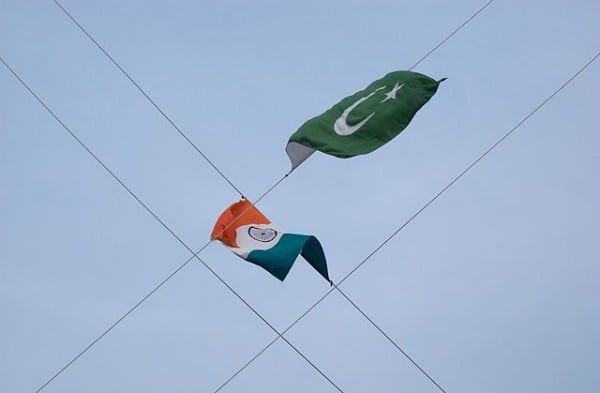

Nawaz Sharif’s return to the helm in Islamabad is sparking optimism that a more stable and constructive India-Pakistan relationship is in the offing. But South Asia is a rough-and-tumble neighborhood that regularly eviscerates the best of intentions. Indeed, given the potent brew of pernicious forces acting on bilateral affairs – contiguous but bitterly contested territory, sharp historical animosities, internal frailties vulnerable to outside exploitation, and conflicting national identities – the real wonder is why outright conflict isn’t even more prevalent.

Much has been made of the precedent Sharif set during his last stint as prime minister, when he hosted a landmark summit meeting in Lahore in early 1999 with his then Indian counterpart, Atal Bihari Vajpayee. The resulting Lahore process gave rise to hopes that a fundamentally new era in bilateral affairs was at hand, though it quickly expired when the Kargil mini-war broke out a few months later. But Sharif has now resurrected its spirit, calling the Lahore process “the roadmap that I have for improvement of relations between Pakistan and India.”

Less noticed but worth noting how Punjab province, Sharif’s political base, stands to benefit from increased trade ties with India. This is particularly so for the Punjab-dominated textiles sector that is the country’s largest manufacturing industry. It’s also relevant that his younger brother, Shahbaz Sharif, the province’s chief minister, effusively suggested the creation of free trade zones last year aimed at fostering bilateral exchange and the opening up of supply-chain links between the port city of Karachi and the Indian states of Rajasthan and Punjab. He also proposed establishing a common market along the lines of the European Union – something that Manmohan Singh, the current Indian prime minister, has also famously advocated – and declared that the two countries should now concentrate on waging “a war of economic competition and excellence.”

Pakistan’s powerful military establishment, with its praetorian instincts and deep-rooted antipathies toward New Delhi, has always been wary of better ties with India. But it seems to have concluded, at least for now, that the country’s internal situation is so parlous that economic engagement with the arch-rival is a necessity. General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, the army chief who has maintained a hard line vis-à-vis New Delhi in the past, spoke last year of the need for “peaceful co-existence” with India and stated that his country “can’t keep spending on defense alone and forget about the development.”

Across the border, Mr. Singh has pledged to work with Sharif to chart “a new course” in bilateral affairs, and a new public opinion poll shows that a strong majority of Indians support moves to make peace with Pakistan.

And so following the disruption earlier this year caused by border skirmishes in the disputed Kashmir region, the trajectory of India-Pakistan relations appears ready to swing upwards, driven by deeper economic partnership. If enhanced trade ties were to take hold between South Asia’s largest economies, they would produce significant commercial and (eventually) security dividends for both countries and indeed the entire region. According to a slew of recent studies (good examples here, here and here), a more liberalized trade regime would increase bilateral exchange as much as 20 times above current figures, along with boosting general prosperity in both countries. A report last year by the Confederation of Indian Industries, for instance, found that cross-border trade could easily quadruple in just a few years if both governments moved to increase economic linkages.

Beyond their commercial value, stronger trade links would act as a diplomatic “force multiplier,” adding more ballast to the bilateral equation by creating a larger stake in productive interactions and lessening the likelihood that momentary frictions will disrupt the overall relationship. They also would have the benefit of strengthening Pakistan’s civil society vis-à-vis an overbearing military leadership, as well as empowering the country’s liberal-minded elements to combat the rising swell of religious extremism and political violence.

Prime Minister Sharif could quickly get the ball rolling by making good on Islamabad’s commitment to extend “most favored nation” status to India, thus reciprocating the designation India conferred upon Pakistan decades ago. Islamabad has reportedly refrained from doing this because of fears that Pakistani businesses would be overwhelmed by cheaper Indian goods. But these businesses have already weathered the commercial competition brought about by the 2006 free trade agreement with China.

Likewise, Sharif should commit to fulfilling in short order Islamabad’s promise to whittle down significantly the long “negative list” of goods that are not permitted to be imported from India. Lastly, he would do well to propose setting up a bi-national commission of distinguished business leaders to develop recommendations about expanding cross-border trade and transportation links. This would accentuate the cooperative stirrings on both sides as well as generate bold ideas and valuable political cover that could never be delivered by risk-averse bureaucrats.

But given the volatile nature of bilateral relations, Messrs. Singh and Sharif would be wise to realize that they face a very brief window of opportunity. The first constraint is leadership torpor in New Delhi. Despite having notched an impressive electoral triumph of his own four years ago, Mr. Singh has been all but a lame duck for most of his second term. Last year, Time magazine labeled him “The Underachiever” while The Economist likened him to an aging Leonid Brezhnev; India Today last month called him “Dr. Dolittle.”

Singh has long been a dogged champion of building durable relations with Islamabad. Under his watch, an intensive back-channel peace process took place in 2004-07 before petering out due to Pervez Musharraf’s troubles at home. Following the horrific November 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai, he moved quickly – much too soon in the estimation of many New Delhi elites – to repair relations with Pakistan (see here and here for background). And the New York Times recently commended him for a “sensible, workmanlike effort over the past year to improve relations between the two nuclear rivals.”

But Singh’s efforts have always been handicapped by resistance within a Cabinet of which in any case he is only nominally in charge. And even if he were able to muster more political capital than he possesses these days, the approach of parliamentary elections (due within a year, but perhaps occurring sooner) will further distract leadership attention in New Delhi away from the bilateral agenda.

The second constraint is even more serious, for it springs from the core animosities that have long deformed the India-Pakistan relationship. New Delhi and Islamabad regard Afghanistan as a key theater of their strategic rivalry. As the United States and its NATO allies complete their departure from the country in the coming year, a sharp security competition is very likely to erupt, especially if the situation deteriorates into a new civil war that has regional powers scrambling for influence. Kabul’s renewed overtures to New Delhi, including Hamid Karzai’s presentation of a wish list of military equipment during his visit to India two weeks ago, is a foretaste of this competitive dynamic. So, too, is New Delhi’s recent announcement of a strategic partnership with Tehran and Kabul, including its $100 million investment in a project to connect the Iranian port of Chabahar on the Arabian Sea to landlocked Afghanistan.

The skies are once again opening up in bilateral affairs, though Singh and Sharif would be foolish to think that storm clouds aren’t on the horizon. They would do well to lock in whatever diplomatic and economic gains they can while there still is time.

This commentary is cross-posted on Chanakya’s Notebook. I invite you to connect with me via Facebook and Twitter.