Spokesman for new Syrian National Coalition accuses US of “empty promises’ about the delivery of weapons to rebels

The Syrian rebels, or opposition, or the Syrian National Coalition (the name this motley assembly of Sunnis, Salafists, jihadists, and foreign insurgents) agreed to take on in Doha as a prerequisite for U.S. support (money PLUS guns), successfully launched a surface to air missile (SAM) about ten days ago, bringing down a Syrian government aircraft. Reported by the BBC, the news caused hardly a stir. Word was that the shoulder-hoisted weapon came from Iran, but who really knows?

The fact is that the camel’s nose is definitely under the tent, and the rowdy bunch of Sunnis et al challenging Assad’s Shiite/Alawite regime are loaded for bear. Yes, they’re gunning for the Russians, Assad’s backers, that’s a fact. But will there come a time when they’re also gunning for us? With those same surface to air missiles?

On December 12, the U.S. joined the Gulf States, France, and the U.K. in endorsing the Syrian National Coalition as the “sole representative of the Syrian people,” an announcement that President Obama made live and on TV with the admission that a “tiny part” of that legitimate, Syrian “government in waiting” is constituted of al Qaeda “terrorists.”

Do tell.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but aren’t these the guys who killed roughly 3000 Americans when they flew hijacked planes into the Twin Towers and set the Pentagon on fire?

Of course, if they’re only a “tiny part” of the Syrian group to whom the U.S. is giving millions in support and maybe lethal weapons, what the heck?

The important thing is to support the House of Saud (for oil) and eliminate Iran’s only buddy in the Mideast (for Israel). Oh, oh, wait…there’s also that multilateral, “good neighbor” thing that says we have to support our NATO partners in Europe (Libya?) who REALLY need the oil, and the goodwill of the Gulf States, (I’m told it costs 80-100 euros to fill up on the continent) to struggle on through fiscal catastrophe.

And then there’s politics.

Let’s chase those Russians out of Syria the same way we did in Afghanistan. That worked. And it will work even better, won’t it, when ISAF forces leave Dodge in 2014 and a western-supported government operating out of Kabul…disappears?

It’s ok.

Afghanistan also has a “government in waiting.”

The Taliban.

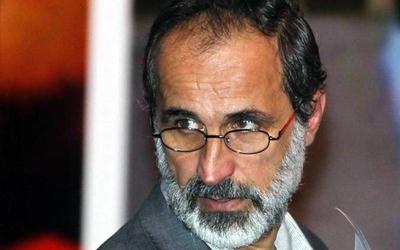

No matter. Given the fact that I always seem to be living near an international airport, the question of what interests the U.S. might have in the mideast that would justify support for “the Wild Bunch in Syria” has been bothering me more than usual. But before I could blog my way through the problem, someone else did it for me: Aaron David Miller, who writes a column for foreignpolicy.com.

It’s a great read, simple, true, and unbelievably, well, believable. I don’t know who this man is, (his bio says he’s a scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and that his new book — “Can America Have Another Great President?” — will be published this year), but his four-point explanation of continuing U.S. involvement in the mideast should be required reading for anyone who doesn’t want to send more taxpayer monies or US troops to shore up the cockeyed Mullah-managed agenda of sectarian wingnuts across the Middle east.

The article below (focus on “oil” and “preventing another 911” and “human rights?–fuhgeddaboudit”) belongs to Miller, who appears to have hit a big, bad, and hugely misunderstood nail right on the head:

The Politically Incorrect Guide to U.S. Interests in the Middle East

BY AARON DAVID MILLER

AUGUST 15, 2012

Sorry, folks: America just doesn’t care about freedom or Arab-Israeli peace all that much.

Foreign policy, including the use of military power, isn’t an end in itself. It consists of tools and instruments designed to achieve specific and hopefully well-thought-out ends. Those ends — let’s call them interests — are theoretically supposed to drive a country’s foreign-policy strategy. Sounds pretty simple, right?

So what are America’s interests in the Middle East? Are there core goals and priorities that are more important than others? Does the country pretend certain things are more important than they really are? And how do you think it is doing in protecting those interests?

These are really good questions, and they’re not asked nearly enough. One reason is that since 1945, when the United States began to get its feet wet in the region, largely as a consequence of oil, Israel, and the Russians — that complex triumvirate of things it was trying to either protect or guard against — its core interests have remained pretty much the same.

Today, if you take the Russian bogeyman out of the picture (sorry Mitt), add Islamists and counterterrorism, and subtract a few Arab dictators and authoritarians, U.S. interests remain pretty much the same.

And despite all the charges of bias, dysfunction, and incompetence leveled at the United States, the country has actually done a pretty good job at protecting those interests. The Soviets never really made inroads in the Middle East, and eventually collapsed. The oil kept flowing from the Persian Gulf. And there was even progress — under American auspices — on the Arab-Israeli peace process.

