If you have not seen it, you ought to check out the new Chilean movie NO. A fictionalized account of the campaign to remove Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet through a plebiscite, it was one of this year’s Oscar nominees for Best Foreign Language Film. You should be aware, however, that it does not tell the entire story.

When Pinochet promulgated a constitution in 1980, after he had already been ruling the country for seven years, the document provided for a plebiscite to be held in 1988. It would be a simple affair; people could vote, YES or NO, on whether Pinochet should continue as president for yet another eight years. When the time came, the legal opposition parties combined to organize the No Campaign (La Campaña del NO). Under international pressure, the general permitted the YES and NO campaigns fifteen minutes of TV time every night for a month prior to the vote. In the movie, the NO organizers turn to a professional advertising executive who develops a series of nearly absurdist TV commercials that hawk democracy and justice as if they were soft drinks. (“¡Chile, la alegría ya viene!” [“Chile, happiness is on the way!”]) But, hey, you can’t argue with success. The No Campaign’s 15-minute slot reportedly became the highest-rated program in Chilean television. (Spoiler alert: Pinochet loses.)

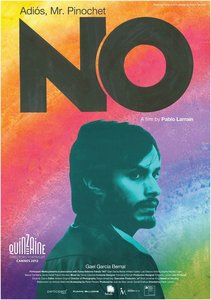

Mexican actor Gael García Bernal portrays a Chilean advertising executive with a mission in Pablo Larraín’s NO. (Photo: wikimedia.org)

While a fictionalized account (the movie’s main character, advertising executive René Saavedra, did not even exist), people familiar with the campaign seem to agree that the film has caught the spirit. Moreover, about 30 percent of the movie consists of actual archival footage, including news broadcasts (how many movies can credit Augusto Pinochet as “Himself”?) and the actual commercials. The rest of the movie was shot with old, reconstructed video cameras so that it would blend in with the archival footage.

People connected with the campaign have complained, however. The movie is solely about the television advertising and therefore fails to acknowledge the real core of the campaign, a massive grassroots effort to register 7.5 million jaded Chileans who were convinced that their vote would not matter. This, no doubt, rates a movie of its own. However, there was yet a third side to the story. The movie hints at it toward the end, but it was visible to neither television viewers nor grassroots activists at the time.

Pinochet’s Contingency Plan: “I’m not leaving, no matter what.”

Jaded Chileans, we now know, should not have been totally pessimistic about the outcome of the referendum, but clearly they were right to be skeptical. Pinochet’s original plan did not include losing as an option.

The George Washington University’s National Security Archive has assembled a number of declassified U.S. government documents that give a glimpse into the activities behind the scenes in the Chilean government. The U.S. ambassador, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) had excellent contacts within the government, and it appears that at least some of those contacts were fairly free with their information. For weeks Washington received reports about the development of Pinochet’s three-point contingency plan: (1) If the government won the referendum, it would accept the results, pat itself on the back, and continue as before; (2) if the government lost narrowly, it would falsify the numbers, claim that it had won, pat itself on the back, and continue as before; and (3) if the government lost by a substantial margin, it would foment violence on a massive scale, blame the violence on the opposition, and use it as justification to declare a national state of emergency, or in other words, martial law. As the ambassador put it:

Since we know that Pinochet’s closest advisors now realize he is likely to lose, we believe the third option is the one most likely to be put into effect with probable substantial loss of life.

The DIA provided a bit more detail:

Close supporters of President Pinochet are said to have contingency plans to derail the plebiscite by encouraging and staging acts of violence. They hope that such violence will elicit further reprisals by the radical opposition and begin a cycle of rioting and disorder. The plans call for government security forces to intervene forcefully and, citing damage to the electoral process and balloting facilities, to declare a state of emergency. At that point, the elections would be suspended, declared invalid, and postponed indefinitely.

The scenario harkens back to the aftermath of the 1973 coup, when Pinochet’s newly installed junta restored public order — or its notion of public order — by rounding up political opponents by the thousands for torture and execution. One of the more sober TV segments in the NO Campaign presents a series of women quietly listing the names of relatives and the dates on which they had “disappeared” without a word.

