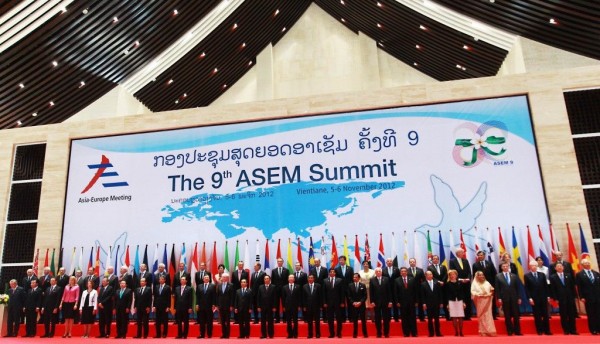

EU and Asian Leaders at the 9th ASEM Summit hosted in Laos, November, 2012 Image: gov.ph

“In particular, I strongly believe that Europe should join the United States in increasing and deepening our defense engagement with the Asia-Pacific region.” These words are from outgoing U.S. Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta in his final overseas address to an audience at King’s College, London, delivered on January 18. This raises the question: Can Europe bring any military assets to the Asian theater, or even more narrow, what European countries can afford to contribute to Asia’s security?

Clearly, NATO is the preeminent multilateral security alliance in the world, as has been witnessed by a number of salient actions since the end of the Cold War, most recently Libya and Afghanistan. There is no doubt that the alliance, or members of the alliance, will be called upon to engage in operations concerning Syria and Iran, should these increasingly tense situations thus evolve. And recent French operations in Mali, with support from the United States and other NATO partners, indicate that European military powers will be busy for the foreseeable on their own periphery, a policy that is supported by the United States as its continues its rebalance towards the Asia-Pacific. Libya is the example of this, while the United States was still the most important actor in that campaign, there was a concerted effort by U.S. officials to step back and let EU/NATO and other actors assume a more leading role, and not the United States, as had always been the case in previous campaigns. And that is why, in part, it took so long for the Gaddafi regime to collapse.

During his speech, Panetta explained the reasoning behind Europe joining the United States in engaging with Asia. In his words: “More importantly, Europe’s economic and security future is – much like the United States – increasingly tied to Asia. After all, the European Union is China’s largest trading partner, ASEAN’s second-largest trading partner, and ranks third and fourth with Japan and South Korea.” Moreover, on issues of global governance, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, human rights, democratic governance, open sea lines of communication and a rules-based international order, both the United States and Europe are on the exact same page, paragraph and sentence. Period.

In a lead essay in the September/October 2009 issue of Foreign Affairs entitled “An Agenda for NATO”, former National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski alluded to the possibility of NATO reaching out to China, Japan and India to “perhaps also take the form of joint councils, which could promote greater interoperability, prepare for mutually threatening contingencies, and facilitate genuine strategic cooperation. Neither China nor Japan nor India should avoid assuming more direct responsibilities for global security, with the inevitable shared costs and risks.” Brzezinski foresaw a NATO potentially as the “hub of a globe-spanning web of various regional cooperative-security undertakings among states with the growing power to act”. However, there may be two, if not more, problems with this paradigm. Number one is who would lead, (this was a problem for NATO when the U.S. wanted to extract itself from the Libya operation), and second, can the main Asian actors cooperate in such an institution. (Obviously, the U.S. has always been the leader in NATO, and I recently heard Professor John Mearscheimer, author of The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, comment that it should have been NATO, not the EU, that received the Nobel Peace prize last year.)

At face value, there does seem little that European actors can contribute to Asia in terms of military assets. Admittedly, the United Kingdom, an enduring and staunch ally of the United States, is a member of the Five Defense Powers Agreement with Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand and Singapore, and France does have security responsibilities for its territories in French Polynesia. The U.K. and Australia signed the Australia-United Kingdom Defense and Security Cooperation Treaty on the same day that Secretary Panetta was giving his speech in London, and the U.K. has made clear its intention to focus more of its diplomatic focus to Asia in a speech by U.K. Foreign Minister William Hague last year in Singapore entitled “Britain in Asia.”

On a regional scale, the still evolving European External Action Service under the leadership of Lady Catherine Ashton has made some positive moves into Asia signing the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation with ASEAN. Lady Ashton and U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton issued a Joint EU – U.S. statement on the Asia-Pacific Region last July at the ASEAN Regional Forum, and this year for the first time, Europe will have a seat at the East Asia Summit. For a full list of Europe’s engagement in Asia last year, read the EEAS report for 2012 which highlights Europe’s engagement with Asia from the Free Trade Agreement with South Korea (Negotiations were initiated with India, Singapore, Malaysia, and Vietnam, and exploratory talks continued with Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand) to Overseas Developmental Assistance (the EU is the world’s largest aid donor) and EU engagement with Burma.

Secretary Panetta’s final overseas speech, like his predecessor, was in Europe. However, in stark contrast to Secretary Robert Gates’ speech, Panetta praised the role of NATO (and Europe) in contributions to global security acknowledging that “The third pillar for building the transatlantic alliance of the 21st century must be a determined and proactive effort to build strong partnerships with nations and security organizations in other regions of the world.” Panetta’s presentation was very different in tone to the speech by Gates where he openly questioned if “America’s investment in NATO [is] worth the cost.” Last year, NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen signed the NATO-Australia Joint Political Declaration with Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard on a visit to Australia, the first vist by a NATO Secretary General to that country. It is worth noting here that NATO does have select countres, primarily in Asia that it deems “partners across the globe.” The countries in question are: Australia, Japan, the Republic of Korea, New Zealand, Pakistan, Iraq, Afghanistan and Mongolia.

However, the fact remains that European nations are very unlikely to contribute military assets to Asia, and as highlighted above, Europe’s periphery has more than enough potential contingencies not to do so. Having said that, the United States and Europe as the world’s two largest economies, has much to gain from preserving the fundamental structure of the current international order, and welcoming new emerging actors into the rules-based, liberal trading paradigm. To that end, it is more probable that they could have greater impact on influencing the behavior of emerging Asia actors, namely China, by jointly coordinating and addressing issues of mutual concern that they have with China, and using relevant mechanisms such as the World Trade Organization, to resolve those differences. Europe, in Secretary Panetta’s own words “should join” the United States in its “rebalance to Asia,” though maybe not just yet in the military realm.

Endnote: Both NATO and the EEAS were swift in voicing their strong condemnation to North Korea’s test of a nuclear device on February 12.

Damien Tomkins is Project Assistant at the East-West Center office in Washington, D.C. where he contributes research and content to the Asia Matters for America initiative and coordinates the Asia Pacific Bulletin publication series. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and not of any organization with which he is affiliated.