Granted, the United States had a couple of oil shocks (1973 and 1979) and a half dozen Arab-Israeli wars, and America’s Arab street cred is way down because the country has cut a devil’s bargain with more than a few authoritarian rulers and because it staunchly supports Israel.

But hey, you know what? It’s not so easy being a great power. And it’s really hard to keep everybody happy. If you want unconditional love and affection, get a puppy.

Indeed, had it not been for President George W. Bush’s trillion-dollar social science project in Iraq and President Barack Obama’s initial tendency to create inflated expectations on both the Israeli-Palestinian issue and what the United States could do to bring democracy to the region, America would even be in better shape.

So what are America’s vital national interests in the region today — the matters it considers the core of its relationship with the Middle East?

Listen to how Obama answers the question. In a major speech in May 2011 dealing with what was then a more hopeful unfolding of the Arab Spring, he said the following:

“For decades, the United States has pursued a set of core interests in the region: countering terrorism and stopping the spread of nuclear weapons, securing the free flow of commerce and safeguarding the security of the region, standing up for Israel’s security, and pursuing Arab-Israeli peace.”

But Obama then went on to add that those interests were insufficient to constitute America’s entire foreign-policy strategy. “We must acknowledge that a strategy based solely upon the narrow pursuit of these interests will not fill an empty stomach or allow someone to speak their mind,” the president said.

I’d give the president a B-minus for historical accuracy here and a C for honesty about American priorities. Only relatively recently has the United States been really serious about counterterrorism — it has cherry-picked those countries that it doesn’t mind having nukes (Israel, India) and those of much greater concern (North Korea, Pakistan, Iran). And though the peace process has been a priority at times, it has mostly been pursued haphazardly.

The president’s views on democracy promotion also represent a real contradiction. By trying to wrap the pursuit of more traditional interests in a prettier box, Obama doesn’t do himself or us any favors. Indeed, he raises the expectation — his specialty — that the United States, true to its democratic values and principles, will now rise up to decry tyranny, oppose the heavy hand of the authoritarian, and champion the popular will against oppression.

The only problem is: The country doesn’t. The perpetuation of this fiction sets the United States up for charges of hypocrisy and carries the potential to undercut the very interests the president identifies as core.

To keep commerce free (I think Obama means oil), the United States supports the authoritarian Saudi kings. To keep the region secure, it backs the repressive Khalifa monarchy in Bahrain, which gives the U.S. Navy’s 5th Fleet the port access that allows it to project power across the Gulf. And to stand up for Israel, the United States gives the Egyptian military $1.3 billion per year to protect the peace treaty and turn a blind eye while the generals protect their praetorian privileges. As far as championing the rights of the Arab peoples, see America’s largely hands-off policy on Syria — correct though I believe it to be.

I’m not complaining, mind you, just reporting. But the United States needs to be clear and stop pretending. There are certain things in this region it really cares about and that resonate powerfully at home, and others that don’t — and in any event are less susceptible to American influence, power, and persuasions.

Here’s the politically incorrect and inconvenient version of American interests in the region. The United States has at least four vital national interests that it really cares deeply about. It is prepared to use force to protect all of them.

1. Stopping an attack on the continental United States with conventional and unconventional weapons. This is the big one. The organizing principle of a country’s foreign policy is protection of the homeland. If you can’t do that, you don’t need a foreign policy. Americans are safer since the 9/11 attacks — but not safe. There are still transnational groups that want to inflict catastrophic harm on the United States. The country will continue to spend the time and resources in an effort to stop them. The U.S. military will whack bad guys with drones whenever it can, regardless of the protestations of local governments.

2. Energy security. The good news for America is that it’s weaning itself off Arab oil. The bad news is that oil is a single market. Supply disruptions and the challenge of making sure Persian Gulf oil doesn’t fall into unfriendly hands — or stop flowing entirely — will be a core interest for as long as America and the world are dependent on hydrocarbons.

Want to worry about something? Worry about the House of Saud coming down. Oil is useless unless sold, but a regime change in Riyadh that triggered lengthy convulsions would be devastating for America and the world economy. So, staying true to the principles it really doesn’t have, America will push what I call the “wink and nod” brand of reform from the Saudis (and also the Bahrainis, and the Kuwaitis, and the Qataris, and the Emiratis). And it’ll use force to keep the Strait of Hormuz open and to protect that tried-and-true democracy in Saudi Arabia.

3. Supporting Israel. I can already hear the “what do you mean supporting Israel is a core interest?” crowd rumbling in the back. Let the Israelis fend for themselves, it says. They don’t deserve any special status, particularly when they ignore U.S. interests.

The fact is, America has allowed the “special relationship” to become far too exclusive and one-sided, and that’s not good for Israel or America. Obama isn’t all that enamored about the special bond either and would like to reset it — but he can’t do much about it at this particular political moment.

