The following post is based on an address I delivered at the Shanghai Maritime Strategy Research Center two weeks ago.

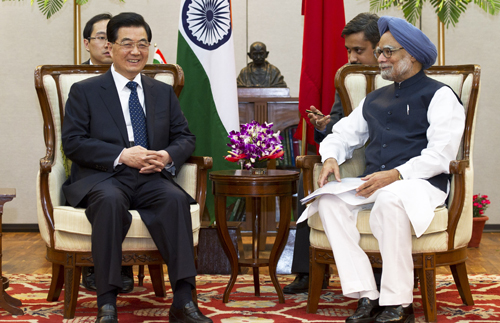

The punditry gods were smiling when Beijing and New Delhi declared 2012 as the Year of Sino-Indian Friendship. After all, it was a most curious designation, and not just because 2006 had received the same appellation with little to show for it. Indeed, the Chinese that year revived their territorial claims over all of Arunachal Pradesh, a state in India’s remote northeast that lies along their long-contested Himalayan border and which Beijing now insists on calling “South Tibet.” Even more striking was that the Chinese chose to make this an issue on the eve of President Hu Jintao’s visit to New Delhi in November 2006, the first such visit by a Chinese head of state in more than a decade and one that was meant to highlight growing bilateral cooperation.

Given this track record, the 2012 designation was all the more peculiar, especially since it coincided with the 50th anniversary of the 1962 border war between the two countries. The event, mostly ignored in China, reanimated bruised memories in India and two former foreign secretaries, Shyam Saran and Kanwal Singh, took to the opinion pages to warn (here and here) about China’s aggressive designs. Representative of the media reaction was the Deccan Herald, a Bangalore-based newspaper, which cautioned its readers that “China is a hydra-headed monster with massive expansionist plans across South Asia.”

The uneasy juxtaposition of the dates neatly encapsulated the contending factors – increasing economic cooperation mixed with ulcerating historical animosities and an intensifying strategic rivalry – that tug at New Delhi’s relations with Beijing.

True, the friendship year began in congenial enough fashion. A week into 2012, Shivshankar Menon, India’s national security advisor, delivered an address at the Chinese embassy in New Delhi, rejecting the notion that the countries “are bound to be strategic adversaries. Instead, he emphasized the opportunity for the two “to work with others to shape benign international outcomes.” And in an opinion piece published in the Hindu newspaper a few days later, Dai Bingguo, Beijing’s foreign policy czar, proclaimed “China’s tremendous sentiment of friendship towards India” and predicted a coming “golden period” in bilateral affairs.

But as 2012 drew to a close, four events aptly illustrated the contradictory impulses in the relationship. The first was in November when high-level delegations from both governments convened in New Delhi for the second session of their recently established strategic economic dialogue. In 2010, China became India’s largest trading partner, with two-way trade now totaling some $75 billion and both sides have plans to elevate trade flows to the $100-billion mark by 2015. And if a recent report by the Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry is right, Beijing and New Delhi could well form the world’s largest trading combination by 2030.

The Indian side used the economic dialogue to reiterate calls for greater Chinese investment in Indian infrastructure projects and a number of deals amounting to some $5 billion were struck between Chinese and Indian companies. The dialogue’s Indian co-chair stressed how his country can “certainly benefit by studying the Chinese experience in the building of infrastructure and handling of urbanization.” Since Indian capacity for funding infrastructure on its own is so deficient, New Delhi is looking for help from China. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh made this pitch to Premier Jiabao Wen at the Rio +20 summit in June, and he repeated the plea at the ASEAN Summit meeting in Phnom Penh in November. The Indian government also is encouraging Chinese participation in the new manufacturing zones it is setting up throughout the country. For its part, Beijing has mooted an interest in jointly working with New Delhi to expand regional development in South Asia, one of the world’s least economically integrated areas.

All of this followed indications that Beijing may be looking to reset its relations with New Delhi. During a visit to the Chinese capital last summer, then-Executive Vice Premier Li Keqiang made a point of telling Indian Foreign Minister S.M. Krishna that the Sino-Indian equation would be the important bilateral relationship in the 21st century. Li’s phrase is a virtual echo of the Obama administration’s regular formulation about Washington and New Delhi constituting “an indispensable partnership for the 21st century.” Beijing has also upgraded its ambassador in New Delhi to vice-ministerial status, and there is increased speculation that China is dumping its policy of maintaining “strategic equilibrium” between India and Pakistan in favor of giving greater emphasis to New Delhi.

Yet just three weeks after the conclusion of the economic dialogue, another prominent gathering in New Delhi highlighted the growing geopolitical competition between the two countries. With an eye on Beijing’s assertive behavior in the South China Sea, Southeast Asian leaders used an unprecedented summit meeting with Indian officials to call for a greater Indian role in the region. The meeting produced plans for a new “strategic partnership” aimed at enhanced diplomatic, economic and security cooperation between India and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Indeed, in the run-up to the meeting, the chief of the Indian navy proclaimed New Delhi’s readiness to use military force to protect its oil-exploration interests in an area off the coast of Vietnam that China claims as its own.

