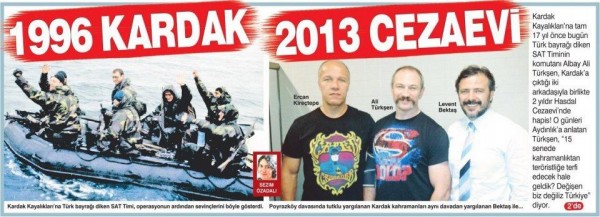

“Left: Turkish navy commandos after the landing operation on the islets of Imia/Kardak in the Aegean Sea, 1996. Right: three former navy commandos who were on the boat (left photo) in 1996. The caption reads “We were called heroes once, now they call us terrorists. It’s not us who have changed, it’s Turkey (Source: Aydınlık Newspaper)”

Turkey’s Jailed Officers

A few weeks ago, I wrote an article on Turkey’s record number of jailed journalists, citing a number of reports and statements by rights groups and international organizations that have criticized the country for arresting journalists over alleged terrorism charges. Just to make things clear for our readers, the journalists and rights activists are not the only groups that the country’s justice system goes after. In fact, Turkey is apparently scoring another record: Since 2007, hundreds, if not thousands, of retired and active officers have been arrested, forced to resign, or prosecuted, to say the least, over a number of investigations into coup plots and alleged attempts to overthrow the government by using force, membership to criminal networks and terror organizations, and espionage and racketeering.

To be sure, the military’s role in Turkey has always been one of controversy. The country has endured three military interventions in the last fifty years in 1960, 1971, and 1980. The military’s last successful attempt to shape politics in the country was in 1997 when a military-sponsored National Security Council memorandum forced the coalition government led by Necmettin Erbakan of the ultra-conservative Refah Party (the predecessor of the ruling Justice and Development party, or the AKP) to resign. It was after AKP-led reforms that the generals gradually refrained from operating in the realm of politics. In the first half of the 2000s, reforms have redrawn the boundaries of military’s playground in Ankara, successfully bringing the military under civilian control. While further reforms are needed, one thing is certain in today’s Turkey, the generals stay away from politics and one simply does not see a uniformed person making comments about politics.

But, a series of investigations into the military that started six years ago has now turned into a judicial offensive that is reshaping the military’s current and future leadership. In some cases, the investigations compromised sensitive military intelligence, pushed officers to commit suicide, and forced many to voluntarily resign out of fear of prosecution. Therefore, the trials have a significant negative impact on the country’s military organization.

Turkey’s Coup Trials

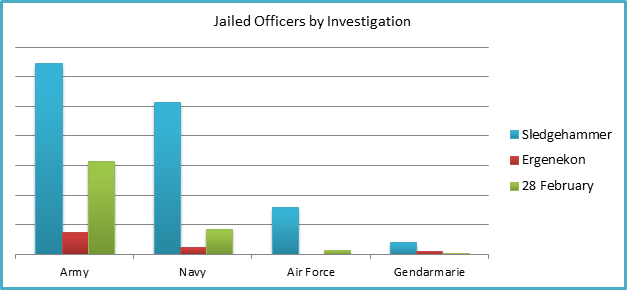

While there are several simultaneous investigations into the military, the three most important cases are the Sledgehammer Case, the Ergenekon Trials, and the February 28 Investigation. I tried to summarize each case without going into detail about their complicated legal aspects.

Operation Sledgehammer (Turkish: Balyoz Harekât Planı) is the name of a 2003 Turkish military coup plan designed by the first army leadership in Istanbul. The investigation started after an unknown source handed the daily Taraf newspaper a luggage-full of alleged military documents and operational details such as plans to bomb two Istanbul mosques and fuel tensions with Greece by shooting down a Turkish plane over the Aegean Sea. The plan, as argued by the prosecutors, was to stir up chaos in Turkey, delegitimize the newly-elected AKP government, and finally to set the stage for a military coup. Last September, an Istanbul court announced its verdict on the so-called Sledgehammer Case (Balyoz Davası). More than 300 of the 365 suspects were sentenced to prison terms. Three retired generals – Çetin Doğan (former commander of 1st Army in Istanbul, one of the four field armies of Turkish Army), İbrahim Fırtına (former air force chief) and Özden Örnek (former navy chief) were sentenced to 20 years on the grounds that their attempts were incomplete.

The investigation into the alleged Ergenekon Organization (Turkish: Ergenekon Terör Örgütü) began in June 2007 after the police discovered several hand grenades in an apartment in Istanbul. Since then, the trials have morphed into a massive investigation that consists of several simultaneous legal cases into clandestine networks, terror organizations, coup plans, bombings, kidnappings and disappearances as well as other charges related to supporting and financing terrorism. Tens of former and active members of the Turkish military, academics, journalists, businessmen, students, rights activists, removed doctors such as Mehmet Haberal, lawyers and many others are currently behind bars. More than 700 defendants, most of whom have been in prison since 2007, are expecting to hear the court’s ruling. Last Tuesday, the prosecutors finally asked for aggravated life imprisonment for 64 suspects including the former Chief of General Staff General İlker Başbuğ, General Nusret Taşdeler, retired generals Hasan Iğsız, Hurşit Tolon and Şener Eruygur, the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) lawmakers Mustafa Balbay, Mehmet Haberal and Sinan Aygün, former leader of Workers’ Party Doğu Perinçek, as well as journalists Tuncay Özkan and Mustafa Balbay (who started his fifth year in prison in early March) on accusations of attempting to overthrow the government by using force.