The Reagan administration had already come to the conclusion that the Chilean dictatorship was undesirable, if only because Pinochet’s intransigence was radicalizing the left and marginalizing the center. To its credit, the administration issued instructions to its diplomats, intelligence officers, and military attachés to impress upon their Chilean counterparts that carrying out this plan would seriously damage relations with the United States and destroy Chile’s “reputation” in the world. Translated out of diplomatic speak, that is a fairly stark message. The administration asked the British to convey the message as well. Surely, many key members of the Chilean political elite took note. The pro-Pinochet press was already referring to Ambassador Harry Barnes as “Dirty Harry” for his open support of the registration drive.

So, What Happened?

Turnout of registered voters on October 5, 1988, was an incredible 97 percent. Early in the evening, the authorities issued a partial result that placed the YES vote well ahead. This was completely fraudulent. As more results came in from the polling stations, the authorities stopped issuing partial results. The final tabulation placed NO ahead by more than 10 percentage points, 54.7 percent to 43 percent. According to the plan, Pinochet supporters were to be called out onto the streets to celebrate the “victory,” anyway. Characters in the movie note at one point that the police had disappeared from the streets. Although they do not discuss it further, this would be an ominous sign, presumably opening the way for “unofficial” mobs to start a riot, but that did not happen. The plan was apparently frustrated when the national police (Carabineros) unexpectedly refused to lift an election-day ban on street demonstrations, even for Pinochet supporters.

Behind the scenes, Pinochet was reportedly “nearly apoplectic.” He ordered the top generals who made up the junta to meet him at the Moneda Palace at 1:00 a.m., and he had the papers prepared with which to grant himself emergency powers.

Near the end of the movie, TV news footage shows the officers entering the palace. General Fernando Matthei, the commander of the air force, turns to a reporter and comments that, obviously, the No Campaign had won. He does not appear particularly happy about it, but he says it. The characters in the movie take this to mean that the generals are abandoning the dictator. That is precisely what happened. Pinochet presented them with the emergency decree and spoke of ordering troops into the city. One by one, starting with General Matthei, they said, “No.”

Who Stopped the Violence?

As noted above, members of the Chilean political elite had surely taken note of the message emanating from the United States, but how much of an impact did it have? It is easy to conclude that the Americans saved Chile for democracy, but life is rarely that straightforward. Cleary, the message had not had much of an effect on Pinochet himself.

The generals were, no doubt, torn by multiple considerations in a scenario not unlike that which occurred in Egypt just two years ago. Obviously they had no strong ideological objection to the junta of which they were members, but they probably also assumed that it had a substantial amount of popular support for the stability and relative prosperity that it had brought the country. That assumption had now been shaken by the plebiscite results. Moreover, it was no longer 1973; they could not tell themselves that they were saving the country from growing violence, political paralysis, and economic crisis, which, regardless of one’s feelings about Salvador Allende or the coup, were part of the reality of that time. And although the YES Campaign repeatedly likened the opposition to Marxist guerrillas, Christian Democrat Patricio Aylwin, the leader of the No Campaign, was no Che Guevara. The generals were the ones being asked to start the violence—conceivably a civil war—and for no better reason than the keep the 73-year-old Pinochet in office for eight more years. Finally, they had to take the U.S. threat seriously. After all, just two years earlier the Reagan administration had helped nudge Ferdinand Marcos out of the Philippines and Jean-Claude Duvalier out of Haiti when their people mobilized against them.

So, the answer to the question, “Who stopped the violence?” is a complex one. It was the people who made the absurdist TV commercials; it was the people who canvassed the neighborhoods and convinced 7.5 million potential voters to register; it was the people who went out and voted even when they had every reason to believe their votes would not count; it was the foreign governments, diplomats, and officers who warned their Chilean counterparts of the negative consequences they could expect if a NO vote was frustrated; and it was a small set of authoritarian generals who still had enough integrity to call off a slaughter that even they could not justify. It is difficult to assign relative weight to all the items on the list (although the TV commercials would probably not be at the top), but it is hard to see the same outcome occurring if any of the items had been taken away.