These events illustrate how East Asia has emerged over the past few years as a new arena for strategic rivalry between New Delhi and Beijing. Most striking in this regard is the growing intensity of Indian security and economic cooperation with Japan. The two countries conducted their first bilateral naval exercises last year off the Japanese coast and held an inaugural dialogue on maritime security earlier this year. With Shinzo Abe, now ensconced for a second time as prime minister in Tokyo, putting special emphasis on collaboration with India, this bilateral equation is starting to become an important feature of the Asian regional balance.

New Delhi also has moved to solidify security relations with Hanoi, including the possible provision of military assistance, and to strengthen its influence in Myanmar, which China and India have long regarded as an arena for geopolitical jousting. And concerned about the growing profile of the Chinese navy, India has started a formal dialogue with Australia and Indonesia on regional security.

At the same time ASEAN leaders were gathering in New Delhi, a third event – regarding a dispute between an Indian company and the Maldives government over the management of the airport in Male – reinforced concerns about Beijing’s encroachment in its own neighborhood. A coup in February 2012 ousted a pro-Indian leadership in the strategically-placed archipelago nation and New Delhi is reported to believe that the new regime abruptly terminated the lucrative airport contract at the behest of the Chinese, who want to bulk up their presence in the Indian Ocean in order to guard oil shipments coming from the Middle East. Just weeks before the termination of the $500-milllion contract, which represented India’s largest investment project in the Maldives, Beijing pledged a $500-million economic assistance package for the country. And a week after the contract was voided, China and the Maldives announced plans to strengthen military ties. All of this follows renewed concerns over Beijing’s increasing influence in Sri Lanka and Nepal, and were amplified yet again in early 2013 when Pakistan turned over management of Gwadar, a strategic port at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, to a Chinese company.

The growing contests for power and influence in East Asia and the Indian Ocean amply demonstrate how India and China will bump into each other as they grow in power and aspiration. But a fourth event in late 2012 illustrates that the true fault line in bilateral relations remains the 60 year-old acrimony over the Indo-Tibetan frontier. Beijing’s issuance of new passports displaying a map showing a range of contested territories throughout Asia (including Arunachal Pradesh and Aksai Chin) as belonging solely to the People’s China brought forth Indian accusations of “cartographic aggression.” New Delhi retaliated by stamping its own map into the passports of Chinese nationals applying for Indian visas. On the surface, the consular contretemps was a trivial bit of gamesmanship. But coming just as Indians were recounting the lessons of the 1962 war, it also underscored how the border area is the only place where the outbreak of armed conflict is a realistic possibility, as well as the focus for much of India’s expansive plans for military modernization.

The Chinese threat in the border area has dominated Indian security thinking over the past few years. Consider the celebratory reception in India of the test launch last April of the Agni V, a long-range missile capable of striking Shanghai and Beijing that the Indian media quickly dubbed the “China killer” or New Delhi’s announcement this January that it will equip a follow-on missile, the Agni VI, with multiple warheads so as to have greater coverage of Chinese targets. New Delhi has also decided to station the supersonic BrahMos cruise missile in Arunachal Pradesh, the first deployment of offensive tactical missiles against China.

The border area was the site for the month-long war between the countries in 1962, as well as serious military crises in 1967 and 1987. And the chances are good that the frictions here will only intensify in the years ahead since the border dispute is not simply a matter of contested claims over real estate but is bound up with the increasingly volatile issue of Tibetan nationalism. It is no coincidence that Beijing in recent years has turned up the volume about its territorial claims on the northeastern Indian states of Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh at the same moment that the ethnic Tibetan population inside China has become more restive.

Adding to the combustible mix is the location of Tawang Monastery, a revered site in Tibetan Buddhism that is just inside the Indian side of the contested border and which is likely to play an important role in the selection of the next Dalai Lama. Noting the Sino-Indian tussle over it, a New York Times report a few years ago called Tawang “perhaps the most militarized Buddhist enclave in the world.”

Given the volatility of the Tibetan issue, one could envision without much imagination scenarios that result in a military confrontation along the frontier. One might involve the outbreak of serious unrest within Tibet, leading to a Chinese crackdown that spills into India. Beijing could bring economic or military pressure on New Delhi to clamp down on the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan exile community in northern India, setting off a dangerous spiral of misperception and miscalculation. Alternatively, the passing of the Dalai Lama, who is now 77, could spark a tumultuous search for his successor, leading China to seize Tawang so it can control the outcome.

Unfortunately, there is ample historical precedent for such scenarios. Indian support of the abortive Tibetan uprising in 1959, for example, colored Beijing’s perceptions in the lead-up to the 1962 border war. And in the mid-1980s, an isolated incident in the Sumdurong Chu Valley in Arunachal Pradesh led to a serious military stand-off in early 1987. As one of the WikiLeaks dispatches from the U.S. embassy in Beijing reported, some Chinese observers believe that policy on Tibet is even more inflexible than toward Taiwan, where Beijing at least tolerates some U.S. interference. And with memories still fresh about how ethnic unrest in Xinjiang forced President Hu to fly home earlier from the July 2009 G-8 summit in Italy, Beijing’s spending on internal security now tops even its rising outlays on defense.

