Image: Australian Broadcasting Corporation

The vice grip of prolonged violence suffocating Syria is sending the humanitarian situation there careening towards the fading lights of a blackout. With a death toll looming somewhere between 70-90,000 and a refugee population of over a million in two years time, international intervention to this point has been largely limited to food aid and armored vehicle shipments while foreign leaders grapple with the implications of sending opposition forces lethal armaments. As the G8’s Foreign Ministers meeting convenes in London next week, Britain’s hosting chief diplomat, William Hague, proposes an agenda he hoped would favor conflict prevention that is now making room for crisis alleviation.

The U.K. holds this year’s G8* presidency and its leadership is keen to make the most of the post. In announcing the Ministers meeting last year, Hague was primed to comment on the ground he wished to cover. The official statement released by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in November outlined an ambitious field of diplomatic concerns. Those early bullet points looked to Middle East regional stability and an examination of the group’s role in facilitating and promoting economic development and open governance in the Arab Spring states. He linked these elements as building blocks of conflict avoidance. They are not without an existing framework from which Hague wants to work – the Deauville Partnership.

The marina-laced seaside resort town of Deauville, France, lays in stark contrast to the bloodied upheaval witnessed by the flush of states comprising the Arab Spring. Their connective thread exists by way of a G8 meeting hosted in this oasis of the French northwest in May 2011. The meeting was a wisp shy of six months past Tunisia’s initial flashpoint – the self-immolation of Mohammed Bouazizi in an open market in Sidi Bouzid – and the initiative born from it aimed to build trade and investment relationships between these larger economies and the burgeoning governments of the Spring. The diplomatic designs of such a partnership were probably fixed on creating incentives for democratic transition and renewed alliances with the West early on in a period of transformative political fragility.

Beyond assessing the state of Deauville, preliminary discussions on Somalia ahead of a summit on the state in May and the eradication of rape as a weapon of war in conflict zones are directly identified in the agenda. Hague used the ensuing months, and the agenda progress reports released during that time, to highlight and evolve these points – taking on a prominent role in a February meeting with Spring state representatives in Rome to advance the tenets of Deauville as well as a high-profile trip to the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda at the end of March with U.N. Human Rights Commission Ambassador and actor Angelina Jolie to highlight gender-based violence and define the issue as a personal priority for his counterparts in London come Wednesday.

Image: CNN

Although Syria did not make the initial round of meeting objectives by name, Hague left room for addressing the pressing security issues happening in time with the ministers meeting. And just as his work over the past four months has drawn attention to the other topical discussions he’ll facilitate next week, Syria has increasingly appeared on Hague’s public radar.

This increased prominence is no accident. Since November, Prime Minister David Cameron has considerably ramped up Britain’s diplomatic profile around Syria. Formally identifying Syrian rebel partners, drawing public attention to increases in aid, facilitating conferences on developing a post-Assad transition and offering much clearer language on intervention options than any of the other G8 states all feature as part of the prime minister’s emerging scheme. His foreign minister, a long-standing ally, has used his podium to plainly deliver Cameron’s message.

A converted country estate in the southeastern English county of Sussex serves as a conference center for the Foreign and Commonwealth Office outside of London. It housed a two-day meeting on the Syrian crisis at the start of the year, drawing a collection of country experts from across the globe and leaders of the moderate Syrian opposition to brainstorm scenarios for a post-Assad transition. While not present, Hague’s expressed aim for the meeting was to outline possible plans for what he and Cameron see as Assad’s “inevitable” departure from office. Orchestrating the meeting was a less-than-subtle suggestion that the shape and look of the New Syria was somehow entwined with British influence and assumed the impending demise of its standing, if withered, government.

In March, Hague made his most forceful comments on the crisis by taking aim at an EU ban on the shipment of lethal-force arms to the Syrian opposition, citing the immediacy and magnitude of the humanitarian deterioration there as cause to leave all intervention mechanisms available for use. Britain currently stands in line with the EU embargo, offering food and reinforced vehicles, but this solidarity could be short-lived. Hague has not minced words in expressing the possibility that the U.K. may subvert the ban and send lethal armaments to specific groups within the opposition movement anyway.

Hague is no stranger to rustling feathers with Brussels. He is a long-standing eurosceptic and while his pronouncements on Syria are outlined for him by the prime minister, one wonders if this colorful diplomat relishes the opportunity to be the voice of a move viewed as a disassociation from the continent and, by extension, the U.K.’s often conflicted European identity.