But none of that makes the case for supporting one of the few democracies that emerged in the wake of World War II any less compelling. Strict realists question the whole values argument, particularly given the Israeli occupation. But support for the security and well-being of Israel, with all its imperfections, is in accord with the broadest conception of the American national interest — supporting like-minded societies.

Israel also resonates powerfully at home in political terms, and that’s nothing to be ashamed of or defensive about. Even factoring in the power of the pro-Israeli community, the U.S.-Israel bond could not have survived for this long without the support of millions of Americans — not just Jews and evangelicals — who believe in it too. In a democracy, you need a sustainable domestic base for any long-running policy. There’s just no way U.S. support for Israel would have lasted 60-plus years if enough Americans didn’t sign off on it.

There’s a fourth point that I reluctantly put in this category of vital national security interests — though I’m not at all sure about it, particularly on whether the United States should be prepared to use military force.

4. Stopping Iran from getting the bomb. I have to be honest: I thought a good deal about not putting this one in the core category. Don’t get me wrong; you’d have to be interminably obtuse to conclude that Iran with nukes would be anything other than a disaster. It would raise regional tensions, buck up Iran’s regional ambitions, escalate the Israeli-Iranian covert (and maybe overt) war, and probably set off a regional arms race.

And there’s no doubt the Obama administration is exerting great effort to stop or delay Iran’s program. It has implemented powerful sanctions and embarked on negotiations with a weakened but not chastened Islamic Republic, as dubious as their prospects are.

Still, I’m not at all persuaded the president’s heart is in this one. On Iran, he’s clearly the “not now” president — and I suspect he would just like the whole issue to go away. He and the mullahs probably share a common goal: stop or delay an Israeli strike for as long as possible. The president doesn’t want to see Iran with nukes, but he worries even more about an Israeli or American military strike

The Israelis may well force the president’s hand at some point — striking Iran and triggering a U.S. intervention too. But this president will go to great lengths to prevent that. He knows that hitting Iran’s nuclear sites will only set the program back a couple of years. Perhaps he’s prepared — and his successors would be too — for a strategy of striking Iran’s nuclear facilities every so often, like some grand game of whack-a-mole (the Israelis call it “mowing the lawn”). But I’m not sure that’s a sustainable policy.

The fact is, there’s probably only one country that can stop Iran from developing a nuclear weapons capacity, and that’s Iran. But I’m not at all sure Tehran will determine that the costs of its nuclear program are prohibitive. Indeed, the fall of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime will only sharpen Iran’s sense of vulnerability and accelerate its quest for a weapon.

If Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini hadn’t overthrown the shah in 1979, Iran would be a nuclear weapons state today. Why? Because the four countries that have developed nuclear weapons in the past several decades — Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea — are all fundamentally insecure. They were determined to acquire nukes and had the means and motivation to pull it off. Iran is the poster child for insecurity, but it’s even more than that. Throw in its conception of itself as a great power, its regional ambitions, and its grandiosity, and poof — you’re on the road to Nukeville.

The odds that the United States can stop the mullahs from acquiring the capacity to produce a nuclear weapon, should they truly want one, are long indeed. With regard to military action, the risks are probably overstated. It’s the efficacy that bothers me. Will a military campaign work? Does America try some eleventh-hour, high-level secret talks with Iran first? Great questions; no answers. But the moment is approaching later this year, or early in 2013, when Israel and the United States will probably face a choice. Bomb, or accept the bomb.

The Rest Is Discretionary

But wait, you say, what about America’s other interests, particularly the peace process and democratization?

Great questions. Let me give you some harsh answers. Watch the U.S. government’s hands on these two; don’t listen to its words. And what that disconnect tells me is that however much the United States says it cares, it really doesn’t all that much.

On the issue of a conflict-ending agreement between Israelis and Palestinians, wake me up when the current Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority get serious about doing something real. Every previous breakthrough was preceded by some act — positive or negative — that the locals initiated and that gave Washington the means and motivation to intervene successfully. Unless that ownership is present, the United States should stop worrying about this plan or that and stop pretending that it can somehow fix this.

On the issue of the Arab Spring — or Islamist Winter, depending on your viewpoint — it’s going to be a very long movie. The United States should do what it can to help but stop inflating its rhetoric and realize that it’s in no position to act decisively. The country is still involved in a devil’s bargain with authoritarian monarchies in the Gulf, military elites in Egypt, and a strongman in Iraq (not to mention a corrupt regime in nearby Afghanistan). Nor did it ever have the capacity or the will to remake these lands. The fact is, Arabs own more of their own politics now than ever before. And that’s a good thing.

If America wants to pretend to the rest of the world that it’s serious about Arab-Israeli peace or that it’ll stand up to defend nascent Arab democracies, that’s one thing. All governments dissemble and use idealized arguments to package their policies.

But there are certain things the United States cares about and others it doesn’t — certain issues it’s prepared to do something about and others it chooses not to. At the very least, we should stop fooling ourselves about what those really are.