Today is 60 years since the death of Joseph Stalin. How do we know this? Well, it’s on the front page of the BBC, there’s an article in the Telegraph, Reuters, the Atlantic and pretty much everywhere else. Except Russia itself, that is, where the event hardly attracted any attention whatsoever.

It was not on the front page of any of the major papers, from the populist tabloid Komsomolskaya Pravda to the liberal Gazeta.ru to the opposition Novaya Gazeta. At best, it was a story tucked away in the margins, overshadowed by the arrests in the Bolshoi acid scandal and Russia’s tougher stance on North Korea.

Many of the stories in the western press follow this familiar template: Stalin continues to live on in Russia, his legacy egged on by the authoritarian Putin.

A representative passage from Reuters:

“Support for Stalin has risen in Russia since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 gutted the social safety net, damaged national pride and left many Russians longing for the perceived order and stability of the Communist era.”

Most “commemorative” articles are lazy journalism: just recycle old material from previous anniversaries, and you’re golden. But the latest crop of Stalin pieces is particularly bad.

Perhaps out of wishful thinking or the belief held by many casual observers of Russia that Putin’s government must obviously go hand in hand with an insidious Stalinism, most of these articles ignored an interesting development: Support for Stalin may have risen since 1991, but it has actually fallen during Putin’s reign.

According to yesterday’s poll by the Levada Centre, the fraction of people who believed that Stalin was “undoubtedly positive” halved from 18 percent in 2003 to nine percent today. Half of Russians continue to harbor more or less positive attitudes to Stalin, but the cooling of the love is noteworthy.

What’s more, the poll also contradicts another widespread notion: That seemingly pro-Stalin stunts by the government, such as the plan to rename Volgograd back to Stalingrad, have served to rehabilitate the dictator. Nearly half of respondents called the renaming an attempt to whitewash Stalin’s repressions and detract the public from corruption scandals and other pressing concerns.

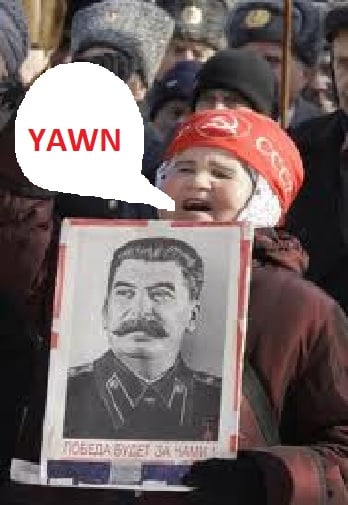

But mostly, Stalin these days elicits a shrug. Young Russians I have spoken to just don’t care about him; for them, the entire USSR belongs to some prehistoric period. As a Georgian woman was quoted in the Stalinist-trawling BBC article as saying:

“Young people don’t like Stalin, of course [because] our young people are not interested in history.”

Perhaps the only people clinging to Stalin’s legacy are Western journalists, devoted to the idea that the mustachioed murderer’s ghost still haunts Putin’s Russia when in fact, he’s long become irrelevant.