If Hague plans to open a discussion on Syria at the Ministers meeting with suggestions that all options be on the proverbial table, the reply may take the form of a pronounced ringing in his ears — a potent mix of hesitant silence from some and resounding rejection from others. A notable member of the cricket gallery will likely be new U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry. The Obama administration has avoided suggestions that any Syrian endgame could go as far as to involve a “boots on the ground” strategy and hasn’t wished to draw heightened attention to CIA efforts in siphoning arms into Syria and facilitating training of opposition groups with Turkey. Another will be French foreign minister Laurent Fabius who, until recently, was aligned with the U.K.’s overtures. Late last week Fabius released a position reversal requesting more time in determining its interest in sending weapons to Syrian opposition forces.

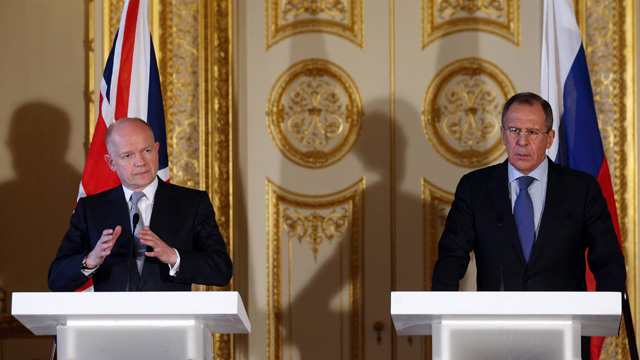

The EU’s British foreign minister, Catherine Ashton, will find herself wedged between her official and national identities when she attends — likely with her hands tied by the former. The most vocal opponent of the British position is Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov, who calls such a move illegal in the realm of international law and in overt disregard for the European Union embargo. This comes despite a one-on-one meeting with Hague on Syrian goals as part of the first U.K.-Russian Strategic Dialogues last month.

So, an impasse at the outset. But the Ministers meeting offers time to push the conversation further. Maybe. Such conferences suffer an intrinsic flaw in their general structure — time constraints. When the pleasantries are through and the doors to the public and press are closed, two days is a brutally short amount of time to volley points of cohesion and division among power states on even a single issue let alone spread their energies across a field of many subjects. Subjects which, in this case, are complex and deserving of more than a few hours of chatter before the day’s diary moves everyone along to the next. Certainly, no minister/secretary stands alone and they will descend on London with advisory teams in-tow and each will have position points on the ready and a backlog of exchanges shared in pre-meeting conversations, but preparatory work is no substitute for a thorough negotiation once everyone’s around the table.

Image: The Guardian (UK)

The ministers meeting is not a playground for breaking new policy ground. The point isn’t to go charging back to the offices of respective executive leaderships with blueprints for proactive coalitions of the willing. As an exercise in high-level diplomacy, the language at the end of these gatherings is largely littered with reaffirmations of existing alliances and generalized pledges to work together on reaching common ground in areas of discord. What else can truly be expected when hosting states want to tackle so much? Last year’s U.S.-lead ministers meeting covered transitions in the Middle East and North Africa, Middle East peace, Iran, North Korea, Afghanistan, Africa, terrorism, maritime security, and transnational organized crime. In two days.

Britain’s managed to back itself into a corner over the question of a future Syria, having taken on such a pronounced role in the exploratory consideration of a solution and open-ended language about where its capacity for aid begins and ends. The Syrian opposition liaison to London publicly identified the U.K. as the best remaining hope for external intervention. It’s politically treacherous territory to inhabit. The British constituency is largely wary of over involvement, fatigued by what is viewed as the U.K.’s habit of assuming huge burdens in the security affairs of other states. Following its experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq, intervention arguments, even when tinged by a visible display of human suffering like that witnessed in Syria, are met with an audible shuffling backward.

It is unlikely that the after action report on next week’s meeting will see a syncing of the collective G8 and EU message on Syria. But with so much political exposure and personal investment in a home court discussion among an audience of peers, Hague needs to produce a statement fuller in body than “my colleagues and I agree that we want to see a peaceful end to the situation plaguing Syria.” Well, of course. Perhaps the best-case scenario is a genuinely thorough trade of constructive ideas on how each state’s respective offerings can be webbed together to create workable approaches to helping Syria forward. He’s got a lot of other ground to cover. Let’s hope the time clock is forgiving, because a million displaced Syrians hanging in the air are expecting more from the U.K.

*The G8, long-form “Great Eight,” is comprised of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the U.S. and the U.K.