The latest addition is the 28 February Investigation (Turkish: 28 Şubat Soruşturması). As the name suggests, the investigation is into the February 1997 National Security Council Memorandum (jointly issued by the Turkish Military leadership and the President, signed and approved of by the prime minister) that eventually led to the resignation of Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan of the ultra-conservative Refah Party, and to the fall of the coalition government led by Refah. The police have arrested more than 80 high-ranking officers as part of the investigation over the last six months. In addition to the three processes outlined above, tens of people are prosecuted in other legal cases such as the Military Espionage and Racketeering Trial. While the validity of reports in the media is always disputable, some newspapers claim that the police have identified more than 2500. New waves of arrest may start soon.

Turkey’s Jailed Officers

Quite a number of people hold that in the end, these trials are a good thing – despite their shortcomings, they ended the military’s power over politics and strengthened democracy and rule of law in the country. Yet, many more see the trials as part of what can be called “Turkey’s Great Purge,” where those who are in power are simply subduing political opponents and perceived threats by using the judiciary as a weapon of political warfare. To many critics, the trials have now spiraled out of control and turned into a manhunt to reshape Turkey’s military leadership.

While there is a wide range of arguments thrown in by both pros and cons of the trials, an often sidelined aspect has been the actual impact these trails have had over Turkish military’s operational capabilities and discipline. To say the least, the number of jailed officers in the country has now reached critical levels. While tens of officers are being prosecuted or jailed, many others choose to resign voluntarily either to protest the ongoing investigations or because they are worried about their future, and they are right to do so. Many mid-ranking officers are facing long prison terms only because they were ordered to attend a seminar where a four star general emphasized his disappointment with some of government actions. A retired air force officer recently told me that young officers “try to avoid seminars and conferences by getting a doctor’s note or finding another activity” because they fear that they may end up in prison one day. Last January, CNNTurk reported that more than 100 fighter pilots requested their resignation from the Turkish Air Force. Also in January, Admiral Nusret Güner, then-number two of Turkish navy, resigned as an apparent reaction to the ongoing investigations into the Turkish navy over alleged espionage networks, prostitution rings and coup plots to overthrow the government.

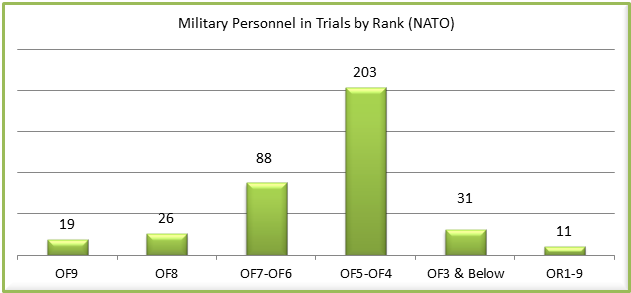

According to the ministry of defense, more than 400 officers are currently investigated or jailed as part of the above-mentioned cases. Broken down by rank, a total of 64 generals and admirals, 273 officers, 60 non-commissioned officers, four specialists and three civilians are either under investigation or in jail. Despite its relatively small size, the Turkish navy seems to have received the heaviest blow with 112 of its officers currently behind bars. Interestingly, of the 112 jailed officers, 66 are in the rank of colonel. If they weren’t jailed or prosecuted, most of these officers would be making up the top echelons of naval forces. After navy’s Admiral Güner (former Commander of the Fleet) resinged in January, the country’s naval force has only one senior officer left in the rank of Admiral: Admiral Murat Bilgel who’s also the current chief of the Navy. However, he is set to retire this August and his tenure may or may not be extended next August. Moreover, there are no senior officers in the rank of vice admiral who can be promoted to the rank of admiral in 2013 or 2014. More importantly, of the 47 admirals in the navy, 12 are currently behind bars among them fleet commanders.

Military’s Future Behind Bars

The majority of officers who received prison terms are coming from the ranks that would shape the military’s future leadership. It is interesting that the trials are taking their toll over the core of the military’s commanding ranks – colonels and lieutenant colonels. If they had not been arrested, forced to retire or fired, these officers would be leading the military starting in 2014 – the same year Prime Minister Erdogan is hoping to run for his fourth term in office, or become Turkey’s first president with full executive powers to hold the title of commander-in-chief.

One of AKP’s most applauded reforms was to bring the military under civilian control. Yet, as an aspiring regional and global player and a NATO member in a troubled region and with the longest land border with Syria to the South and bordering Iran and Iraq to the East, controlling the only exit for Russia’s powerful Black Sea Fleet, the country must maintain a functioning military organization. The AKP leadership has ambitious plans such as increasing Turkey’s military involvement in overseas peace operations and making the country a long-term development aid provider in the near future. The country’s “global player” ambitions are, however, unlikely to materialize with a decaying military force. Turkey’s success is essentially linked to the country’s ability to ensure the rule of law and democracy while sustaining a professional military force that has allegiance to the constitution and law, not to an ideology enforced upon it by the ruling elite.

Note: please refer to “Ranks of NATO Armies and Officers”.