Indeed, neuralgia on the Tibet issue has impelled the People’s Republic, officially an atheistic party-state, to entangle itself in deeply into the affairs of Tibetan religious institutions, including absurdly banning the current Dalai Lama from being reborn anywhere but inside China and insisting that it alone has the definitive word on the selection of his successor. It drove Beijing in 1995 to kidnap a six year-old Tibetan boy who the Dalai Lama proclaimed as the Panchen Lama, the second-ranking figure in Tibetan Buddhism. The boy’s fate remains unknown; Beijing has promoted its own candidate as the true Panchen Lama. While many Tibetans see this person as a pretender, he provides Beijing a key opening to manipulate the selection for the next Dalai Lama, since the Panchen Lama traditionally has a central part in the process.

The future direction of India’s relations with China will most likely come to mirror the present composition of U.S.-China relations. That is, cooperative impulses emanating from deepening economic engagement will moderate the likelihood of outright military hostilities. Moreover, just like in Beijing, leaders in New Delhi will continue to place priority on the imperatives of internal economic development. Added factors acting to stabilize things are the profound sense of restraint embedded in Indian strategic culture, as well as New Delhi’s realization that China continues to see the United States as its principal strategic competitor.

Yet it is clear that some fundamental geopolitical forces are at work in spurring India-China strategic frictions. Instead of being the fraternal titans that drive the Asian Century forward, as envisioned in the “Chindia” chimera, it is more likely that their relationship in the coming years will be marked by increased suspicion and rivalry.

The cross-currents affecting New Delhi’s approach toward Beijing are on display in a high-profile report issued a year ago by prominent members of the Indian foreign policy establishment. Seeking to chart out a set of basic principles to guide national security policy over the next decade, the report emphasizes that strategic independence remains “the core of India’s global engagements even today.” Yet it surprisingly had much more to say about China than about the United States. Noting that India cannot “entirely dismiss the possibility of a major military offensive” along the Himalayan border, the report argued that:

China will, for the foreseeable future, remain a significant foreign policy and security challenge for India. It is the one major power which impinges directly on India’s geopolitical space. As its economic and military capabilities expand, its power differential with India is likely to widen….

….The challenge for Indian diplomacy will be to develop a diversified network of relations with several major powers to compel China to exercise restraint in its dealings with India, while simultaneously avoiding relationships that go beyond conveying a certain threat threshold in Chinese perceptions. [Emphasis added.]

In a subsequent newspaper piece, Shyam Saran, a former foreign secretary who was involved in the report, elaborated on these themes. He argued that it would be best, at least for the time being, to avoid the encumbrances of an alliance with Washington. Yet he also acknowledged that:

Given the challenge that China’s apparently relentless rise poses to India, the pursuit of a ‘non-aligned’ policy appears unwise. The US has greater affinity and empathy with India. It supports India’s acquisition of economic and technological capabilities and has convergent concerns over Chinese hegemony.

The key question in all of this is how the U.S.-China and China-India rivalries will intersect. Much of Washington’s policy toward New Delhi over the past decade is predicated on the belief that the China-India rivalry will inevitably deepen in coming years as both countries expand in power and aspiration, causing India in turn to move into ever closer strategic collaboration with the United States. From this premise, U.S. policymakers reason that it is in America’s geopolitical interest to bolster the development of India’s power resources. Although U.S. and Indian officials are quick to deny that their quickening relationship has an anti-China motive, a former Bush administration official sums up U.S. thinking this way: “China is a central element in our effort to encourage India’s emergence as a world power. But we don’t need to talk about the containment of China. It will take care of itself as India rises.”

The visit of U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta to New Delhi last summer illustrates how the Obama administration has now resumed its predecessors’ practice of engaging the country on high-profile security initiatives. Panetta stopped in India as part of an eight-day swing through Asia designed to fill in the details about Washington’s new military buildup in the Asia-Pacific region that is plainly directed against China even if no one in Washington cares to admit it publicly. As part of the strategy, the United States will shift the bulk of its naval combat power to the Pacific in the coming years as well as deepen military and economic ties with regional allies and friends.

In an important address in New Delhi, Panetta made clear that the Obama administration sees India as a “linchpin” in this strategy. Stating that the United States “views India as a net provider of security from the Indian Ocean to Afghanistan and beyond,” Panetta proposed the formation of a long-term strategic partnership, one that featured greater Indian access to the latest U.S. military technology and a defense trade relationship that went beyond a focus on one-off transactions to include joint research and co-production efforts.

The Panetta trip, followed one month later with a visit by Deputy Defense Secretary Ashton Carter, underscores how the Obama administration is committed to organizing a regional balance of power against China and desires India’s key assistance toward that goal. New Delhi’s response to this overture will undoubtedly be halting, more than occasionally causing frustration in Washington. But over time its strategic imperatives vis-à-vis China will ineluctably draw it into a closer geopolitical affiliation with the United States.

This commentary is cross-posted on Chanakya’s Notebook. I invite you to connect with me via Facebook and Twitter.