process more open would be marginal and only to hold dissenters at bay.

Those in China seem to have realized (however reluctantly) that with the new president they will see more of the same. Even though a common opinion is that Xi is more like a reformer than outgoing leader Hu Jintao, as economist Mao Yushi starkly puts it, “China is a country under dictatorship. But the new leadership group I don’t think will take active measures to change the situation. It’s too difficult.”

Some reformists are hopeful that China’s new premier (#2 in the hierarchy), Li Keqiang, will be a voice for change within the party. Li rose up through the party ranks without a political pedigree, and went to Peking University along with several prominent pro-democracy activists. Yet Li has also been a loyal party member through the years, and prevailing thought is that any attempts he might make toward democratic reform will be quashed and Li isolated.

Also unclear is how the new leadership will get along with China’s neighbors (Japan) and rivals (the U.S.). As the country’s economic growth slows, economic concerns remain heightened.

That’s a lot of uncertainty for a very delicate political and societal situation. It’s hard to say how long “more of the same” will work for China’s Communist Party. At least for now they don’t seem to be going anywhere.

But 10 years from now, when the next leader is chosen, will their dominance remain? It seems like an increasingly challenging proposition as each year of the 21st century goes by.