A post last month argued that President Obama was fast approaching a defining moment for his foreign policy in view of the mounting evidence that the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria used sarin, a lethal nerve gas, in violation of Mr. Obama’s numerous warnings not to do so. The day of reckoning has now arrived and it reflects badly on the president.

A post last month argued that President Obama was fast approaching a defining moment for his foreign policy in view of the mounting evidence that the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria used sarin, a lethal nerve gas, in violation of Mr. Obama’s numerous warnings not to do so. The day of reckoning has now arrived and it reflects badly on the president.

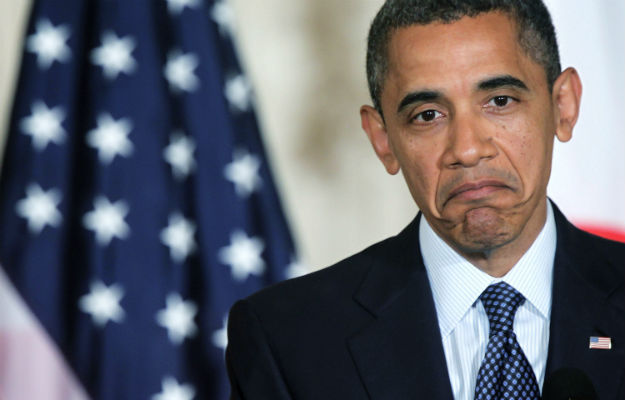

Speaking at a White House press conference last week with Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Obama made plain that he is now unwilling to enforce the red line he so recently staked out in Syria. Speaking of the increasingly complex civil war there, he stated,

This is … an international problem….It’s not going to be something that the United States does by itself. And I don’t think anybody in the region would think that U.S. unilateral actions … would bring about a better outcome.

Although Mr. Obama was careful to preserve the option of joining in a collective military response, his keen desire to avoid strategic entanglements in the Middle East was evident enough. Ever since the White House reluctantly acknowledged (here and here) last month the likelihood of chemical weapons use, he has given every indication of a man looking for a way out of his pledge. Hence, his current insistence that before he acts a U.N. investigative team must provide conclusive proof, even though Damascus continues to stymie that effort and Russian and Chinese diplomatic backing of the al-Assad regime blocks meaningful action in the U.N. Security Council.

Indeed, Moscow has been expanding its naval presence in the eastern Mediterranean in a way that appears aimed at deterring Western intervention in Syria as well as shipping to Damascus advanced air-defense and anti-ship systems that are meant to keep outsiders away. Vladimir Putin’s disdain for John F. Kerry earlier this month is also instructive. The U.S. Secretary of State traveled to Moscow seeking the Kremlin’s help for a Syria peace plan. But the Russian president kept Kerry waiting three hours before granting him an audience, fiddled with his pen while his guest spoke and then avoided the subject of Syria altogether in his own public remarks.

And the lawyerly caveats that Mr. Obama hastily attached to his red line last month were hardly signals of steely resolve. These include distinguishing “localized” incidents from “systematic” chemical attacks as well as stressing the need to verify the “chain of custody” for war-zone evidence – a requirement the New York Times characterized as “turning the matter into an international ‘CSI’ case.” Ditto for the Hamlet-like ponderings, as when Obama asserted in an interview earlier this year: “How do I weigh tens of thousands who’ve been killed in Syria versus the tens of thousands who are currently being killed in the Congo?” And as we have now learned, the presidential red line was casually drawn in the first place.

Perhaps, as the administration defenders argue, the better part of strategic wisdom is steering clear of Syria’s metastasizing chaos, which a senior U.S. official describes as “one giant Florida sink hole.” (For useful background on the escalating mess, see here, here and here.) There are, to be sure, no easy judgment calls. But Mr. Obama should also realize there are significant downsides to backing away from a presidential red line:

The first and foremost cost is to his credibility vis-à-vis Iran’s atomic ambitions. The president regularly insists that he is prepared, if necessary, to resort to military means to stop Iran’s nuclear weapons program. “I don’t bluff” is how he memorably phrased his threat a year ago, and Vice President Joe Biden recently reiterated this line. And just last week a top State Department official told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that:

We will not allow Iran to obtain a nuclear weapon, and there should be no doubt that the United States will use all elements of American power to achieve that objective.

The Obama administration’s warnings toward Iran has always had the air of unreality, given the president’s widely-broadcast determination to wind down U.S. military involvement in the Greater Middle East as well as his rhetoric about the overriding urgency of focusing on “nation building at home.” But Mr. Obama has now given officials in Tehran even more reason to discount the tough talk he regularly directs their way.

The climb down also further diminishes already waning U.S. influence in the Middle East. The president entered the White House determined to restore America’s standing in the region. Four years ago, he traveled to Cairo to proclaim a “new beginning” between the United States and the Muslim world, and two years ago he announced “a new chapter” in U.S.-Arab relations that would constructively engage the political forces emerging from the Arab Spring. Yet as one expert sympathetic to the administration notes, U.S. street cred has now hit an all-time low in the Middle East. The hasty exit from Iraq that Mr. Obama trumpets to domestic audiences has resulted in the marked loss of U.S. clout in Baghdad while Iran’s influence expands there (here and here). To be sure, navigating the complex currents unleashed by the Arab Spring would prove tricky regardless of who is in charge in Washington. But Mr. Obama’s promised “new chapter” has so far fallen victim to bureaucratic inertia and caution.

The retreat from the Syrian red line only reinforces widespread regional perceptions that the administration prefers to sit on the sidelines. As the Washington Post editorial board argued a few weeks ago: “If Mr. Obama waffles or retreats on the one clear red line he drew, U.S. credibility across the region will be severely damaged.” And the Wall Street Journal now reports that Washington’s closest allies in the Arab world are trouping to the White House to implore Obama to show more backbone on Syria.

A final cost is to Obama’s goal of burnishing America’s moral reputation. Just a year ago, the president went to the U.S. Holocaust Museum to declare:

It’s a bitter truth — too often, the world has failed to prevent the killing of innocents on a massive scale. And we are haunted by the atrocities that we did not stop and the lives we did not save.

Emphasizing the theme of “never again,” he announced the establishment of a new Atrocities Prevention Board that would institutionalize Washington’s focus on preventing and responding to mass atrocities. Yet with at least 70,000 dead in the Syrian civil war and the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees calling the conflict “the worst humanitarian crisis the world has faced since the end of the Cold War,” many are now wondering whether the president’s fine words amounted to mere preening (here, here and here).

Worse still is the huge disjunction between the president’s “never again” commitment last year and the “see no evil” approach that the administration currently takes on the question of chemical weapons use. One Obama adviser justified inaction to the New York Times by saying, “If [Assad] drops sarin on his own people, what’s that got to do with us?” And at a recent State Department meeting, according to another media account, “No one wanted to say that Assad had crossed the line, because no one wants to deal with it” – a way of policymaking that harkens back to the Clinton administration’s studied avoidance of using the word “genocide” to characterize ethnic cleansing in Rwanda and Bosnia in the early 1990s for fear of being obligated to act. Ironically, Samantha Power, the White House official who runs the Atrocities Prevention Board, excoriated these moral derelictions in her 2002 book, A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide.

This commentary is cross-posted on Monsters Abroad. I invite you to connect with me via Facebook and Twitter.